Satan's Rhapsody

"When youth is bought at the price of love, is the bargain worth the soul?"

Plot

In this haunting Faustian tale, an elderly countess, weary of her age and loneliness, makes a desperate pact with Mephisto to regain her youth and beauty. The devil grants her wish, transforming her into a stunning young woman, but with one cruel condition: she must never experience true love or lose her soul to damnation. Reborn as the captivating Alba Doria, she moves through high society, where two brothers, the noble Sergio and the passionate Tristano, both fall deeply in love with her. As she struggles to maintain her emotional distance while being drawn to both men, Alba faces an impossible choice between eternal youth without love or risking damnation for the chance at genuine connection. The film culminates in a tragic resolution that explores the devastating consequences of bargains with darkness and the eternal conflict between desire and damnation.

About the Production

Filmed during the height of World War I, which created significant production challenges including material shortages and restricted movement. The film utilized elaborate Art Nouveau-inspired sets and costumes designed to showcase Lyda Borelli's ethereal presence. Special effects techniques of the era, including multiple exposures and dissolves, were employed to create the supernatural transformation sequences. The production faced wartime censorship issues due to its occult themes, requiring several scenes to be reshot or modified.

Historical Background

Released in February 1917, 'Satan's Rhapsody' emerged during one of the darkest periods of World War I, when Italy was experiencing massive casualties and social upheaval. The film's themes of bargaining with dark forces for youth and beauty resonated deeply with a society grappling with mortality and loss. Italian cinema of this period, despite wartime restrictions, was experiencing its golden age, with films like this representing the pinnacle of artistic achievement. The diva film genre, of which this is a supreme example, reflected changing attitudes toward women's roles in society, with female characters exercising agency and power, albeit often through supernatural means. The film's production occurred as the Italian film industry was transitioning from its early dominance of the international market to a more insular period, making 'Satan's Rhapsody' one of the last great international-style Italian productions before the war's end.

Why This Film Matters

'Satan's Rhapsody' represents the apex of the Italian diva film genre, a uniquely Italian contribution to world cinema that celebrated the power and mystery of the female protagonist. The film established visual and narrative conventions that would influence Gothic cinema for decades, particularly in its portrayal of supernatural bargains and the price of vanity. Lyda Borelli's performance created an archetype of the mysterious, tormented woman that would echo through films from German Expressionism to American film noir. The film's exploration of the Faust legend through a female perspective offered a fresh interpretation of the classic tale, influencing subsequent adaptations and gender-swapped retellings. Its rediscovery and restoration in the 1990s sparked renewed scholarly interest in Italian silent cinema and led to a reevaluation of the artistic merits of the diva film genre, which had been previously dismissed as melodramatic.

Making Of

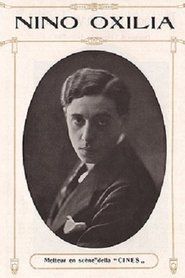

The production of 'Satan's Rhapsody' was marked by the extraordinary collaboration between director Nino Oxilia and star Lyda Borelli, who had previously worked together on 'The Fatal Kiss' (1916). Oxilia, a man of letters as well as cinema, brought his poetic sensibility to the film's visual language, creating dreamlike sequences that pushed the boundaries of silent film storytelling. Borelli, known for her intense and stylized acting method, worked closely with Oxilia to develop a performance that blended theatrical gesture with cinematic subtlety. The film's most technically challenging sequence involved the transformation of the elderly countess into the young Alba, which required days of preparation and multiple camera setups. The wartime conditions meant that the production had to work with limited resources, leading to creative solutions for special effects and set design. Tragically, Oxilia was killed in action shortly after the film's completion, making 'Satan's Rhapsody' his final artistic testament.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Alberto Chentrens and Giovanni Tomatis was revolutionary for its time, employing innovative lighting techniques to create an otherworldly atmosphere. The film made extensive use of chiaroscuro effects to emphasize the dual nature of the protagonist's existence between youth and age, good and evil. Special attention was paid to lighting Lyda Borelli to enhance her ethereal quality, using soft focus and backlighting to create a halo effect in key scenes. The transformation sequence utilized multiple exposures and careful editing to achieve a seamless metamorphosis that was technically remarkable for 1917. The film's visual style drew from Art Nouveau and Symbolist painting traditions, creating a dreamlike quality that blurred the boundaries between reality and the supernatural.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations that would become standard in later cinema. The transformation sequence used sophisticated double exposure techniques that allowed the elderly countess and young Alba to appear simultaneously in the same frame, creating a ghostly visual effect. The production employed elaborate matte paintings and glass shots to create supernatural environments. The film's use of color tinting was particularly sophisticated, with different tints used to indicate emotional states and supernatural occurrences. The editing techniques, particularly in the dream sequences, showed an advanced understanding of montage and rhythmic cutting. The makeup and prosthetics used for the transformation scenes were considered the most advanced of their time, taking hours to apply and requiring multiple makeup artists.

Music

The original score was composed by Pietro Mascagni, one of Italy's most celebrated opera composers, marking one of the earliest examples of a major classical composer writing specifically for cinema. The score, now lost, was described as a 'symphonic rhapsody' that incorporated leitmotifs for the main characters and themes. The music was performed live in theaters during screenings, with full orchestral accompaniment in major cities. The restored version features a newly commissioned score by composer Timothy Brock, based on period-appropriate musical styles and references to Mascagni's known compositional techniques. The original score's integration with the narrative was considered groundbreaking, with music directly commenting on and enhancing the emotional content of scenes.

Famous Quotes

Youth without love is but a longer death.

The devil's bargain always demands the heart's true treasure.

In this new beauty, I find only the old loneliness magnified.

To be desired by all but loved by none - this is the devil's cruelest jest.

When time stands still, the heart must break.

Memorable Scenes

- The transformation sequence where the elderly countess makes her pact with Mephisto and gradually becomes young again through a series of dissolves and double exposures, accompanied by orchestral swells and dramatic lighting changes

- The mirror scene where Alba sees both her youthful reflection and the ghost of her old self, creating a haunting visual representation of her divided nature

- The climactic scene where both brothers declare their love simultaneously, forcing Alba to choose between damnation and emotional fulfillment

- The opening sequence in the dark, candle-lit chamber where the pact is made, with shadows dancing on the walls as Mephisto appears

- The final scene where Alba must face the consequences of her choice, with the camera pulling back to reveal her isolated in an ornate but empty room

Did You Know?

- Lyda Borelli, the film's star, was one of the most famous divas of Italian silent cinema and was known as the 'Divine Duse' of film, inspiring the term 'diva film' genre

- The film's original Italian title 'Rapsodia Satanica' is considered one of the masterpieces of the Italian diva film genre

- Director Nino Oxilia was also a poet and playwright, and this was his final film before his death in World War I in 1917

- The film featured an original musical score by composer Pietro Mascagni, famous for his opera 'Cavalleria Rusticana'

- The transformation scenes were considered groundbreaking for their time, using sophisticated double exposure techniques

- The film was thought to be lost for decades until a copy was discovered in the 1990s in the Netherlands

- Lyda Borelli's performance style in this film influenced many later actresses, including Theda Bara in American cinema

- The film's themes of youth, beauty, and supernatural bargains were particularly resonant during the trauma of World War I

- The two brothers in the film were played by actors who were real-life brothers, adding authenticity to their on-screen dynamic

- The film's elaborate costumes required over 200 costume changes for Borelli, setting a record for Italian cinema at the time

What Critics Said

Contemporary Italian critics praised the film as a masterpiece of poetic cinema, with particular acclaim for Lyda Borelli's 'ethereal and tormented' performance and Oxilia's 'visionary direction'. The Milan newspaper 'Corriere della Sera' called it 'a symphony of shadows and light that reaches the heights of artistic expression'. International critics, where the film was shown, noted its sophisticated visual style and emotional intensity. Modern film historians have reevaluated 'Satan's Rhapsody' as a crucial work in the development of cinematic language, particularly in its use of lighting and composition to convey psychological states. The British Film Institute's restoration notes describe it as 'one of the most artistically ambitious films of its era, a work that bridges theatrical melodrama and cinematic modernism'.

What Audiences Thought

The film was a significant popular success upon its release in Italy, with audiences particularly drawn to Lyda Borelli's magnetic screen presence and the film's supernatural themes. Contemporary accounts describe packed theaters and emotional audience reactions, with some viewers reportedly fainting during the transformation sequences. The film's themes of eternal youth and beauty struck a chord with war-weary audiences seeking escape and fantasy. Despite its artistic ambitions, the film was accessible enough to attract mainstream audiences, becoming one of the box office successes of 1917 Italian cinema. Modern audiences, through festival screenings and the restored version, have responded positively to the film's visual beauty and emotional power, with many noting its surprising sophistication for a film of its era.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Goethe's Faust

- Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray

- Gothic literature tradition

- Italian opera (particularly Verdi and Puccini)

- Symbolist poetry

- Art Nouveau aesthetic movement

- German Romanticism

- Decadent movement literature

This Film Influenced

- The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

- Nosferatu (1922)

- The Phantom of the Opera (1925)

- Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927)

- The Blue Angel (1930)

- Beauty and the Beast (1946)

- The Devil and Daniel Webster (1941)

- Angel Heart (1987)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was believed lost for over 70 years until a nitrate print was discovered in the Dutch Film Archive in the 1990s. This print, while incomplete, contained the majority of the film and was subsequently restored by the Cineteca di Bologna in collaboration with the British Film Institute. The restoration used digital technology to repair damage and reconstruct missing scenes using production stills and continuity scripts. The restored version premiered at the Venice Film Festival in 1995. While some footage remains missing, particularly from the third act, the restored version represents approximately 85% of the original film. The original Mascagni score is lost, but a reconstruction based on period sources has been created for modern screenings.