The Glorious Adventure

"When London Burned, Love Rose From the Ashes"

Plot

The Glorious Adventure follows the story of an Earl's cousin who miraculously survives a near-drowning incident, only to find himself thrust into one of London's most catastrophic events. Set against the backdrop of 1666, the protagonist becomes an unlikely hero when he discovers his courage during the Great Fire of London. As flames engulf the city, he risks his life to rescue a noble lady from the inferno, navigating through burning streets and collapsing buildings. The film combines historical drama with personal heroism, showcasing how ordinary people can rise to extraordinary circumstances in times of crisis. Their survival and romance blossom amidst the ashes of the devastated city, symbolizing hope and rebirth in the face of disaster.

About the Production

The film featured elaborate sets recreating 17th-century London and utilized pioneering special effects for the fire sequences. The Great Fire scenes were particularly ambitious for their time, requiring extensive miniature work and matte paintings. Director J. Stuart Blackton, known for his technical innovations, employed multiple camera techniques to create the illusion of the massive fire. The production faced significant challenges in safely simulating the historic fire while maintaining authenticity.

Historical Background

The Glorious Adventure was produced during a significant transitional period in British cinema. The early 1920s saw British film studios attempting to compete with American productions by creating ambitious historical epics. The film's focus on the Great Fire of London resonated with contemporary audiences who were still processing the aftermath of World War I and the social changes it brought. The 1920s was also a period when British cinema was establishing its identity separate from Hollywood, with directors like J. Stuart Blackton bringing international expertise to British productions. The film's emphasis on British history reflected a post-war nationalistic sentiment and a desire to celebrate British resilience and heritage. The technical innovations in depicting the fire also coincided with cinema's evolution toward more sophisticated special effects and spectacle.

Why This Film Matters

The Glorious Adventure represents an important milestone in the development of the British historical epic genre. It demonstrated that British studios could produce spectacles rivaling American productions, paving the way for later historical films like The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933). The film's depiction of the Great Fire of London helped cement this historical event in popular culture, making it accessible to mass cinema audiences. Diana Manners' casting also reflected the growing trend of using real aristocrats in film roles, blurring the lines between social class and celebrity culture. The technical achievements in recreating the disaster sequences influenced subsequent disaster films and established new standards for special effects in British cinema. The film's romantic subplot set against historical tragedy became a template for many later historical dramas.

Making Of

The production of The Glorious Adventure was a significant undertaking for British cinema in 1922. Director J. Stuart Blackton brought his extensive American film experience to this British production, implementing advanced techniques he had developed during his pioneering career. The fire sequences required innovative approaches, including the use of painted glass, double exposures, and carefully controlled studio fires. The cast underwent extensive period costume fittings, with authentic 17th-century clothing recreated by prominent theatrical costumers of the day. Diana Manners, despite her aristocratic background, proved to be a capable actress, though her fame as a socialite often overshadowed her performance reviews. The film's production schedule was extended due to the complexity of the fire effects, with the studio investing heavily in safety measures for the cast and crew during the burning sequences.

Visual Style

The cinematography of The Glorious Adventure was handled by leading British cameramen of the period, utilizing the latest techniques available in 1922. The film employed multiple camera setups for the fire sequences, creating dynamic angles that enhanced the sense of chaos and danger. The use of tinting and toning was particularly effective in the fire scenes, with amber and red tones creating a realistic sense of heat and destruction. The cinematography contrasted the intimate romantic scenes with the epic scale of the disaster, using different lighting techniques to establish mood. The recreation of 17th-century London required careful attention to period detail in lighting and composition, with the cinematographers studying historical paintings of the era for reference. The film also made early use of miniature photography combined with live action, a technique that was still in its developmental stages.

Innovations

The Glorious Adventure featured several technical innovations for its time, most notably in its recreation of the Great Fire of London. The production utilized a combination of techniques including forced perspective miniatures, matte paintings, and carefully controlled studio fires to create the illusion of a city burning. The film employed multiple exposure techniques to layer different elements of the fire sequences, creating a more complex and realistic effect than single shots could achieve. The special effects team developed new methods for safely simulating burning buildings, using a combination of real flames controlled by safety crews and optical effects. The film also featured early examples of continuity editing in action sequences, maintaining spatial coherence during the chaotic fire scenes. These technical achievements represented significant advances in British cinema's capability to produce large-scale spectacle films.

Music

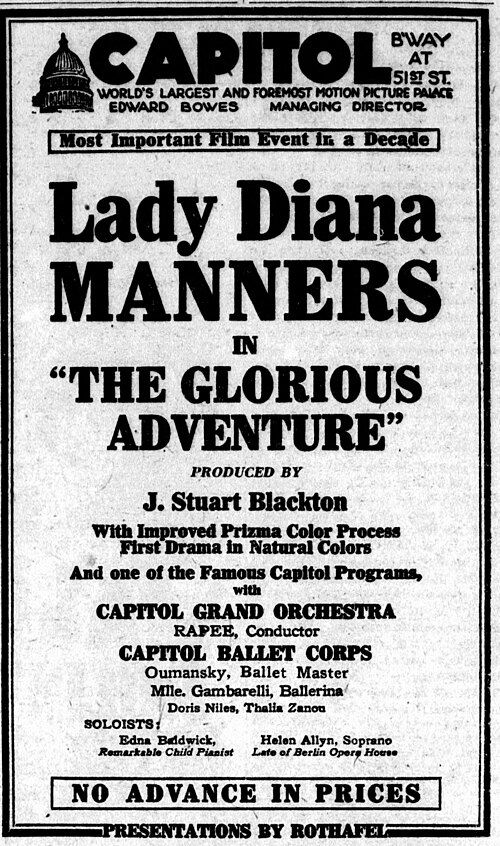

As a silent film, The Glorious Adventure would have been accompanied by live musical performances during its original theatrical run. The score was likely compiled from classical pieces and popular melodies of the era, adapted to suit the dramatic and romantic elements of the story. For the fire sequences, dramatic and tension-building music would have been employed, possibly including works by composers like Wagner or Tchaikovsky known for their powerful orchestral writing. The romantic scenes would have featured lighter, more melodic accompaniment. Large urban theaters might have employed small orchestras, while smaller venues would have used piano or organ accompaniment. No original composed score for the film survives, though contemporary accounts suggest the musical accompaniment significantly enhanced the viewing experience, particularly during the spectacular fire sequences.

Did You Know?

- Diana Manners, who starred in the film, was actually Lady Diana Cooper, a famous British socialite and beauty who later became an actress and author

- Director J. Stuart Blackton was one of the pioneers of American cinema and co-founder of Vitagraph Studios before moving to England

- The film's recreation of the Great Fire of London was considered one of the most ambitious special effects sequences in British cinema up to that point

- The production used over 500 extras for the crowd scenes depicting panicked Londoners fleeing the fire

- Gerald Lawrence was a prominent stage actor who made relatively few film appearances, making this role particularly notable

- The film was one of the first British productions to attempt such a large-scale historical disaster recreation

- J. Stuart Blackton was known as 'The Father of American Animation' before focusing on live-action features

- The original negative was believed lost for decades before a partial print was discovered in the 1970s

- The film's title was changed in some markets to 'The Great Fire of London' to emphasize the historical spectacle

- Contemporary newspapers praised the film's 'thrilling realism' in depicting the 1666 disaster

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised The Glorious Adventure for its ambitious scope and technical achievements, particularly the fire sequences which were described as 'breathtaking' and 'realistically terrifying' in reviews of the time. The Times noted that 'Mr. Blackton has succeeded in creating a spectacle of considerable magnitude' while the Picturegoer magazine highlighted Diana Manners' 'graceful performance' despite her relative inexperience to the screen. Modern film historians view the work as an important example of early British attempts at large-scale historical productions, though some note that the dramatic elements occasionally take a backseat to the spectacle. The film is now recognized more for its technical innovations and historical importance than for its narrative or artistic merits, though it remains a significant artifact of 1920s British cinema.

What Audiences Thought

The Glorious Adventure was moderately successful with British audiences upon its release in 1922, particularly drawing viewers interested in historical subjects and spectacular effects. Contemporary audience reports indicate that the fire sequences generated considerable excitement and discussion among moviegoers, with many newspapers reporting on the 'thrilling' nature of these scenes. The presence of the famous Lady Diana Cooper in the cast also attracted curiosity from the public, though some traditionalists questioned the appropriateness of aristocracy appearing in motion pictures. The film performed well in London and major provincial cities, though its appeal was more limited in rural areas where historical epics were less popular. Audience letters published in film magazines of the period generally praised the film's spectacle while some found the romantic subplot somewhat conventional.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards documented for this film

Film Connections

Influenced By

- D.W. Griffith's historical epics

- Italian historical spectacles

- Contemporary disaster literature

- Paintings of the Great Fire of London

- Stage melodramas of the period

This Film Influenced

- London Symphony

- 1927

- The Great Game

- 1930

- Fire Over England

- 1937

- London Belongs to Me

- 1948

- The Great Fire of London

- TV series, 1979)