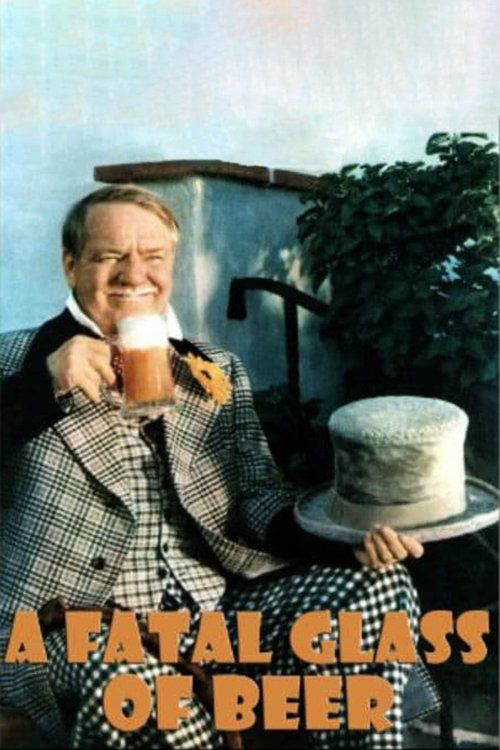

The Fatal Glass of Beer

"A Temperance Tale with a Twist!"

Plot

In the harsh Yukon wilderness during a blizzard 'that ain't fit for man nor beast,' elderly prospector Squire Snavin (W.C. Fields) anxiously awaits the return of his son Chester, who has been away in the city for five years. When Chester finally arrives, he has been corrupted by urban vices, particularly alcohol, much to his father's dismay. The film parodies melodramatic temperance tales as Snavin tries to save his son from the evils of drinking, culminating in a surreal courtroom scene where Chester is tried for his misdeeds. Throughout the short film, Fields repeatedly opens the door to comment on the increasingly absurd weather conditions, creating a running gag that epitomizes the film's absurdist humor.

About the Production

The film was shot in just a few days on a minimal set, relying heavily on Fields' performance and dialogue. The 'blizzard' effect was created using cotton, flour, and a wind machine. The film's surreal quality was enhanced by the decision to have most characters speak in deadpan monotone, creating a deliberately artificial atmosphere. The courtroom scene was filmed in one take to maintain its bizarre, dreamlike quality.

Historical Background

Released in 1933 during the Great Depression and the final years of Prohibition, 'The Fatal Glass of Beer' emerged as a sophisticated parody of both temperance propaganda and the popular Yukon adventure genre. The film's release coincided with the waning of Prohibition, which would be repealed later that year, making its satirical take on temperance particularly timely. The early 1930s saw a boom in short comedy films as theaters needed programming to fill out double bills, and major comedians like Fields used these formats to experiment with material. The film's absurdist approach to comedy was revolutionary for its time, prefiguring the surreal comedy movements that would emerge decades later. The Depression era also saw audiences seeking escapism, making Fields' increasingly bizarre humor a welcome distraction from economic hardships.

Why This Film Matters

'The Fatal Glass of Beer' represents a pivotal moment in American comedy, marking the transition from vaudeville-inspired slapstick to more sophisticated, absurdist humor. The film's deliberate artificiality and self-aware parody helped establish the meta-comedy genre that would later influence everyone from the Marx Brothers to modern comedians. Fields' deadpan delivery and the film's surreal gags became templates for future comedy, particularly in how they subverted audience expectations. The movie's public domain status ensured its preservation and widespread distribution, making it accessible to multiple generations of comedy enthusiasts. Its influence can be seen in the work of later absurdist comedians like Ernie Kovacs, Monty Python, and The Firesign Theatre, all of whom employed similar techniques of deadpan delivery and surreal situations. The film also represents an early example of comedy that trusts its audience to understand irony and satire, rather than relying on straightforward gags.

Making Of

The production of 'The Fatal Glass of Beer' was marked by W.C. Fields' increasing creative control over his material. By 1933, Fields had enough clout to essentially direct his own shorts, with Clyde Bruckman serving more as a technical facilitator. The film's deliberately artificial sets and exaggerated acting style were Fields' way of mocking the overly dramatic Yukon films of the era. The famous door-opening gag was reportedly Fields' idea, inspired by his vaudeville days. During filming, the cast and crew found it difficult to maintain straight faces during Fields' deadpan delivery, leading to multiple retakes. The courtroom scene's bizarre testimony and nonsensical legal proceedings were largely improvised, with Fields encouraging his co-stars to deliver their lines with maximum solemnity to heighten the absurdity.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Charles G. Clarke employs a deliberately flat, theatrical style that enhances the film's artificial atmosphere. The camera work is static and formal, mimicking the composition of stage plays rather than films, which reinforces the parody of melodramatic theater. The lighting is harsh and unnatural, particularly in the interior scenes, creating a stark contrast that emphasizes the surreal quality of the proceedings. The 'blizzard' sequences use backlighting through the artificial snow to create a dreamlike, otherworldly effect. The courtroom scene is shot with a wide angle that captures the entire absurd proceeding in a single frame, forcing viewers to take in the full scope of the ridiculousness. This deliberate avoidance of cinematic naturalism was revolutionary for its time and contributes significantly to the film's enduring power.

Innovations

While not technically groundbreaking in terms of equipment or innovation, 'The Fatal Glass of Beer' achieved significant artistic advances in comedy filmmaking. The film's use of sound for ironic effect rather than realistic reproduction was ahead of its time. Its deliberate artificiality in set design and visual effects represented a bold rejection of the growing trend toward cinematic realism in the early 1930s. The film's editing style, which maintains long takes of Fields' performance rather than cutting to reaction shots, was unusual for comedy shorts of the era. The successful integration of theatrical performance techniques with film technology created a hybrid style that influenced future comedy filmmakers. The film also demonstrated how minimal production values could be used creatively to enhance rather than limit artistic expression.

Music

The film features a minimal musical score typical of early sound shorts, with stock music used to punctuate dramatic moments ironically. The sound design emphasizes the artificial nature of the production, with exaggerated sound effects for the wind and snow that are deliberately unconvincing. The dialogue recording captures Fields' distinctive gravelly voice and precise delivery, which became one of his most recognizable trademarks. The lack of background music during many scenes creates an uncomfortable silence that enhances the deadpan humor. The film makes innovative use of sound for comedic effect, particularly in the courtroom scene where the echoing acoustics add to the surreal atmosphere. The audio quality, while primitive by modern standards, effectively serves the film's purpose of creating an artificial, theatrical world.

Famous Quotes

'It ain't a fit night out for man nor beast.' (repeated multiple times throughout the film)

'Was you ever bit by a dead bee?' (Fields' character asks nonsensically)

'Don't be a luddy-duddy! Don't be a moon-calf! Don't be a jabbernowl!' (Fields' advice to his son)

'A man who wouldn't cheat to win a horse race is a man with no ambition.' (ironic courtroom testimony)

'The fatal glass of beer! The curse of the working class!' (melodramatic proclamation)

Memorable Scenes

- The recurring gag where Fields opens the door multiple times to comment on the increasingly absurd weather conditions, each time with more exaggerated descriptions of the blizzard

- The surreal courtroom scene where testimony becomes increasingly nonsensical and the legal proceedings break down into absurdity

- The opening sequence where Fields sits by the fire, establishing the film's deadpan, theatrical tone

- The son's return from the city, walking with an exaggerated urban swagger that contrasts comically with the Yukon setting

- The final scene where the family gathers around as if for a happy ending, despite the chaos that has ensued

Did You Know?

- The film is a parody of temperance melodramas that were popular in the early 1930s, despite its title suggesting a serious anti-alcohol message

- W.C. Fields reportedly wrote most of his own dialogue and improvised several scenes during filming

- The famous line 'It ain't a fit night out for man nor beast' became one of Fields' most quoted catchphrases

- The film was considered too bizarre by contemporary audiences and was not particularly successful upon release

- The 'glass of beer' that gives the film its title is never actually shown on screen

- Director Clyde Bruckman was a frequent collaborator with Fields and directed many of his classic shorts

- The film fell into the public domain early due to copyright renewal issues, which helped it gain cult status through frequent television broadcasts

- The artificial snow used in filming was actually corn flakes painted white, which would crunch loudly underfoot during takes

- Fields performed the role while suffering from a severe cold, which ironically enhanced his portrayal of a man battling harsh weather

- The film's absurdist style was decades ahead of its time and influenced later surrealist comedians like Monty Python

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics in 1933 were largely confused by the film's avant-garde approach to comedy, with Variety noting its 'peculiar style' and 'unconventional humor' without明确 endorsing or condemning it. Many mainstream reviewers found the film too bizarre for general audiences. However, over time, critical opinion has shifted dramatically, with modern critics hailing it as a masterpiece of surrealist comedy. Leonard Maltin called it 'one of Fields' most daring and successful experiments in absurdist humor.' The American Film Institute later included it in their list of essential American comedies. Contemporary critics particularly praise the film's deadpan delivery, its ahead-of-its-time meta-humor, and Fields' performance as a masterclass in comedic timing. The film is now studied in film schools as an example of early surrealist cinema and has been the subject of numerous academic papers on comedy theory.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reception in 1933 was lukewarm at best, with many theatergoers finding the film too strange and lacking the straightforward slapstick they expected from comedy shorts. However, as the film entered the public domain and began appearing on television in the 1950s and 1960s, it developed a strong cult following. Comedy enthusiasts and Fields fans began to appreciate its sophisticated humor and experimental nature. Modern audiences, particularly those familiar with absurdist and surrealist comedy, have embraced the film as a groundbreaking work. The film's reputation has grown significantly through home video releases and internet streaming, where new generations have discovered its unique charm. Today, it's considered essential viewing for anyone studying the evolution of American comedy, and its most famous gags are still referenced in popular culture.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards were given for short comedy films in this category during 1933

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Temperance movement propaganda films

- Yukon adventure melodramas

- Vaudeville comedy traditions

- Surrealist art movement

- Theatrical melodrama

- Silent film comedy techniques

This Film Influenced

- The Bank Dick (1940)

- Never Give a Sucker an Even Break (1941)

- Monty Python's Flying Circus (1969-1974)

- Eraserhead (1977)

- The Big Lebowski (1998)

- Napoleon Dynamite (2004)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has survived in excellent condition and is in the public domain. Multiple high-quality copies exist in various film archives, including the Library of Congress and the UCLA Film & Television Archive. The film has been restored several times for home video releases, most notably for The Criterion Collection's W.C. Fields box set. Its public domain status has actually helped ensure its preservation through widespread distribution, though it has also resulted in many poor-quality copies circulating. The original negative is believed to be lost, but excellent 35mm prints exist that have been used for modern restorations.