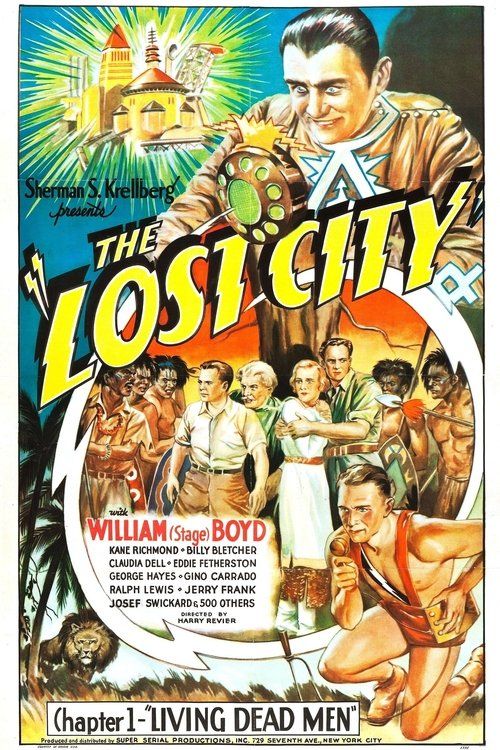

The Lost City

"The Most Amazing Serial Ever Produced!"

Plot

The Lost City follows the adventures of scientist Bruce Gordon (William 'Stage' Boyd) and his expedition as they venture into the African jungle to investigate mysterious seismic activities. They discover the hidden city of Zoloz, ruled by the evil scientist Dr. Manyus, who has developed a powerful earthquake machine that he plans to use to destroy civilization and establish himself as world ruler. Gordon, along with his colleagues Jerry (Kane Richmond) and Mary (Claudia Dell), must battle through numerous perils including hostile tribes, giant spiders, and the scientist's mechanical minions to stop the catastrophic weapon. The serial unfolds across twelve thrilling chapters, each ending in a cliffhanger as the heroes face increasingly dangerous obstacles in their mission to save the world from Manyus's destructive ambitions.

About the Production

The film was shot on an extremely low budget, with many scenes utilizing stock footage from other jungle films. The 'giant spiders' were actually regular spiders filmed against miniature sets and then composited. Production was rushed, completing in just three weeks. The earthquake effects were achieved through camera shake and miniature destruction. Many of the African tribal scenes featured African-American actors from Harlem in stereotypical roles, which was common practice at the time.

Historical Background

Released in 1935, The Lost City emerged during the height of the Great Depression, when audiences sought escapist entertainment. The film reflected contemporary anxieties about scientific advancement and the potential for technology to be used for destructive purposes, particularly in the aftermath of World War I and amid rising tensions in Europe. The serial format was extremely popular during this period, providing weekly entertainment at an affordable price. The depiction of an African setting with hidden civilizations played into popular colonial-era fantasies about unexplored territories and 'lost worlds,' themes that were prevalent in literature and film of the 1930s. The film's focus on a scientist attempting world domination also mirrored growing fears about authoritarian regimes and technological warfare.

Why This Film Matters

The Lost City represents an important example of the science fiction serial genre that flourished in the 1930s. While not critically acclaimed, it exemplifies the serial format's contribution to American cinema history, particularly in developing serialized storytelling techniques that would later influence television series. The film's portrayal of scientific hubris and the dangers of unchecked technological advancement became recurring themes in science fiction. Its depiction of Africa and indigenous peoples, while stereotypical by modern standards, reflects the colonial attitudes prevalent in 1930s American popular culture. The serial format itself was significant in creating weekly audience engagement and building anticipation through cliffhanger endings, a narrative device that continues to influence modern media.

Making Of

The production of The Lost City was typical of poverty row filmmaking of the 1930s. Director Harry Revier worked with minimal resources, often having to complete scenes in single takes due to budget constraints. The cast performed many of their own stunts, leading to several injuries during filming. The earthquake sequences were created using simple techniques including shaking the camera and throwing debris at the actors. The 'lost city' itself was constructed from leftover set pieces from other productions. William 'Stage' Boyd, who played the villain Dr. Manyus, was allegedly difficult on set, often demanding script changes to increase his character's prominence. The serial was filmed out of sequence to maximize the use of sets and locations, a common practice for serial productions of the era.

Visual Style

The cinematography by James Diamond utilized basic techniques typical of low-budget productions of the era. The film employed static camera setups for dialogue scenes and more dynamic movement during action sequences. The jungle scenes used forced perspective and matte paintings to create the illusion of vast, exotic locations. The earthquake effects were achieved through handheld camera work and deliberate camera shake. The serial made extensive use of rear projection for background elements, a common cost-saving measure. The black and white photography often employed high contrast lighting to create dramatic shadows, particularly in scenes featuring Dr. Manyus's laboratory.

Innovations

While not technically innovative, The Lost City employed several creative solutions to overcome budget limitations. The earthquake effects, while primitive, were effective for their time and audience expectations. The serial made use of early compositing techniques to create the illusion of giant creatures. The production team developed efficient methods for rapid scene changes to accommodate the serial's compressed shooting schedule. The film's use of existing footage from other productions was an early example of what would later become common practice in low-budget filmmaking. The cliffhanger endings were carefully structured to maximize audience retention week to week.

Music

The musical score was compiled from stock music libraries rather than being originally composed for the film. Typical of serial productions, the soundtrack used dramatic orchestral pieces to punctuate action scenes and romantic themes for scenes involving the leads. Sound effects were created live during projection in many theaters, with projectionists adding their own effects for the earthquake sequences. The film's audio quality was limited by the recording technology of the time, with noticeable hiss and limited frequency range. Dialogue was recorded using early microphone technology, resulting in somewhat flat sound reproduction.

Famous Quotes

With my earthquake machine, I shall bring the world to its knees!

The power of the earth itself shall be my weapon!

No one can stop the destruction I will unleash upon civilization!

In the heart of Africa lies the secret to ultimate power!

You fools think you can stop progress? I AM progress!

Memorable Scenes

- The first activation of the earthquake machine, with miniature buildings shaking and collapsing

- The heroes' encounter with the giant spiders in the jungle caverns

- Dr. Manyus's dramatic reveal of his laboratory and the earthquake device

- The final confrontation in the lost city as the earthquake machine goes out of control

- The cliffhanger ending of Chapter 6 with the heroes trapped in a flooding chamber

Did You Know?

- William 'Stage' Boyd was often confused with William Boyd of Hopalong Cassidy fame, leading to career problems for both actors

- The serial was originally titled 'The Lost City of Manyus' but was shortened for release

- Only eight of the twelve chapters are known to survive in complete form today

- The earthquake machine prop was repurposed from a previous science fiction film

- Claudia Dell was a former Ziegfeld Follies girl making one of her few film appearances

- The film was re-released in 1949 as a feature film titled 'Lost City of the Jungle' with new footage added

- Director Harry Revier was known as the 'King of Serials' in the 1930s

- The jungle sets were the same ones used in the Tarzan films starring Johnny Weissmuller

- The serial was banned in several countries due to its depiction of scientific weapons of mass destruction

- Kane Richmond would later become famous for starring in the Spy Smasher serial series

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception was generally negative, with most reviewers dismissing the serial as low-budget entertainment. The New York Times criticized its 'far-fetched plot' and 'unconvincing special effects.' Variety noted that while the serial would appeal to children, adults would find it lacking in substance. Modern reassessments recognize The Lost City as a representative example of 1930s serial filmmaking, with film historians noting its place in the development of the science fiction genre despite its technical limitations. Some contemporary critics appreciate the serial's earnest approach to its genre conventions and its historical value as a document of 1930s popular culture.

What Audiences Thought

The Lost City was moderately successful with its target audience of serial enthusiasts and children. Weekly attendance remained steady throughout its theatrical run, indicating that the cliffhanger format effectively maintained audience interest. Many viewers of the era reportedly enjoyed the formulaic nature of the serial and the predictable weekly resolution of immediate dangers. The film developed a cult following among serial fans in subsequent decades, with home movie collectors seeking out rare chapters. Modern audiences encountering the film often view it through the lens of historical curiosity, appreciating its place in cinema history while acknowledging its dated elements and technical limitations.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- King Kong (1933)

- The Most Dangerous Game (1932)

- Tarzan the Ape Man (1932)

- Flash Gordon (1936)

- H. Rider Haggard's novels

This Film Influenced

- Undersea Kingdom (1936)

- Flash Gordon (1936)

- The Phantom Creeps (1939)

- King of the Rocket Men (1949)

- Commando Cody: Sky Marshal of the Universe (1953)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Lost City is partially lost, with only 8 of the 12 chapters known to survive in complete form. The surviving chapters exist in various archives including the Library of Congress and private collections. Some fragments of the missing chapters exist as incomplete reels. The film has been partially restored by film preservation societies, though the quality varies depending on the source material. The 1949 re-release version 'Lost City of the Jungle' survives more completely but contains significant alterations and added footage.