The Amazing Quest of Ernest Bliss

"A Millionaire Who Learned to Live!"

Plot

Ernest Bliss, a wealthy and deeply bored young millionaire, visits his Dr. Hale complaining of ennui and lack of purpose in his privileged life. The doctor challenges him to a wager: live and support himself for one year without touching his inheritance, working for a living like ordinary people. If Ernest succeeds, the doctor will pay him £10,000, but if he fails, he must pay the doctor the same amount. Taking on various jobs from dishwasher to window cleaner, Ernest struggles with manual labor and meager wages while meeting Frances Clayton, a charming working-class woman. As he experiences the challenges and dignity of labor, Ernest falls in love with Frances and discovers genuine happiness through purposeful work and authentic relationships, forcing him to confront his own prejudices and ultimately choose between his inherited wealth and his newfound love and purpose.

About the Production

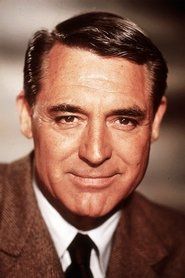

The film was shot quickly during Cary Grant's brief return to England before establishing himself as a Hollywood star. Grant was reportedly paid £5,000 for his role, a significant sum at the time. The production faced challenges with the British weather during exterior shooting scenes, causing delays. The working-class scenes were filmed on constructed sets to maintain control over lighting and sound quality.

Historical Background

Made in 1936, during the height of the Great Depression, this film tapped into widespread anxieties about wealth inequality and the dignity of labor. The 1930s saw increased social consciousness in cinema, with many films exploring class differences and the value of work. In Britain, the period was marked by economic hardship and political tensions as the nation moved toward World War II. The film's themes of a wealthy man discovering value in manual labor resonated with audiences struggling with unemployment and poverty. The rise of labor movements and changing social attitudes toward class made the story particularly relevant to contemporary viewers.

Why This Film Matters

While not a major commercial success, the film represents an important transitional work in Cary Grant's career, showing his development from a British leading man to an international star. The story's premise of wealth redistribution and the value of work reflected growing social consciousness during the Depression era. The film's exploration of class barriers in romance was somewhat progressive for its time, though it ultimately reinforces traditional class structures. Its status as one of Grant's final British films before his Hollywood breakthrough makes it historically significant for film scholars and Grant enthusiasts.

Making Of

The production took place during a transitional period in Cary Grant's career, as he was establishing himself in Hollywood but returned to England for this film. Grant was reportedly difficult on set, feeling the material was beneath his growing stature as a leading man. Director Alfred Zeisler, who had experience in both German and British cinema, struggled with Grant's attitude but managed to complete the film. The working conditions on set reflected the class themes of the movie, with clear distinctions between how cast and crew were treated based on their status. The film's modest budget meant many scenes had to be shot quickly with minimal takes, contributing to its somewhat rushed feel in certain sequences.

Visual Style

The film features typical black and white cinematography of mid-1930s British cinema, photographed by Basil Emmott. The visual style employs standard three-point lighting for interior scenes and natural lighting for exteriors when possible. The cinematography effectively contrasts the sterile, luxurious environments of Ernest's wealthy life with the gritty, textured settings of his working-class experiences. Camera work is straightforward and functional, with few experimental techniques, reflecting the film's modest budget and conventional approach to storytelling.

Innovations

The film employed standard technical practices for British productions of 1936, with no significant innovations or breakthroughs. The sound recording used the typical ribbon microphone technology of the period, resulting in the somewhat muffled audio quality common to films of this era. The production used standard 35mm film stock with typical processing methods of the time. While technically competent for its budget and era, the film offers no notable technical achievements that influenced subsequent filmmaking.

Music

The musical score was composed by Louis Levy, who headed Gaumont British's music department. The soundtrack features typical orchestral arrangements of the period, with light, comedic themes for the opening scenes and more romantic melodies during Ernest's courtship of Frances. The music serves primarily as background accompaniment, never overwhelming the dialogue or action. No original songs were composed for the film, instead using standard stock music common in British productions of the era. The sound quality reflects the technical limitations of 1930s recording equipment.

Famous Quotes

Doctor, I'm bored. I'm so bored I could scream, but it would take too much energy.

You think money buys happiness? I've had more money than I could spend in ten lifetimes, and I've never been more miserable.

There's a peculiar satisfaction in earning your own way in the world.

Love doesn't care about bank accounts or social positions. It only cares about hearts.

Memorable Scenes

- Ernest's first day working as a dishwasher, struggling with the physical demands and discovering the reality of manual labor

- The montage sequence showing Ernest trying various jobs and failing comically at each one

- The romantic scene where Ernest and Frances walk along the Thames at night, with Ernest hiding his true identity

- The climactic scene where Ernest must choose between his inheritance and his new life with Frances

Did You Know?

- This was one of Cary Grant's last British films before becoming a major Hollywood star

- The film is based on the 1919 novel 'The Amazing Quest of Mr. Ernest Bliss' by E. Phillips Oppenheim

- Cary Grant was reportedly unhappy with the film and considered it one of his weaker early performances

- The story was later remade in 1936 as 'The Man Who Could Work Miracles' and again in 1976 as 'The Amazing Mr. Bliss'

- Mary Brian was an American actress who had been a popular silent film star in the 1920s

- Director Alfred Zeisler was a German-born filmmaker who fled Nazi Germany and worked in both British and American cinema

- The film was released in the US under the title 'The Amazing Adventure' to avoid confusion with other similarly titled films

- Grant's character's transformation from bored aristocrat to working man reflected themes popular during the Great Depression era

- The film was considered lost for many years before a print was discovered and restored in the 1990s

- Peter Gawthorne, who plays Dr. Hale, was a veteran character actor who appeared in over 80 films between 1929 and 1949

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews were mixed to negative, with critics finding the story formulaic and Grant's performance uneven. The Times of London criticized the film's predictable plot but praised Grant's charisma. Modern critics view the film primarily as a historical curiosity, valuable mainly for its place in Grant's filmography. Retrospective analyses note that while the film lacks the sophistication of Grant's later work, it contains hints of the suave charm that would make him a star. The film is generally considered a minor work that fails to fully realize its interesting premise.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception in 1936 was modest, with the film performing adequately in British theaters but failing to generate significant enthusiasm. The film's themes resonated with working-class audiences during the Depression era, though some found the resolution unsatisfying. Modern audiences primarily discover the film through Cary Grant retrospectives and classic film festivals, where it's appreciated more for its historical value than its entertainment qualities. The film has developed a small cult following among Grant completists and fans of 1930s British cinema.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Based on the 1919 novel 'The Amazing Quest of Mr. Ernest Bliss' by E. Phillips Oppenheim

- Influenced by the tradition of 'riches to rags' stories popular in 1930s cinema

- Reflects themes from earlier films like 'The Man Who Came Back' (1931)

This Film Influenced

- The Man Who Could Work Miracles (1936) - similar themes of ordinary man with extraordinary abilities

- Trading Places (1983) - similar premise of wealthy person experiencing poverty

- Arthur (1981) - themes of wealthy man finding meaning beyond money

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was considered lost for many years but a complete 35mm print was discovered in the 1990s and has been preserved by the British Film Institute. The restored version was released on DVD as part of a Cary Grant collection. While not in pristine condition, the surviving print is watchable with some deterioration typical of films of this era. The BFI continues to maintain the film in their archive and occasionally screens it at special retrospectives.