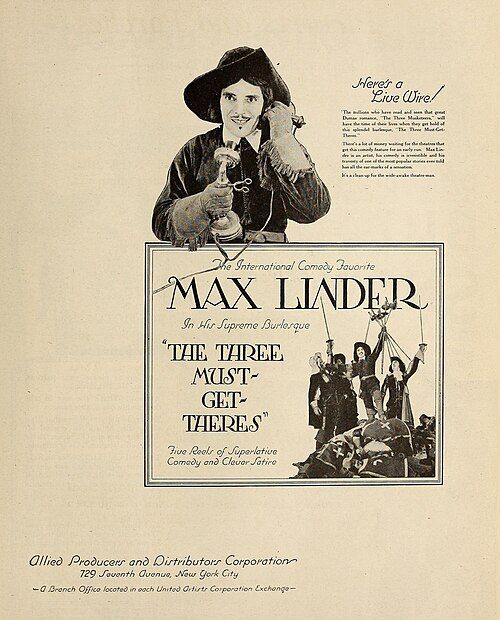

The Three Must-Get-Theres

"A Hilarious Take-Off on the Famous Three Musketeers!"

Plot

Max Linder stars as Max, a young man who travels to Paris to join the King's Musketeers. Upon arrival, he encounters three musketeers (Athos, Porthos, and Aramis) and becomes involved in their adventures. The film parodies the classic Dumas novel with Max's character creating comedic chaos throughout the royal court. Max falls in love with the Queen's lady-in-waiting while attempting to protect the Queen's honor from Cardinal Richelieu's schemes. The climax involves a sword-fighting duel sequence where Max's bumbling heroics save the day.

About the Production

This was Max Linder's first American feature film after moving from France. The film was shot during the transition period when Linder was trying to establish himself in Hollywood. The production faced challenges due to Linder's health issues and his difficulty adapting to the American studio system. The film's title was a play on words, deliberately misspelling 'Musketeers' as 'Must-Get-Theres' for comedic effect.

Historical Background

The early 1920s was a golden age for swashbuckling films, with Douglas Fairbanks dominating the genre with hits like 'The Mark of Zorro' (1920) and 'The Three Musketeers' (1921). This film emerged during the post-WWI period when European filmmakers were increasingly migrating to Hollywood. The film industry was consolidating into the studio system, and comedians were becoming major box office draws. The Roaring Twenties were beginning, and audiences craved both escapism and sophisticated entertainment. The film also reflects the cultural exchange happening between European and American cinema, with Linder representing the more refined European comedic tradition attempting to find a place in the more robust American market.

Why This Film Matters

The Three Must-Get-Theres represents an important cross-cultural moment in cinema history, showcasing how European comedy styles were adapted for American audiences. It demonstrated that parody was already becoming a sophisticated cinematic art form in the silent era. The film is historically significant as one of the earliest examples of a major international star attempting to transition between film industries. It also shows how literary adaptations were being immediately parodied, indicating the speed with which popular culture was being processed and reinterpreted in early cinema. Linder's work influenced later comedians who would blend sophistication with physical comedy, including elements that can be seen in the work of Harold Lloyd and even in later films by directors like Mel Brooks.

Making Of

Max Linder, already a superstar in European cinema, moved to America in 1921 seeking new opportunities. This film was his ambitious attempt to conquer Hollywood with his sophisticated brand of comedy, which contrasted with the more slapstick style popular in American films. Linder brought his own production team from France and insisted on creative control. The filming process was marked by cultural clashes between European and American working methods. Linder's perfectionism led to multiple retakes of scenes, especially the sword fights, which he wanted to be both technically impressive and comedically timed. The production utilized some of the same sets and costumes that had been used in other swashbuckling films of the era, demonstrating Hollywood's resourcefulness. Linder's health problems, including the aftereffects of poison gas exposure during WWI, sometimes forced production delays.

Visual Style

The cinematography, credited to Harry F. Millarde, employed the dramatic lighting techniques popular in swashbuckling films of the era. The film used deep shadows and high contrast lighting during the sword fight sequences to enhance the dramatic tension before subverting it with comedy. Tracking shots were used during chase sequences, and the camera work during the duel scenes was particularly dynamic for its time. The cinematography successfully balanced the epic feel of swashbuckling films with the intimate moments needed for Linder's facial comedy, which was crucial to his performance style.

Innovations

The film featured innovative use of camera movement during sword-fighting sequences, employing techniques that enhanced both the action and the comedy. The production used multiple camera setups for complex scenes, which was still relatively uncommon in 1922. The film's intertitles were particularly sophisticated, using visual gags and typography that complemented the on-screen action. The sword-fighting choreography was technically impressive while maintaining comedic timing, requiring precise coordination between actors and camera. The film also utilized some early special effects techniques for the more fantastical elements of the parody.

Music

As a silent film, it would have been accompanied by live musical performances in theaters. The original score was composed by William Axt and included adaptations of popular classical pieces along with original compositions. The music ranged from dramatic orchestral pieces during sword fights to lighter, more whimsical melodies for comedic scenes. In some larger theaters, the film was accompanied by full orchestras, while smaller venues used piano or organ accompaniment. Modern restorations have been scored with period-appropriate music by silent film accompanists.

Famous Quotes

Max: 'I may not be the best musketeer, but I'm certainly the most persistent!'

Cardinal Richelieu: 'This young man is either a genius or a fool... I suspect both.'

Athos: 'One for all and all for lunch!'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where Max arrives in Paris and comically misunderstands the musketeers' motto

- The sword-fighting duel where Max accidentally defeats multiple opponents through sheer luck

- The palace scene where Max attempts to serve the Queen while creating chaos in the royal court

- The climactic rescue sequence featuring elaborate stunt work and comedic timing

Did You Know?

- Max Linder was one of the highest-paid and most famous comedians in the world before Charlie Chaplin, with a salary that rivaled Chaplin's in the early 1910s

- The film was Linder's attempt to capitalize on the popularity of swashbuckling films that were dominating cinema in the early 1920s

- Linder's character 'Max' was his signature persona that he developed in French cinema before bringing it to America

- The film featured elaborate sword-fighting sequences that were meticulously choreographed for comedic effect rather than authenticity

- Bull Montana, who played one of the musketeers, was a former professional wrestler turned actor known for his imposing physical presence

- The film's sets were designed to mimic the lavish productions of Douglas Fairbanks' swashbucklers but on a more modest budget

- Linder personally supervised the intertitles to ensure the humor translated well to American audiences

- The film was released just before Linder's tragic suicide attempt and subsequent death in 1925

- Original prints featured hand-tinted color sequences for certain dramatic moments

- The film's French title was 'Les Trois Mousquetaires' when shown in European markets

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised Linder's performance and the film's clever parody elements, though some found it too European in sensibility for American audiences. Variety noted that 'Linder brings his usual continental charm to the swashbuckling genre with delightful results.' The New York Times appreciated the sophisticated humor but questioned whether American audiences would fully embrace Linder's style. Modern critics and film historians recognize the film as an important work in the development of cinematic parody and as a testament to Linder's talent. The film is now considered a significant artifact of silent comedy, particularly for its role in the transatlantic exchange of comedic styles.

What Audiences Thought

The film achieved moderate success in major urban areas but struggled in smaller American markets where Linder was less known. European audiences, particularly in France where Linder remained extremely popular, responded more enthusiastically to the film. The comedy was appreciated by those familiar with both the original Three Musketeers story and Linder's previous work. Some American audiences found the humor more subtle than the slapstick they were accustomed to from comedians like Chaplin and Keaton. The film developed a cult following among silent film enthusiasts in later years, with many considering it an underrated gem of the era.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Three Musketeers by Alexandre Dumas

- Douglas Fairbanks' swashbuckling films

- French theatrical comedy traditions

- European literary adaptations

This Film Influenced

- The Pink Panther series (parody elements)

- Airplane! (parody technique)

- The Princess Bride (swashbuckling comedy)

- Robin Hood: Men in Tights (literary parody)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is partially preserved with some scenes missing or damaged. A restored version exists combining elements from various international prints. The film is held in the collections of several archives including the Library of Congress and the French Cinémathèque. Some original nitrate footage has been preserved and digitized, though the complete original version may be lost.