The Reign of Terror

"A Tale of Love and Sacrifice During the Darkest Days of the French Revolution"

Plot

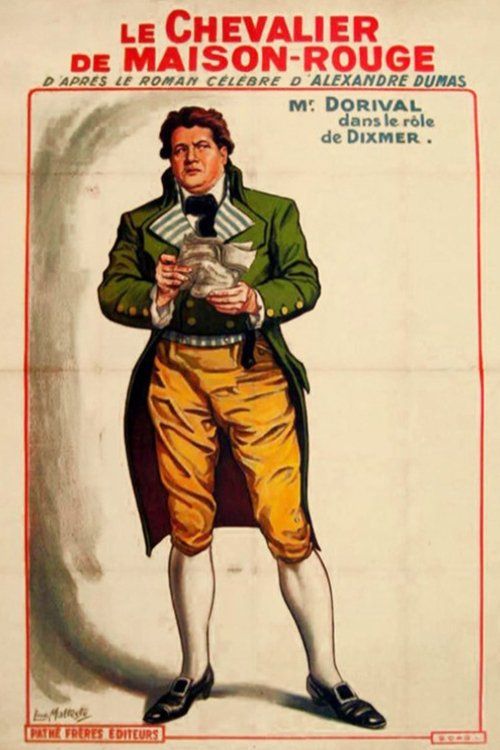

Set in Paris during March 1793 at the height of the French Revolution's Reign of Terror, this historical drama follows the Knight of Maison-Rouge, who operates under the alias Citizen Morand while plotting to rescue Queen Marie-Antoinette from imprisonment. He is aided by his brother-in-law Dixmer, a master tanner who poses as a fervent revolutionary, and Dixmer's wife Geneviève, the Knight's sister trapped in a loveless marriage. During a mission, Geneviève is saved from arrest by Lieutenant Maurice Lindey, sparking a forbidden romance between them despite her marital status. The conspirators dig a secret tunnel from a house rented by Dixmer to the Tower of the Temple where the queen is held prisoner, but multiple rescue attempts fail while Marie-Antoinette faces the imminent threat of the guillotine. As the plot unfolds, Lieutenant Lindey becomes increasingly entangled in the dangerous conspiracy, forcing him to choose between his revolutionary duties and his love for Geneviève.

About the Production

This film was part of Pathé's prestigious series of literary adaptations, utilizing elaborate sets and costumes to recreate Revolutionary Paris. The production employed hundreds of extras for crowd scenes depicting revolutionary mobs. The tunnel sequences were particularly challenging to film in the confined spaces of early studio sets. The film was shot during the early months of World War I, which created additional production difficulties and limited its international distribution.

Historical Background

This film was produced during a fascinating transitional period in both cinema and European history. 1914 marked the end of the Belle Époque and the beginning of World War I, making the film's themes of revolution, political upheaval, and personal sacrifice particularly resonant. The French film industry was at its peak before the war, with Pathé Frères dominating global markets. Historical epics like this one represented French cinema's attempt to establish cultural legitimacy and compete with traditional theater. The film's release just before the war meant it was among the last major French productions to achieve international distribution before the conflict dramatically reshaped the film industry. The choice of Dumas' revolutionary subject matter reflected contemporary French fascination with their national history, while also subtly commenting on the political tensions brewing across Europe.

Why This Film Matters

As one of the early ambitious literary adaptations in cinema, this film helped establish the precedent for bringing classic literature to the screen. Its detailed recreation of Revolutionary France set new standards for historical authenticity in film production. The movie represents the pinnacle of French cinema's artistic achievements before World War I disrupted the industry. The film's treatment of political themes and personal romance during historical turmoil influenced later historical dramas and established narrative patterns that would be refined throughout the silent era. Its production values and attention to detail demonstrated cinema's potential as a serious artistic medium capable of competing with traditional theatrical productions.

Making Of

The production was one of Albert Capellani's most ambitious projects for Pathé, requiring extensive research into Revolutionary period details. The director insisted on historical accuracy, consulting with historians and utilizing authentic period documents for set design. The tunnel sequences presented significant technical challenges for the cinematography team, who had to work with primitive lighting equipment in cramped conditions. The casting of Paul Escoffier as the Knight of Maison-Rouge was considered a coup, as he was one of France's most respected stage actors transitioning to cinema. The film's production was rushed to completion before the anticipated European conflict, which indeed erupted later in 1914 and dramatically affected the film industry. The romantic subplot between Geneviève and Lindey was expanded from Dumas' original novel to appeal to contemporary cinema audiences.

Visual Style

The cinematography by an uncredited Pathé cameraman utilized the advanced techniques available in 1914, including location shooting in Paris for establishing shots and elaborate studio sets for interior scenes. The film employed chiaroscuro lighting effects to create dramatic tension, particularly in the tunnel sequences and night scenes. Camera movement was relatively static, typical of the period, but the composition of shots was carefully planned to emphasize the grand scale of the Revolutionary settings. The cinematography successfully captured both the intimate moments of the romantic subplot and the epic scale of the historical events, demonstrating Pathé's technical capabilities at the height of the pre-war French film industry.

Innovations

The film demonstrated advanced set construction techniques for its period, with detailed recreations of Revolutionary Paris including the Tower of the Temple prison. The tunnel sequences required innovative camera setups and lighting solutions to film effectively in confined spaces. The production utilized Pathé's advanced film stock and processing techniques, resulting in relatively high image quality for the era. The crowd scenes involving hundreds of extras showcased sophisticated coordination and staging capabilities. The film's editing, while basic by modern standards, employed cross-cutting between parallel storylines to build dramatic tension, representing an advanced narrative technique for 1914.

Music

As a silent film, it would have been accompanied by live musical performance in theaters. The original score, likely composed by Pathé's house musicians, would have featured dramatic classical pieces appropriate to the historical setting. French theaters typically employed pianists or small orchestras for such prestigious productions. The music would have emphasized the romantic elements during the Geneviève-Lindey scenes and created tension during the rescue attempts. Contemporary orchestral arrangements of revolutionary songs like 'La Marseillaise' were likely incorporated to enhance the historical atmosphere. No recordings of the original musical accompaniment survive.

Famous Quotes

No surviving intertitles or dialogue cards are documented from this lost film, making direct quotes unavailable. Contemporary promotional materials emphasized themes of 'Love stronger than the guillotine' and 'Courage in the darkest hour of France.'

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic tunnel-digging sequence where conspirators work secretly beneath Revolutionary Paris to reach the imprisoned queen

- Geneviève's narrow escape from arrest and her first meeting with Lieutenant Lindey

- The failed rescue attempts from the Tower of the Temple, showcasing the desperation of the plot

- The climactic scenes depicting the threat of Marie-Antoinette's impending execution

- The romantic moments between Geneviève and Lindey set against the backdrop of revolutionary chaos

Did You Know?

- Based on Alexandre Dumas' 1846 novel 'Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge' (The Knight of Maison-Rouge)

- Director Albert Capellani was one of the pioneering figures in French cinema, known for his literary adaptations

- The film was released just months before the outbreak of World War I, which severely impacted its distribution and reception

- Pathé Frères invested heavily in this production as part of their strategy to compete with theatrical productions

- The film featured one of the earliest detailed recreations of the French Revolution period on screen

- Many of the costumes and props were reportedly authentic or meticulously reproduced from historical sources

- The film was part of a wave of pre-war French historical epics that influenced later international productions

- Contemporary advertisements emphasized the film's 'authentic historical details' and 'dramatic intensity'

- The original French title was 'Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge' rather than 'The Reign of Terror'

- The film's release coincided with heightened interest in French revolutionary themes due to contemporary political tensions

What Critics Said

Contemporary French critics praised the film's ambitious scope and historical accuracy, with particular commendation for the performances and set design. Le Film magazine noted the 'splendid recreation of Revolutionary Paris' and praised Capellani's direction. However, some critics felt the romantic elements detracted from the historical drama's seriousness. International reception was limited due to the outbreak of World War I shortly after release. Modern film historians consider the work an important example of pre-war French cinema's artistic ambitions, though the film itself remains largely unseen due to preservation issues. The film is frequently cited in scholarly works about early French cinema and the development of the historical epic genre.

What Audiences Thought

Initial French audiences responded positively to the film's dramatic storytelling and spectacular elements, particularly the crowd scenes depicting revolutionary Paris. The romantic subplot between Geneviève and Lindey proved especially popular with contemporary viewers. However, the film's theatrical run was cut short by the outbreak of World War I, which led to the closure of many cinemas and redirection of public attention to the war effort. The film's themes of patriotism and sacrifice took on new meanings during the wartime period, though distribution became severely limited. Post-war screenings were rare as the film industry struggled to rebuild and audiences' tastes had shifted.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Alexandre Dumas' novel 'Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge'

- Contemporary French theatrical traditions

- Earlier Pathé historical productions

- Stage melodramas of the Belle Époque

- Romantic literature of the 19th century

This Film Influenced

- Later adaptations of Dumas' works

- French historical epics of the 1920s

- Silent era prison escape films

- Revolutionary dramas of the 1930s

- Historical romance films

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is considered lost or partially lost. Like many films from this era, particularly French productions affected by World War I, complete copies have not survived. Some fragments or still photographs may exist in archives such as the Cinémathèque Française, but a complete version is not known to survive. The loss represents a significant gap in the documentation of Albert Capellani's work and pre-war French cinema achievements. Preservation efforts for films from this period continue, but the chances of recovering a complete print are considered very low.