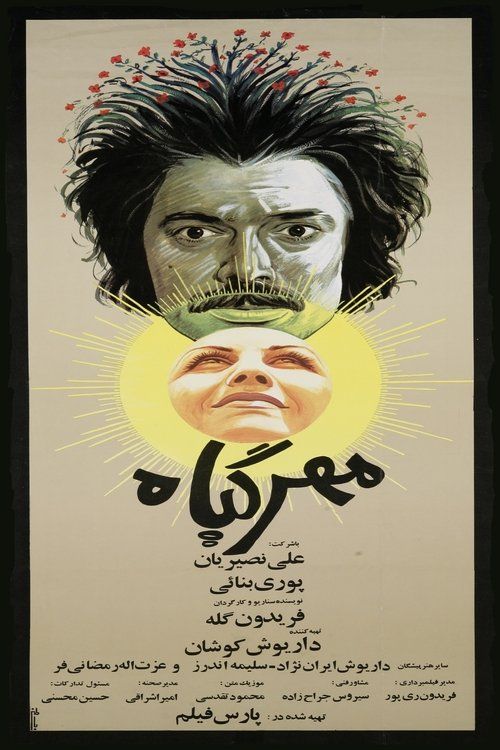

The Mandrake

Plot

Ali, a humble flower seller living on the outskirts of the city, struggles to survive after his aunt illegally seizes his inherited land. One fateful night while driving, he encounters Mehri, a mysterious woman fleeing from unknown pursuers. She accepts his offer for a ride, and an intense romantic attraction quickly develops between them. Their budding relationship takes a dramatic turn when Mehri visits her grandmother's house under the pretense of a family visit and never returns, leaving Ali devastated and questioning whether their connection was genuine or part of a larger scheme. The film explores themes of trust, betrayal, and class struggle in 1970s Iranian society.

About the Production

The Mandrake was produced during the golden age of Iranian cinema before the 1979 revolution. Director Fereydoun Gole, known for his social realist style, faced challenges from censorship boards due to the film's critical portrayal of social inequality and corruption. The production utilized actual locations in Tehran's working-class neighborhoods to maintain authenticity. The flower shop scenes were filmed in a real flower market, with Ali Nasirian spending weeks learning the trade from actual flower sellers to perfect his performance.

Historical Background

The Mandrake was produced during a pivotal period in Iranian history, just four years before the 1979 Islamic Revolution. The mid-1970s saw significant social and economic changes under the Shah's modernization policies, creating a growing divide between traditional and Westernized segments of society. This era, often referred to as the Iranian New Wave cinema movement, witnessed filmmakers exploring previously taboo subjects like class struggle, corruption, and social injustice. The film's release coincided with increasing political unrest and growing opposition to the Pahlavi regime. Cinema had become one of the few mediums where social critique could be expressed, albeit subtly, making films like The Mandrake important cultural artifacts of pre-revolutionary Iran. The oil boom of the early 1970s had created unprecedented wealth, but this prosperity was unevenly distributed, leading to the very social tensions depicted in the film.

Why This Film Matters

The Mandrake stands as a quintessential example of Iranian New Wave cinema, representing the artistic flowering that occurred before the revolution. The film's portrayal of urban poverty and social inequality was groundbreaking for its time, bringing attention to issues rarely addressed in Iranian media. Its realistic depiction of Tehran's working class and critique of corruption resonated deeply with audiences, making it a box office success despite its serious themes. The film's ambiguous ending and complex characters influenced a generation of Iranian filmmakers who would later emerge after the revolution. The Mandrake is often cited by film scholars as an important bridge between the commercial cinema of the 1960s and the more artistically ambitious works of the late 1970s. Its preservation of pre-revolutionary Persian dialect and urban landscapes makes it an invaluable historical document. The film's themes of dispossession and injustice continue to resonate with contemporary Iranian audiences, and it remains a reference point for discussions about social cinema in Iran.

Making Of

Director Fereydoun Gole was known for his meticulous attention to detail and insistence on authenticity. During pre-production, he spent months researching the lives of Tehran's working class, often disguised as a flower vendor himself. The casting process was particularly challenging for the role of Mehri, as Gole sought an actress who could convey both vulnerability and mystery. Pouri Banaei was discovered after Gole saw her in a theatrical performance and was struck by her ability to command attention without dialogue. The film's most challenging scene involved a night shoot on the outskirts of Tehran where Ali first encounters Mehri. The crew faced difficulties with lighting equipment in the remote location, leading to innovative solutions using car headlights and natural moonlight. The relationship between the two leads was carefully developed through extensive rehearsals, with Gole encouraging improvisation to create natural chemistry. The film's controversial themes led to several confrontations with Iranian censors, who demanded cuts to scenes depicting social inequality. Gole fought to maintain his artistic vision, ultimately compromising only minimally to ensure the film's release.

Visual Style

The Mandrake's black and white cinematography, executed by Maziar Partow, is characterized by its stark contrasts and documentary-like realism. Partow employed natural lighting whenever possible, particularly in the outdoor scenes, to create an authentic sense of place and time. The camera work often uses handheld techniques during the more dramatic sequences, creating a sense of immediacy and emotional turbulence. The film's visual style draws heavily from Italian neorealism, with long takes and deep focus compositions that allow the social environment to play as important a role as the characters themselves. The flower shop scenes are particularly notable for their use of close-ups, capturing both the beauty of the flowers and the weariness on Ali's face. The night sequences, especially the crucial scene where Ali first meets Mehri, utilize chiaroscuro lighting to create an atmosphere of mystery and danger. The cinematography also pays careful attention to the urban landscape of 1970s Tehran, preserving images of neighborhoods that have since been transformed or demolished.

Innovations

The Mandrake was technically innovative for its time, particularly in its use of location shooting and natural lighting. The film's sound recording was challenging due to the noisy urban environments where much of it was shot, requiring innovative microphone placement and post-production synchronization techniques. The production team developed new methods for filming in Tehran's crowded markets without disrupting daily commerce, using hidden cameras and non-professional extras. The film's editing, particularly in the sequence showing Ali's daily routine, employed jump cuts and montage techniques that were relatively new to Iranian cinema at the time. The makeup department created realistic aging effects for the grandmother character using techniques that were pioneering in Iranian film. The film's special effects, though minimal, included clever use of double exposure for dream sequences that added psychological depth to the narrative. The production also implemented a new system for tracking continuity across multiple location shoots, which was particularly challenging given the film's episodic structure and numerous outdoor scenes.

Music

The film's score was composed by Hossein Dehlavi, one of Iran's most respected classical composers who was known for blending traditional Persian musical elements with Western classical forms. The soundtrack features a minimalist approach, with Dehlavi using primarily solo instruments to underscore key emotional moments. The main theme, played on the santur (a traditional Persian hammered dulcimer), recurs throughout the film, its variations reflecting the changing emotional states of the characters. During the more suspenseful sequences, Dehlavi incorporates dissonant strings and sparse percussion to build tension. The film also makes effective use of diegetic sound, particularly the ambient noises of Tehran's streets and the flower market. The soundtrack was released as a separate album and became popular in its own right, with the main theme becoming particularly beloved among Iranian music lovers. Dehlavi's score was praised for its ability to enhance the film's emotional depth without overwhelming the narrative, a delicate balance that many considered his finest work for cinema.

Famous Quotes

Sometimes the most beautiful flowers grow in the darkest corners of the city.

Trust is like a flower - once it's crushed, it never returns to its original form.

In this city, even shadows have their price.

We all carry gardens in our hearts, but some of us only know how to sell the flowers.

The road to truth is often paved with good intentions and broken promises.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing Ali's daily routine at the flower market, capturing the beauty and hardship of his work through a series of wordless vignettes.

- The pivotal night scene where Ali first encounters Mehri on the deserted road, their silhouettes framed against the car's headlights creating an atmosphere of both danger and possibility.

- The intimate conversation in Ali's small apartment where the two characters share their life stories, the camera slowly pushing in as their emotional connection deepens.

- The final scene where Ali returns to the spot where he first met Mehri, holding a single flower as the camera pulls back to show him alone against the vast urban landscape.

Did You Know?

- The film's original Persian title 'Gol-e Yakh' literally translates to 'Ice Flower,' though it was marketed internationally as 'The Mandrake' due to the mystical connotations of the plant in Western culture.

- Ali Nasirian, who plays Ali, was one of Iran's most respected actors and had previously worked with director Fereydoun Gole on several successful projects.

- The film was shot in black and white despite color film being available, as Gole believed it better captured the stark realities of urban poverty.

- Pouri Banaei's performance as Mehri was her breakout role, though she would retire from acting just a few years later.

- The car used in the film belonged to the director himself and was a common model in 1970s Iran, adding to the film's authenticity.

- The film's screenplay was based on a short story by Gole himself, which he had written years earlier but struggled to get produced due to its controversial themes.

- The grandmother's house was an actual residence in Tehran's old district, and the elderly woman who appears briefly was the real homeowner.

- The film was banned from international festivals for several years due to its political undertones.

- The flower arrangements seen throughout the film were created by a professional florist who was hired specifically for the production.

- The film's ending was deliberately ambiguous, sparking debates among Iranian critics and audiences about Mehri's true fate and motives.

What Critics Said

Contemporary Iranian critics praised The Mandrake for its bold social commentary and technical excellence. The film was hailed as a masterpiece of social realism, with particular acclaim for Ali Nasirian's nuanced performance as the struggling flower seller. Critics noted how Gole's direction balanced melodrama with documentary-like observation, creating a work that was both emotionally engaging and socially relevant. The film's cinematography, particularly its use of shadows and light to reflect the characters' emotional states, was widely praised. International critics who saw the film at festivals noted its universal themes despite its specifically Iranian setting. In retrospect, film scholars consider The Mandrake one of the most important Iranian films of the 1970s, often comparing it favorably to the works of contemporaries like Abbas Kiarostami and Sohrab Shahid Saless. The film's reputation has grown over time, with many modern critics viewing it as a prescient work that captured the social tensions leading to the 1979 revolution.

What Audiences Thought

The Mandrake was a commercial success upon its release in Iran, resonating particularly with working-class audiences who saw their own struggles reflected in Ali's story. The film's realistic portrayal of urban life and its critique of social injustice struck a chord with viewers experiencing similar hardships. Audiences were especially moved by the chemistry between the leads and the film's bittersweet ending, which sparked extensive debate and discussion in theaters and cafes across Tehran. The film's popularity extended beyond urban centers to smaller cities, where its themes of land dispossession and family betrayal were particularly relevant. Despite its serious tone, the film managed to attract a broad demographic, from young intellectuals to older traditional viewers. In the years following its release, The Mandrake developed a cult following among Iranian cinema enthusiasts, with many considering it one of the most emotionally powerful films of the pre-revolutionary era. The film's reputation has endured among Iranian diaspora communities, where it is often screened at cultural events and film festivals.

Awards & Recognition

- Best Director - Sepas Film Festival, Tehran (1975)

- Best Actor - Ali Nasirian at the Tehran International Film Festival (1975)

- Best Screenplay - Fereydoun Gole at the Iranian Film Critics Awards (1976)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Italian Neorealism (particularly the works of De Sica and Rossellini)

- French New Wave cinema

- The social realist tradition in Iranian literature

- Earlier Iranian films by directors like Dariush Mehrjui

- Classic film noir traditions

- Documentary filmmaking techniques

This Film Influenced

- Later Iranian social realist films of the late 1970s

- Post-revolutionary Iranian cinema dealing with social themes

- Contemporary Iranian films exploring urban alienation

- Works by directors who emerged from the Iranian New Wave movement

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Mandrake has been partially preserved by the Iranian Film Archive, though several original prints were damaged during the political upheaval of 1979. The film underwent restoration in the early 2000s as part of a project to preserve important works of pre-revolutionary Iranian cinema. A restored version was screened at the 2005 Cannes Film Festival as part of a retrospective on Iranian cinema. Some original negatives remain missing, particularly for certain deleted scenes that were cut due to censorship. The Film Foundation has included The Mandrake in its list of endangered classic films requiring urgent preservation efforts. Digital restoration work was completed in 2018, though purists note that some of the original film's texture was lost in the transfer process.