Suspense.

"A Drama of Real Life"

Plot

In this pioneering thriller, a young mother is left alone with her infant in an isolated country house when her maid abandons them. A menacing tramp breaks into the home, forcing the mother to barricade herself and her baby in a bedroom while desperately trying to contact her husband by telephone. Meanwhile, her husband receives her frantic call and must race home in a stolen car to rescue his family from the intruder. The film builds tension through parallel editing between the mother's terrifying ordeal and the husband's desperate journey home.

Director

About the Production

This film was co-directed by Phillips Smalley and Lois Weber, who were married at the time. Weber not only starred in the film but also co-wrote and co-directed it, making her one of the first women to direct films in Hollywood. The production utilized innovative techniques for its time, including split-screen effects and dramatic camera angles to enhance the suspense.

Historical Background

Made in 1913, 'Suspense' emerged during a pivotal period in cinema's development when filmmakers were transitioning from simple one-reel actualities to more complex narrative films. The film industry was rapidly moving from the East Coast to Hollywood, and Universal Film Manufacturing Company was among the studios establishing the California film colony. This era saw the birth of many film genres and techniques, with directors experimenting with editing, camera movement, and storytelling methods. The film reflects early 20th-century anxieties about domestic security, the vulnerability of women and children, and the tensions between rural isolation and urban encroachment. The telephone's central role in the plot demonstrates how this new technology was changing American life and creating new possibilities for dramatic storytelling.

Why This Film Matters

'Suspense' holds an important place in film history as one of the earliest examples of the thriller genre, predating many of Alfred Hitchcock's innovations by over a decade. The film demonstrated that short-form cinema could deliver sophisticated psychological tension and emotional engagement. Lois Weber's co-directorial role represents a significant milestone for women in film, as she was among the very few women directing major studio productions during this era. The film's technical innovations, particularly its use of split-screen and parallel editing, influenced countless future suspense films. It also helped establish the 'woman in peril' trope that would become a staple of thriller cinema, though here it's handled with unusual agency given to the female protagonist.

Making Of

Lois Weber and Phillips Smalley were a married couple who frequently collaborated on films during this period. Weber was one of the most prolific and influential women in early Hollywood, eventually becoming the highest-paid director of her era. The film was made during Universal's early years when the studio was still establishing itself in the rapidly growing film industry. The production team experimented with camera techniques that would later become standard in thriller filmmaking, including dramatic lighting to create shadows and tension. The isolated house setting was likely filmed on a studio backlot with carefully constructed interiors to maximize the claustrophobic atmosphere.

Visual Style

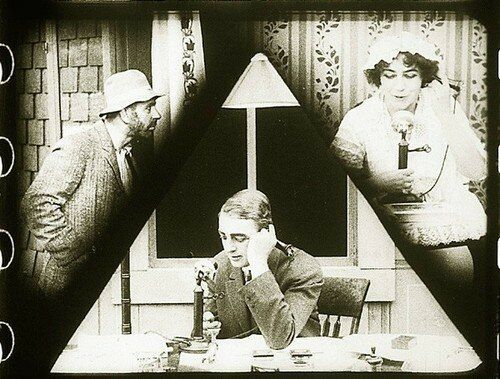

The cinematography by William H. Brown or Billy Bitzer (sources vary) was innovative for its time, featuring dramatic camera angles and lighting techniques that enhanced the film's suspenseful atmosphere. The use of split-screen to show simultaneous action was particularly groundbreaking, allowing audiences to see both the mother's predicament and the husband's desperate journey. Close-ups were employed strategically to emphasize emotional moments, especially the mother's terror and determination. The lighting created dramatic shadows that heightened the sense of menace, particularly in scenes involving the tramp's intrusion.

Innovations

The film's most significant technical achievement was its pioneering use of split-screen to depict simultaneous action, a technique that was highly innovative for 1913. The parallel editing between the mother's ordeal and the husband's journey created a sophisticated narrative structure that built maximum tension. The film also employed subjective camera angles and dramatic lighting that were ahead of their time. The use of the telephone as a plot device demonstrated how filmmakers were incorporating contemporary technology into their narratives. The efficient storytelling within a 10-minute timeframe showed remarkable narrative compression.

Music

As a silent film, 'Suspense' would have been accompanied by live musical performance in theaters. The typical accompaniment would have been piano or organ music, with the musician improvising or using cue sheets provided by the studio. The music would have been designed to enhance the suspenseful moments, with dramatic chords during tense scenes and softer melodies for emotional moments. No original score survives, but modern screenings typically use period-appropriate musical accompaniment.

Famous Quotes

(Intertitle) 'A Drama of Real Life'

(Intertitle) 'The telephone rings...'

(Intertitle) 'Hurry, darling, hurry!'

Memorable Scenes

- The split-screen sequence showing the mother barricading herself while the husband races home

- The mother's desperate telephone call to her husband

- The tramp's menacing approach to the isolated house

- The final confrontation and resolution

Did You Know?

- This is considered one of the earliest examples of the thriller/suspense genre in cinema history

- Lois Weber was one of the first female directors in Hollywood and co-directed this film with her husband Phillips Smalley

- The film features innovative use of split-screen to show simultaneous action, a technique that was groundbreaking for 1913

- The telephone plays a crucial role in the plot, reflecting the technology's growing importance in early 20th century American life

- The film's use of subjective camera angles and close-ups was ahead of its time

- Universal Film Manufacturing Company distributed this film during its early years

- The tramp character was played by Douglas Gerrard, who would later become a prominent character actor

- The film's tension is built through parallel editing between the mother's ordeal and the husband's journey

- This short film was part of Universal's 'Jewel' brand of higher-quality productions

- The baby in the film was played by an infant actor, though their name is not recorded in production records

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews praised the film for its innovative techniques and gripping narrative. The Moving Picture World noted the film's 'unusual dramatic power' and particularly commended the split-screen effect as 'a novel and effective device.' Modern film historians recognize 'Suspense' as a groundbreaking work that anticipated many techniques later associated with classic Hollywood suspense films. Critics have highlighted how the film manages to create genuine tension within its brief runtime and how Weber's direction demonstrates remarkable sophistication for the period. The film is frequently cited in studies of early American cinema and women's contributions to film history.

What Audiences Thought

The film was reportedly well-received by audiences of 1913, who found its suspenseful narrative compelling and emotionally engaging. The combination of domestic drama and criminal elements appealed to the broad audience base that theaters were trying to attract during this period. The film's brevity made it suitable for various programming slots in theater bills. Modern audiences who have seen the film through archival screenings or film society presentations often express surprise at how effectively the film builds tension despite its age and technical limitations compared to modern cinema.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- D.W. Griffith's narrative techniques

- European thriller traditions

- Melodrama conventions

- Stage thriller adaptations

This Film Influenced

- D.W. Griffith's 'The Lonely Villa' (1909)

- Alfred Hitchcock's suspense techniques

- Film noir home invasion narratives

- Modern thriller split-screen techniques

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in archives and has been preserved by film institutions including the Library of Congress. It is available through various film preservation organizations and has been included in collections of early American cinema. The print quality varies depending on the source, but the film remains largely intact and viewable.