The Stranger

"The hunt is on... for the man who murdered millions!"

Plot

Mr. Wilson, a tenacious investigator from the War Crimes Commission, travels to the small town of Harper, Connecticut, under the guise of a clock salesman to track down Franz Kindler, one of the architects of the Holocaust who has escaped justice. Kindler has assumed the identity of Charles Rankin, a respected professor at a local prep school, and is engaged to Mary Longstreet, the daughter of a Supreme Court Justice. As Wilson pieces together clues about Rankin's true identity, he must convince Mary of her fiancé's monstrous past before Kindler can eliminate him and escape once more. The tension escalates as Kindler becomes increasingly desperate to maintain his cover, leading to a dramatic confrontation in the town's clock tower where Wilson must prevent Kindler's escape and bring him to justice.

About the Production

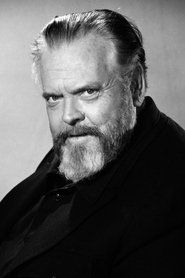

The film was shot in just 36 days, an incredibly short schedule even by 1940s standards. Welles fought with producer Sam Spiegel over creative control, with Spiegel often locking Welles out of the editing room. The famous clock tower sequence was shot using a combination of full-scale sets and matte paintings. The film marked a rare instance where Welles delivered a film on time and under budget, though he later disowned it, calling it 'the worst of my films.'

Historical Background

Released just one year after World War II ended, 'The Stranger' emerged during a period when the world was grappling with the full scope of Nazi atrocities and the hunt for war criminals was headline news. The Nuremberg Trials were underway (1945-1946), making the film's themes particularly resonant. The inclusion of actual concentration camp footage was unprecedented and shocking to American audiences who were only beginning to understand the Holocaust's magnitude. The film tapped into growing Cold War anxieties about hidden enemies within American society, reflecting the emerging paranoia that would define the late 1940s and 1950s. It was also made during Hollywood's post-war golden age, when studios were willing to tackle serious social issues while maintaining commercial appeal.

Why This Film Matters

'The Stranger' holds a unique place in cinema history as the first major Hollywood film to directly address Holocaust perpetrators living in hiding. Its commercial success proved that audiences were ready to confront difficult wartime realities, paving the way for more serious films about World War II. The film's blend of film noir aesthetics with documentary elements created a new template for political thrillers. Its influence can be seen in later films about Nazi hunting, including 'Marathon Man' and 'The Boys from Brazil.' The clock tower finale became an iconic sequence that has been referenced and parodied in numerous films and television shows. The film also demonstrated Orson Welles' ability to create commercially viable art, influencing how studios viewed artistic directors.

Making Of

The production was marked by constant tension between Welles and producer Sam Spiegel. Welles wanted to make a darker, more complex film noir, while Spiegel pushed for a more straightforward thriller. The famous scene where Kindler murders his Nazi associate was shot in one take with Welles performing his own stunts. Welles' innovative use of deep focus and low-angle photography created a sense of paranoia and entrapment throughout the film. The clock tower sequence required extensive planning, with Welles insisting on practical effects rather than the studio's preferred optical printing. Despite the conflicts, the film was completed ahead of schedule, though Welles later claimed Spiegel had recut the film against his wishes, removing several scenes he considered crucial to the story's psychological depth.

Visual Style

Russell Metty's cinematography masterfully blends film noir techniques with documentary realism. The use of deep focus creates a sense of constant surveillance, reflecting Wilson's hunt for Kindler. Low-angle shots emphasize the power dynamics between characters, particularly when Welles' character dominates the frame. The contrast between the idyllic small town settings and the shadowy, claustrophobic interiors creates visual tension throughout. The clock tower sequence showcases innovative camera movement, with sweeping shots that enhance the vertiginous climax. The inclusion of actual concentration camp footage creates a jarring contrast with the polished studio photography, blurring the line between fiction and reality. Metty's use of chiaroscuro lighting in key scenes, particularly during the murder sequence, creates a moral ambiguity that reflects the film's themes.

Innovations

The film's most significant technical achievement was the seamless integration of authentic concentration camp footage into a fictional narrative, a pioneering approach that influenced later documentary-style filmmaking. The clock tower sequence featured innovative use of forced perspective and matte painting to create the illusion of height and danger. Welles employed advanced sound mixing techniques to layer dialogue, ambient noise, and musical score, creating a rich auditory experience. The film's editing, particularly in the climactic sequence, used rapid cross-cutting between multiple perspectives to maximize tension. The production also developed new techniques for creating realistic weather effects, particularly in the film's storm sequences. The use of location shooting combined with studio sets created a hybrid visual style that enhanced the film's realism.

Music

Bronisław Kaper's score combines traditional thriller motifs with subtle musical references to German classical music, creating an ironic commentary on Kindler's cultured facade. The main theme uses a repetitive, clock-like rhythm that echoes the film's central motif of time running out. Kaper incorporates dissonant chords during moments of tension, particularly in scenes involving Kindler's true identity. The score makes effective use of leitmotifs, with distinct musical themes for Wilson's investigation and Kindler's deception. The soundtrack also features diegetic music, including classical pieces performed by characters, which serves to highlight the contrast between civilization and barbarism. The sound design in the clock tower sequence is particularly noteworthy, using the mechanical sounds of the clock to build tension.

Famous Quotes

"What kind of a man are you?" - Mr. Wilson to Charles Rankin, "The kind that must be killed." - Rankin's response

"I think you're a very lucky man, Mr. Wilson. You're going to die." - Franz Kindler

"We're dealing with a megalomaniac. A man who thinks he's God." - Mr. Wilson

"I hate the Nazis. I hate everything they stand for." - Mary Longstreet

"There are no innocent bystanders... what are they doing there in the first place?" - Mr. Wilson

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic clock tower sequence where Kindler attempts to escape while being pursued by Wilson, featuring innovative camera work and stunt work

- The scene where Wilson first shows Mary the concentration camp footage, shattering her innocence about her fiancé

- The murder of Konrad Meinike in the woods, filmed with stark, expressionistic lighting

- The dinner scene where Kindler subtly reveals his Nazi ideology through philosophical discussion

- The final confrontation in the clock mechanism room, where Kindler meets his end among the gears and pendulums

Did You Know?

- This was the first mainstream Hollywood film to include documentary footage of Nazi concentration camps, which was groundbreaking for 1946 audiences

- Orson Welles originally wanted Agnes Moorehead to play Loretta Young's role, but the studio insisted on a more conventionally beautiful leading lady

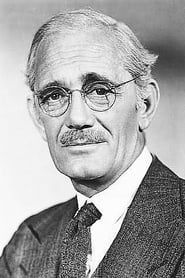

- Edward G. Robinson took the role at a reduced salary because he believed strongly in the film's anti-Nazi message

- The film was Orson Welles' most commercially successful directorial effort during his lifetime

- Welles' character's name, Franz Kindler, was based on a real Nazi war criminal named Franz Stangl

- The clock tower set was so elaborate that it remained standing on the studio lot for years, being reused in other productions

- Loretta Young was deeply religious and initially hesitant to take the role due to its dark themes, but was convinced by the film's moral message

- The film's screenplay was nominated for an Academy Award, making it one of Welles' few films to receive such recognition

- Welles reportedly wrote additional scenes during filming that were never shot due to budget constraints

- The film was banned in several countries, including Franco's Spain, for its political content

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film's timely message and suspenseful execution, with Bosley Crowther of The New York Times calling it 'a taut and absorbing melodrama.' Variety noted its 'unusual subject matter' and praised Robinson's performance as 'excellent.' However, some critics felt the film was too conventional for Welles, with Time magazine suggesting he had 'sold out' to Hollywood conventions. Modern critics have reassessed the film more favorably, with many considering it an underrated masterpiece of film noir. The British Film Institute ranks it among Welles' most accomplished works, praising its visual style and thematic depth. The film's reputation has grown significantly since its initial release, with contemporary scholars highlighting its innovative use of documentary footage within a fictional narrative.

What Audiences Thought

The film was a commercial success, earning over $2.5 million at the box office against its $1 million budget, making it Welles' most profitable film as a director. Audiences were particularly drawn to its timely subject matter and the star power of Edward G. Robinson. The film's suspenseful narrative and shocking revelations kept audiences engaged, with many reporting being deeply affected by the concentration camp footage. The film's success proved that post-war audiences were willing to confront difficult subject matter, influencing Hollywood's approach to wartime themes. Despite Welles' later criticisms of the film, contemporary audiences embraced it as both entertainment and moral education. The film's popularity endured through theatrical re-releases and later television broadcasts, cementing its status as a classic of the thriller genre.

Awards & Recognition

- Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay (nomination)

- National Board of Review Award for Best Film (1946)

- Venice Film Festival - International Award for Best Film (nomination)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Third Man (1949) - similar themes of post-war investigation

- Notorious (1946) - Nazi themes and romantic subplot

- The Maltese Falcon (1941) - noir investigation structure

- Citizen Kane (1941) - Welles' own visual techniques

This Film Influenced

- The Boys from Brazil (1978)

- Marathon Man (1976)

- The Odessa File (1974)

- Apt Pupil (1998)

- Inglourious Basterds (2009)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved by the Library of Congress and was selected for inclusion in the National Film Registry in 2019 for its cultural, historical, and aesthetic significance. A restored version was released on Blu-ray by The Criterion Collection in 2020, featuring a 4K digital restoration from the original camera negative. The original negative is stored at the UCLA Film & Television Archive. The film exists in complete form with no lost scenes, though some deleted footage mentioned in production notes appears to be lost.