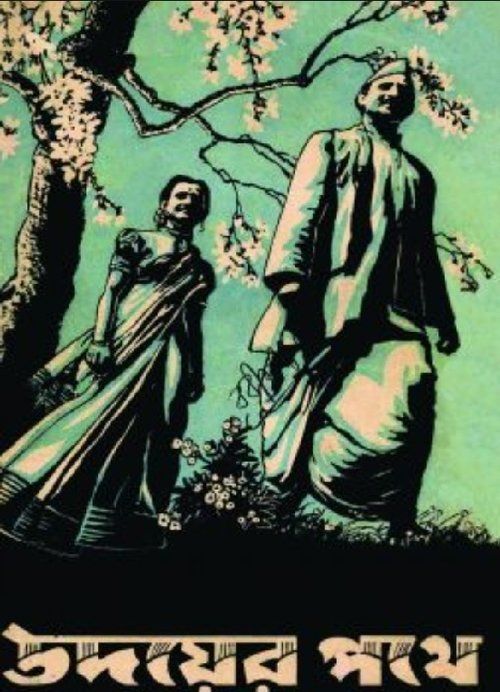

Udayer Pathey

"The path to dawn begins with the courage to challenge darkness"

Plot

Udayer Pathey follows the journey of Anup, a talented but struggling writer who works as a speechwriter for the wealthy industrialist Prasanna Babu. After losing his job due to ideological differences, Anup dedicates himself to completing his novel, which he hopes will express his socialist ideals and expose the exploitation of the working class. When Prasanna Babu discovers the manuscript and steals it, publishing it under his own name, Anup is devastated but ultimately finds purpose in joining the growing socialist movement. The film explores Anup's transformation from an individual artist to a political activist, while also depicting the romantic relationship with his beloved Kalyani, who supports his ideals. Set against the backdrop of pre-independence India, the narrative culminates with Anup embracing collective action over individual artistic achievement, symbolizing the broader social awakening of the era.

About the Production

Filmed during the height of World War II, which created significant production challenges including limited film stock resources and wartime restrictions. The film was shot on location in Calcutta, capturing the authentic urban landscape and social conditions of the 1940s. Bimal Roy, making his directorial debut, brought his documentary background to the realistic portrayal of working-class life. The production team faced censorship challenges due to the film's overt socialist themes and critique of industrial capitalism, requiring careful navigation of British colonial censorship boards.

Historical Background

Udayer Pathey was created during a pivotal moment in Indian history, as the independence movement gained momentum and socialist ideas spread among intellectuals. The film emerged in 1944, during the final years of British colonial rule, when India was experiencing significant social and political upheaval. The Bengal Famine of 1943, which claimed millions of lives, had profoundly affected the region's consciousness and heightened awareness of social inequality and economic exploitation. The film's release coincided with the Quit India Movement and growing labor unrest in industrial centers like Calcutta. This period also saw the rise of leftist cultural movements, including the Indian People's Theatre Association, which sought to use art as a tool for social change. The film's critique of industrial capitalism and advocacy for socialist solutions reflected the growing influence of Marxist thought among Indian intellectuals and artists during the 1940s.

Why This Film Matters

Udayer Pathey marked a significant shift in Indian cinema toward social realism and political consciousness, establishing a new paradigm for films addressing contemporary social issues. The film's success demonstrated that Indian audiences were ready for mature, politically engaged cinema that went beyond entertainment to address pressing social concerns. It influenced an entire generation of filmmakers, including Satyajit Ray, who would later revolutionize Indian cinema with similar realist approaches. The film's blend of personal drama with political commentary created a template for socially relevant cinema that continues to influence Indian filmmakers today. Its portrayal of the artist's social responsibility resonated with post-independence India's nation-building efforts and the debate about art's role in society. The film also contributed to the development of Bengali cinema as a distinct artistic movement separate from mainstream Hindi cinema, establishing Calcutta as a center for serious, artistic filmmaking.

Making Of

Bimal Roy, who had previously worked as a cinematographer, brought a distinctive visual realism to his directorial debut that would become his signature style. The production took place during the Bengal Famine of 1943, which deeply influenced the film's social consciousness and realistic depiction of poverty. Roy insisted on using natural lighting and location shooting to capture the authentic atmosphere of Calcutta's working-class neighborhoods. The cast, primarily drawn from Bengali theater, underwent extensive preparation to understand the political ideologies their characters represented. Screenwriter Jogen Chowdhury adapted the story from his own experiences with political activism and literary circles in 1940s Bengal. The film's controversial socialist themes led to heated debates within New Theatres about the commercial viability of such overt political content. Despite these challenges, the studio's management supported Roy's artistic vision, recognizing the changing social consciousness of Indian audiences during the independence movement.

Visual Style

Sudhin Majumdar's cinematography in Udayer Pathey broke new ground for Indian cinema through its use of natural lighting, location shooting, and documentary-style visual approach. The camera work emphasized realistic textures and authentic urban environments, moving away from the artificial studio look common in Indian films of the era. Majumdar employed deep focus techniques to capture the social dynamics within scenes, allowing multiple planes of action that reflected the film's themes of social interconnectedness. The visual style incorporated elements of German Expressionism and Soviet montage, particularly in sequences depicting industrial labor and political rallies. The cinematography used contrast effectively to highlight the divide between wealth and poverty, with the industrialist's world shown in bright, polished surfaces while working-class areas were captured in grittier, more textured visuals. The film's visual language established a template for Indian social realism that would influence generations of filmmakers.

Innovations

Udayer Pathey pioneered several technical innovations in Indian cinema, particularly in its use of synchronous sound recording on location, which was rare for Indian films of the 1940s. The film's sound design emphasized natural ambient sounds of urban Calcutta, creating an authentic auditory environment that complemented its visual realism. The editing style, influenced by Soviet cinema, used montage sequences effectively to convey political ideas and social transformation without resorting to didactic dialogue. The film's production design successfully recreated the contrasting worlds of industrial wealth and working-class poverty using real locations rather than studio sets. The technical team developed new techniques for filming in Calcutta's crowded urban environments, including innovative camera mounting solutions for shooting in narrow lanes and factory spaces. The film's post-production processes, particularly in sound mixing and dubbing, set new standards for technical quality in Indian cinema.

Music

The film's music was composed by Raichand Boral, one of the pioneers of film music in Indian cinema, with lyrics by Jogen Chowdhury. The soundtrack blended traditional Bengali musical forms with contemporary themes, creating songs that advanced the narrative while commenting on social issues. The music avoided the escapist tendencies common in Indian film songs of the period, instead using melodies that reflected the characters' emotional states and political awakening. The film featured several songs that became popular for their social relevance rather than just their musical appeal, including numbers that directly addressed themes of labor rights and social justice. The soundtrack's integration with the narrative was innovative for its time, with songs emerging naturally from story situations rather than appearing as disconnected entertainment segments. The musical arrangements incorporated both Western and Indian instruments, reflecting the cultural synthesis characteristic of urban Bengal in the 1940s.

Famous Quotes

When the pen becomes a weapon, truth becomes its ammunition

The dawn doesn't break for those who sleep through the night of oppression

My novel was not just words on paper; it was the voice of those who couldn't speak

In the factory of progress, workers are the fuel that burns to light others' way

To steal a story is to steal the soul of its people

Politics is not separate from life; it is the shape we give to our collective dreams

When art serves only the artist, it becomes a luxury; when it serves the people, it becomes a revolution

The road to dawn is paved with the stones of yesterday's struggles

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing Anup typing furiously in his modest room, with shadows dancing on the walls as he crafts speeches for the industrialist

- The confrontation scene where Anup discovers his stolen manuscript published under Prasanna Babu's name, his face moving from disbelief to righteous anger

- The factory montage sequence showing workers' faces intercut with machinery, creating a powerful visual metaphor for human exploitation

- The final rally scene where Anup addresses workers, the camera rising slowly to show the growing crowd symbolizing collective awakening

- The intimate conversation between Anup and Kalyani by the Hooghly River, where personal love and political commitment merge

- The scene where Anup burns his early romantic poems, symbolizing his transformation from individual artist to political activist

Did You Know?

- This was Bimal Roy's directorial debut, launching one of Indian cinema's most influential careers

- The film was simultaneously made in Hindi as 'Hamrahi' with a different cast, but the Bengali version became more acclaimed

- New Theatres, the production company, was one of India's most prestigious film studios of the 1930s-40s

- The film's title translates to 'On the Road to Dawn' in English, symbolizing the journey toward social awakening

- Radhamohan Bhattacharya, who played Anup, was a renowned stage actor before appearing in films

- The film's realistic style was revolutionary for Indian cinema at the time, departing from theatrical traditions

- Cinematographer Sudhin Majumdar's work on this film influenced the visual language of Indian social realism

- The film was one of the first Indian movies to explicitly address class conflict and socialist ideology

- Despite its political themes, the film was approved by British censors, possibly due to its artistic merit

- The manuscript theft subplot was based on real incidents of intellectual property exploitation common in colonial India

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised Udayer Pathey for its bold social message and realistic approach, with many calling it a landmark achievement in Indian cinema. The film was particularly lauded for breaking away from the theatrical traditions that dominated Indian filmmaking and introducing a more naturalistic style of acting and storytelling. Critics noted Bimal Roy's assured directorial hand, especially remarkable for a debut film, and praised his ability to balance political content with emotional drama. The film's cinematography and use of real locations were highlighted as revolutionary for Indian cinema of the period. Modern critics and film scholars regard Udayer Pathey as a precursor to the Indian New Wave cinema of the 1950s-60s, recognizing its influence on filmmakers like Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak. The film is now studied in film schools as an early example of socially committed cinema in India and is frequently cited in scholarly works about Indian political cinema.

What Audiences Thought

Udayer Pathey resonated strongly with urban, educated audiences in Bengal, particularly among the growing middle class and intellectual circles sympathetic to nationalist and socialist ideas. The film's realistic depiction of working-class struggles and its critique of economic inequality struck a chord with audiences experiencing the hardships of World War II and the Bengal Famine. Despite its serious themes and political content, the film found commercial success, proving that Indian audiences were receptive to socially relevant cinema. The romantic subplot and the personal journey of the protagonist helped make the political themes accessible to mainstream viewers. The film generated significant discussion in newspapers and literary magazines about the role of cinema in addressing social issues. Audience reactions were particularly strong in Calcutta, where the film's urban setting and industrial themes felt immediate and relevant to viewers' daily lives.

Awards & Recognition

- Bengal Film Journalists' Association Award for Best Film (1944)

- Bengal Film Journalists' Association Award for Best Director - Bimal Roy (1944)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Soviet socialist realist cinema

- German Expressionist visual techniques

- Bengali literary traditions of social criticism

- Indian People's Theatre Association movement

- British documentary film movement

- Italian neorealism (predecessor influences)

- Marxist literary theory

- Bengali Renaissance cultural legacy

This Film Influenced

- Do Bigha Zamin (1953)

- Pather Panchali (1955)

- Madhumati (1958)

- Sujata (1959)

- Bandini (1963)

- Mahanagar (1963)

- Mrigayaa (1976)

- Manikchandra Bandyopadhyay's later works

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is partially preserved with some degradation of the original print elements. The National Film Archive of India holds surviving copies, though some scenes show signs of nitrate deterioration common in films of this era. Restoration efforts have been undertaken by film preservationists, but complete restoration remains challenging due to missing footage and audio elements. The Bengali version is better preserved than the Hindi version 'Hamrahi', of which only fragments survive. Film scholars have been working to reconstruct missing portions using production stills and contemporary reviews. The film's historical significance has led to increased preservation efforts in recent years, with international film archives collaborating on conservation projects.