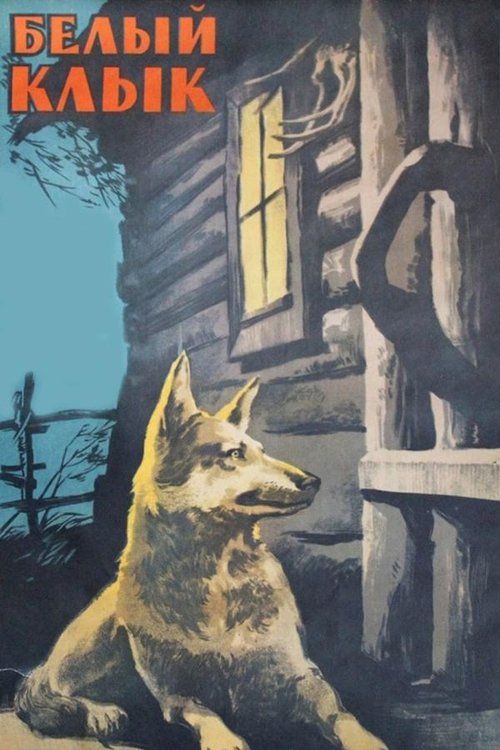

The White Fang

Plot

The film follows the life journey of White Fang, a wolf-dog hybrid born in the harsh Yukon wilderness. After his mother is killed, the young cub is taken in by an Indian boy named Grey Beaver, who raises him with both affection and harshness, teaching him survival in the wild. When Grey Beaver falls into debt at a settlement, he sells White Fang to the cruel Beauty Smith, a saloon owner who exploits the animal's ferocity in brutal dog fights, transforming him into a vicious fighting machine. The turning point comes when White Fang is nearly killed in a fight against a bulldog but is rescued by the kind-hearted mining engineer Weedon Scott, whose patience and compassion gradually rehabilitate the traumatized animal. Through Scott's gentle care, White Fang learns to trust humans again and ultimately saves his new master's life, completing his transformation from a wild beast to a loyal companion.

About the Production

The film was one of the first major Soviet adaptations of an American author's work after WWII. The production faced significant challenges in sourcing and training animals for the film, particularly the wolf-dogs that portrayed White Fang at different ages. Director Aleksandr Zguridi, known for his nature documentaries, insisted on using real animals rather than relying on trick photography, resulting in months of animal training before principal photography could begin.

Historical Background

The film was produced and released in the immediate aftermath of World War II, during a period of reconstruction and cultural redefinition in the Soviet Union. 1946 marked the beginning of the Cold War, making the adaptation of an American author's work particularly significant. The Soviet cultural establishment, under Stalin's direction, was simultaneously promoting Soviet values while carefully selecting foreign works that could be ideologically acceptable. Jack London's socialist leanings and his depiction of class struggle and the exploitation of nature made his work suitable for Soviet adaptation. The film's themes of redemption through kindness and the critique of cruelty (represented by Beauty Smith's capitalist exploitation) aligned well with Soviet ideology. The production also reflected the Soviet Union's post-war emphasis on educational and morally uplifting cinema, particularly for younger audiences.

Why This Film Matters

'The White Fang' holds a unique place in Soviet cinema history as one of the earliest major adaptations of American literature during the Cold War era. The film's success demonstrated that carefully selected Western works could be adapted to serve Soviet cultural and educational purposes. It helped establish Jack London as one of the few American authors widely read and respected in the Soviet Union, alongside Mark Twain and Ernest Hemingway. The film also influenced Soviet approaches to animal-centered narratives, paving the way for later nature films and animal stories. Its emphasis on the moral education of young viewers through the redemption narrative became a template for subsequent Soviet family films. The movie's technical achievements in animal filming were studied by Soviet filmmakers for years and influenced the development of the Soviet nature documentary tradition.

Making Of

The production of 'The White Fang' was remarkable for its time, particularly in its approach to animal filming. Director Aleksandr Zguridi brought his documentary expertise to the feature film, insisting on authentic animal behavior rather than relying on the common practice of using taxidermy animals or obvious puppets. The film's animal trainer, Vladimir Durov (from the famous Durov animal theater dynasty), spent nearly a year working with the wolf-dogs before filming began. The most challenging scenes involved the dog fights, which were carefully choreographed to appear brutal while ensuring no harm came to the animals. The production team built special sets with hidden barriers and used camera angles to create the illusion of vicious combat. The wilderness sequences were filmed during the harsh Russian winter, with the cast and crew enduring extreme temperatures to achieve the authentic Yukon atmosphere. The film's post-production was also notable for its innovative use of sound design to create the wilderness ambiance.

Visual Style

The cinematography, led by Boris Volchek, was groundbreaking for its time in capturing animal behavior and wilderness landscapes. The film employed innovative techniques including specially designed low-angle cameras to film from the animals' perspectives and long lenses for wildlife sequences without disturbing the animals. The winter scenes utilized natural light to create an authentic, harsh atmosphere that mirrored the Yukon setting. The fight sequences used rapid editing and strategic camera placement to create tension while maintaining the illusion of real combat. The contrast between the cold, blue-toned wilderness scenes and the warmer, more intimate moments with Weedon Scott was achieved through careful lighting and color grading techniques that were advanced for Soviet cinema of the 1940s.

Innovations

The film's most significant technical achievement was its pioneering approach to filming animal sequences. The production team developed custom camera rigs that could be mounted on animals for point-of-view shots, a technique that was revolutionary for the 1940s. They also created specialized training methods that allowed for complex animal behaviors to be captured on film without the use of force or cruelty. The fight sequences employed innovative editing techniques and careful choreography that created realistic combat without endangering the animals. The film also utilized early forms of process photography for some wilderness scenes, allowing the actors to be convincingly integrated with the harsh outdoor environments. The sound recording techniques for capturing natural wilderness sounds were particularly advanced for Soviet cinema of the era.

Music

The musical score was composed by Nikita Bogoslovsky, one of the Soviet Union's most prominent film composers. Bogoslovsky created a leitmotif-based score that evolved with White Fang's character journey - from wild, dissonant themes representing his feral nature, to increasingly melodic and harmonious passages as he experiences kindness and redemption. The soundtrack made innovative use of folk instruments, particularly in scenes with the Indian characters, while incorporating more traditional orchestral arrangements for the settlement sequences. The sound design was particularly notable for its naturalistic approach to animal vocalizations and wilderness ambient sounds, a reflection of director Zguridi's documentary background. The main theme became quite popular and was later arranged for concert performance by Soviet orchestras.

Famous Quotes

There is an instinct in a dog to fight, and an instinct in a man to be kind.

The wild is still in him, but now there is something else too - love.

A dog's loyalty is earned, not bought.

In the wilderness, only the strong survive, but only the kind truly live.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing White Fang's birth in the wolf den, filmed with remarkable intimacy and naturalism

- The brutal dog fight scene where White Fang faces the bulldog, choreographed with stunning tension and emotional impact

- The rescue scene where Weedon Scott saves White Fang from the fight, marking the turning point of the narrative

- The gradual rehabilitation sequence showing Scott's patient efforts to win the animal's trust

- The climactic scene where White Fang saves Scott from danger, completing his transformation from wild beast to loyal companion

Did You Know?

- This was the first Soviet film adaptation of a Jack London novel, despite London's popularity in the USSR

- Director Aleksandr Zguridi was primarily known as a documentary filmmaker specializing in nature films, which influenced the realistic animal sequences

- The film used multiple dogs to portray White Fang at different ages, all carefully trained for months before filming

- The dog fight scenes were controversially realistic, though no animals were actually harmed during filming

- The film was released during Stalin's post-war cultural crackdown, making the choice of an American author's work notable

- Oleg Zhakov, who played Weedon Scott, was one of the most respected actors in Soviet cinema at the time

- The wilderness scenes were filmed in Crimea, which was chosen for its resemblance to the Yukon landscape

- The film's success led to increased interest in Jack London's works throughout the Soviet Union

- The original Russian title was 'Белый Клык' (Belyy Klyk), which translates directly to 'White Fang'

- The film's production began in 1944 but was delayed due to wartime resource shortages

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film for its moral message and technical achievements, particularly in the realistic portrayal of animals. Pravda highlighted the film's educational value and its faithful adaptation of London's themes. Western critics, when the film was occasionally shown at international festivals, were surprised by the quality of the Soviet production and its sensitive handling of the source material. Modern film historians view the adaptation as a significant achievement in Soviet cinema, noting how it successfully navigated the ideological requirements of the time while creating an emotionally resonant work. Critics particularly praise Zguridi's documentary-style approach to the nature sequences and the film's avoidance of heavy-handed propaganda, instead focusing on universal themes of kindness and redemption.

What Audiences Thought

The film was enormously popular with Soviet audiences, particularly children and families. It became one of the most attended films of 1946-1947 in Soviet theaters. Many viewers wrote letters to the film studios expressing their emotional connection to White Fang's story and praising the film's message about the importance of kindness to animals. The film's success led to increased demand for Jack London's books in Soviet libraries and bookstores. In the decades following its release, 'The White Fang' became a staple of Soviet television programming during holidays and school vacations. Even today, it remains a beloved classic among older generations who grew up with the film, often cited as a formative cinematic experience that taught lessons about compassion and the relationship between humans and nature.

Awards & Recognition

- Stalin Prize, Second Degree (1947) - For outstanding achievement in cinema

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Jack London's novel 'White Fang' (1906)

- Soviet socialist realist cinema tradition

- Soviet nature documentary movement

- Classical Hollywood animal films of the 1930s-40s

This Film Influenced

- The White Fang (1973 Soviet animated version)

- White Fang (1991 Disney film)

- Numerous Soviet nature films of the 1950s-60s

- The Call of the Wild adaptations

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved in the Gosfilmofond of Russia, the state film archive. A restored version was released in the 1990s as part of a Soviet classics restoration project. The original camera negative survives in good condition, though some elements show minor deterioration typical of films from the 1940s. The film is regularly screened at retrospectives of Soviet cinema and has been released on DVD in Russia with English subtitles for international audiences.