The Rembrandt in Rue Lepic

Plot

In this early French comedy, a couple eagerly purchases what they believe to be an authentic Rembrandt painting from a street vendor on Rue Lepic in Paris. Their excitement quickly turns to chaos when during a celebratory gathering, a woman accidentally sits on the precious artwork, damaging it. What follows is a wild slapstick chase through the streets of Paris as the couple desperately tries to save their investment and prevent further destruction. The film culminates in a series of comedic mishaps as various characters become entangled in the pursuit of the damaged painting, ultimately revealing the true nature of their supposed masterpiece.

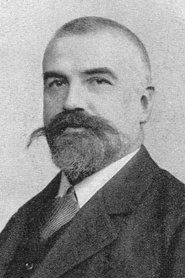

Director

About the Production

This film was part of Jean Durand's series of comedic shorts produced for Gaumont. The location shooting on Rue Lepic was significant as it was a famous artistic street in Montmartre, adding authenticity to the art-themed narrative. The film utilized practical effects and physical comedy techniques typical of the era, with actors performing their own stunts in the chase sequences.

Historical Background

This film was produced in 1910, during what many film historians consider the peak of French cinematic dominance before World War I. The early 1910s saw Paris as the undisputed capital of world cinema, with companies like Gaumont and Pathé leading global production. The film reflects the growing sophistication of cinematic storytelling, moving away from simple actualities toward narrative fiction with character development and plot progression. The art world theme was particularly relevant in 1910 Paris, as the city was experiencing unprecedented artistic innovation with movements like Cubism emerging and the art market becoming increasingly commercialized. The film's slapstick style also represents the evolution of cinematic comedy from the simple gag films of the 1900s to more complex chase narratives that would dominate comedy in the coming decades.

Why This Film Matters

While not as well-known as some contemporary works, 'The Rembrandt in Rue Lepic' represents an important example of early French comedy cinema and the development of the slapstick genre. The film demonstrates how early filmmakers were beginning to use location shooting to add authenticity and visual interest to their narratives. Its art-world theme also reflects the growing intersection between cinema and the established arts in early 20th century Paris, as cinema was struggling to be recognized as a legitimate art form. The film's preservation of Parisian street life from 1910 also provides valuable historical documentation of the city's appearance during this pivotal period. As part of Jean Durand's body of work, it contributes to our understanding of how French comedy evolved and influenced later comic traditions in international cinema.

Making Of

Jean Durand directed this film during his most prolific period at Gaumont, where he was responsible for numerous comedy shorts. The production utilized real Parisian locations, particularly the Montmartre district, which was still an active artistic community in 1910. The chase sequences were filmed using early tracking techniques, with camera operators following the actors through the streets. The cast, led by Ernest Bourbon, were regular collaborators with Durand and had developed a chemistry that allowed for improvisational elements within the structured slapstick routines. The painting prop used in the film was likely a reproduction created specifically for the production, as authentic Rembrandts would have been prohibitively expensive and impractical for film use.

Visual Style

The cinematography, typical of Gaumont productions of the era, utilized stationary cameras for interior scenes and mobile cameras for the exterior chase sequences. The location shooting on Rue Lepic demonstrates the growing sophistication of location cinematography in 1910. The film likely used natural lighting for exterior shots, which was common practice before the development of more sophisticated lighting equipment. The camera work during chase sequences would have been challenging for the period, requiring camera operators to follow the action while maintaining focus and composition. The visual style emphasizes clarity and readability of the action, which was essential for comedy in the silent era.

Innovations

While not groundbreaking in technical terms, the film demonstrates several important technical achievements for its period. The location shooting in Paris streets represented a move away from studio-bound productions toward more realistic settings. The chase sequences required coordination between camera operators and performers, showing growing sophistication in film technique. The film's editing, particularly during the chase scenes, demonstrates an understanding of rhythm and pacing essential for effective comedy. The use of real Parisian locations also provided authentic production value that enhanced the viewing experience. The film represents the refinement of continuity editing techniques that were becoming standard in French cinema by 1910.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Rembrandt in Rue Lepic' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its theatrical run. The specific musical arrangements used have not been documented, which was typical for short films of this period. Theaters would have employed house musicians or pianists who would select appropriate music to match the on-screen action. For a comedy with chase sequences, the music would likely have been upbeat and lively, possibly incorporating popular songs of the period. The tempo would have increased during chase scenes to heighten the comedic effect. Some theaters might have used sound effects created by live performers to enhance the slapstick elements.

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic chase sequence through the streets of Montmartre as the couple pursues their damaged Rembrandt

- The moment when the woman accidentally sits on the painting, triggering the chaos

- The initial purchase scene on Rue Lepic where the couple believes they've acquired a masterpiece

Did You Know?

- Rue Lepic, where the film is set, was famously home to Vincent van Gogh from 1886 to 1888, adding artistic irony to the Rembrandt theme

- Director Jean Durand was known as one of the pioneers of French slapstick comedy, often referred to as the 'French Mack Sennett'

- The film was produced during the golden age of French cinema when France dominated global film production

- Ernest Bourbon, who starred in the film, was a popular comic actor who often worked with Durand and appeared in numerous Gaumont productions

- The film's theme of art deception was particularly relevant in early 20th century Paris, where art forgery was becoming increasingly sophisticated

- This short film was likely shown as part of a variety program in early cinemas, accompanied by live music and other short subjects

- Gaston Modot, who appears in the film, would later become known for his work in surrealist cinema and collaboration with Luis Buñuel

- The film's slapstick chase sequences were influenced by the popular 'chase film' genre that was extremely popular in the early 1910s

- Berthe Dagmar was one of the few women who regularly appeared in Durand's comedies, often playing the comic relief role

- The film was shot on 35mm film, which was the standard format for professional productions of the era

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of this short film is largely undocumented, as film criticism was still in its infancy in 1910. Reviews of the period typically appeared in trade papers rather than general publications, and many have been lost to time. However, films by Jean Durand were generally well-regarded within the French film industry for their technical proficiency and entertainment value. Modern film historians and archivists who have studied Durand's work recognize this film as representative of his comic style and the broader trends in early French comedy. The film is occasionally referenced in academic discussions of early slapstick cinema and the development of chase sequences in film history.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception in 1910 would have been measured primarily by box office success and theater bookings rather than documented reviews. Films of this era were typically part of variety programs, and their success was judged by their ability to entertain diverse audiences. The slapstick elements and chase sequences would have been particularly appealing to working-class audiences who formed the bulk of early cinema patrons. The recognizable Parisian setting would have added local appeal for French audiences. The film's comedy was visual and universal, requiring no intertitles, making it accessible to international audiences as well, which was important for Gaumont's export market.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Georges Méliès' fantasy films

- Early Pathé comedies

- Mack Sennett's Keystone style (though this predates his most famous work)

- French theatrical comedy traditions

This Film Influenced

- Later French slapstick comedies

- Chase films of the 1910s

- Comedy shorts featuring art world themes

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of 'The Rembrandt in Rue Lepic' is uncertain, which is common for films of this era. Many French films from 1910 have been lost due to the unstable nature of early film stock and the lack of systematic preservation efforts. However, some Jean Durand films have survived in archives, particularly in the Gaumont-Pathé archives and the Cinémathèque Française. If prints exist, they would likely be in 35mm format and possibly incomplete or deteriorated. The film may exist in fragmentary form or as part of compilation reels. Digital restorations, if they exist, would be based on any surviving elements.