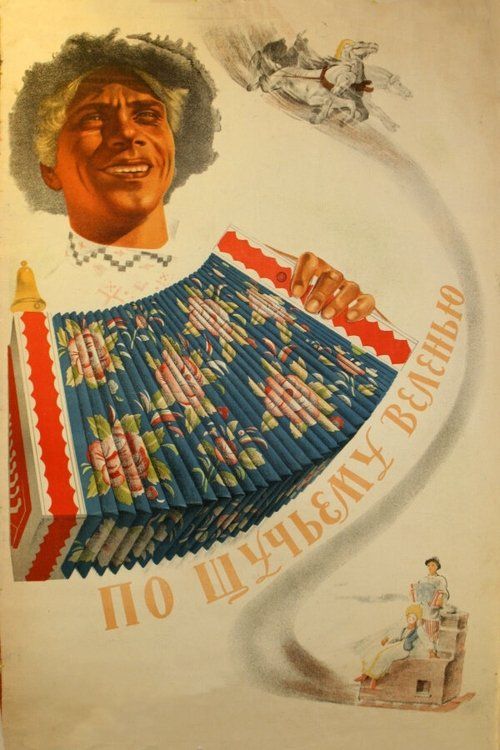

Wish upon a Pike

"The magical tale where a fool's wish becomes reality"

Plot

The film follows Emelya, a lazy but good-hearted peasant boy known as 'the Fool,' who lives with his family in a Russian village. One winter day while ice fishing, Emelya catches a magical talking pike who begs for its life and promises to grant him any wish if he releases it. Emelya takes the pike home but forgets to feed it, so the pike escapes, leaving behind its magical powers that now obey Emelya's commands. Using his newfound ability to make anything happen by simply saying 'by the pike's command,' Emelya navigates various adventures including winning the affection of the Tsar's daughter, outsmarting nobles, and ultimately proving that even a 'fool' can possess wisdom and goodness. The film culminates in Emelya's transformation from a simple village boy to a respected member of society, all while maintaining his humble nature and helping those around him.

About the Production

This was one of the first Soviet fantasy films and director Aleksandr Rou's debut feature. The film faced initial skepticism from Soviet authorities who were wary of fantasy elements, but it was approved due to its folk tale origins and positive moral message. Special effects were primitive by modern standards but innovative for 1938 Soviet cinema, including early matte paintings and stop-motion techniques for magical sequences.

Historical Background

Produced in 1938, 'Wish upon a Pike' emerged during a complex period in Soviet history. The Great Purge was at its height, and the Soviet film industry was under intense ideological scrutiny. Stalin's cultural policies favored socialist realism, which typically depicted realistic stories about workers and peasants. However, the Soviet leadership also recognized the value of traditional folk culture in promoting Soviet identity, especially for children. The film's release came just before World War II, during a period when the Soviet government was increasingly emphasizing Russian nationalism and folk traditions as part of its cultural policy. This context explains why a fantasy film based on folk tales could be approved and even celebrated - it served both educational purposes by preserving cultural heritage and ideological purposes by showing the triumph of the common person (Emelya) over aristocracy (the Tsar).

Why This Film Matters

'Wish upon a Pike' holds a unique place in cinema history as the film that essentially created the Soviet fantasy genre. It proved that films with magical elements could be both commercially successful and ideologically acceptable within the Soviet system. The movie established many conventions that would define Russian and Soviet fantasy cinema for decades, including the use of folk tales as source material and the emphasis on moral lessons. The character of Emelya became an archetypal figure in Soviet popular culture - the 'holy fool' who possesses hidden wisdom and magical powers. The film's success led to a golden age of Soviet fantasy films in the 1940s-1970s, with director Rou becoming the genre's master. The phrase 'по щучьему веленью' entered the Russian language as a common expression meaning 'as if by magic.' The film also demonstrated how traditional culture could be adapted for modern cinematic purposes without losing its essential character, influencing how folk tales would be treated in cinema worldwide.

Making Of

The production of 'Wish upon a Pike' marked a significant milestone in Soviet cinema as one of the first full-length fantasy films produced in the country. Director Aleksandr Rou, who had previously worked as an assistant director, fought hard to get the project approved by Soviet film authorities who were initially skeptical of fantasy elements. The filming took place primarily at Mosfilm Studios during the summer of 1938, with the winter scenes shot using artificial snow and ice created on soundstages. The special effects team, led by cinematographer Fyodor Novitsky, developed innovative techniques for the magical sequences, including early forms of matte painting and forced perspective photography. The cast underwent extensive preparation, with Pyotr Savin studying Russian folk traditions and dialects to accurately portray Emelya. The film's score, composed by Lev Shvarts, incorporated traditional Russian folk melodies arranged for full orchestra, creating a musical bridge between classical film scoring and folk traditions.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Fyodor Novitsky was considered groundbreaking for its time, particularly in how it handled the fantasy elements. Novitsky employed innovative techniques including forced perspective to make characters appear different sizes, early matte paintings for magical backgrounds, and creative use of lighting to distinguish between the mundane world and magical sequences. The film's visual style combined realistic depictions of Russian peasant life with fantastical elements, creating a seamless blend of reality and magic. The winter scenes were particularly notable for their atmospheric quality, achieved through careful lighting and the use of artificial snow. The cinematography also emphasized the contrast between the humble peasant world and the opulent Tsar's palace, using composition and lighting to reinforce the film's themes. Novitsky's work influenced the visual language of subsequent Soviet fantasy films, establishing a distinctive aesthetic that balanced realism with magical elements.

Innovations

For 1938 Soviet cinema, the film featured several technical innovations. The special effects team developed new techniques for creating magical transformations, including early forms of stop-motion animation and in-camera effects. The talking pike sequence used a combination of puppetry and careful editing to create the illusion of speech. The film also employed advanced matte painting techniques for the magical backgrounds and settings. The production team created sophisticated practical effects for scenes involving magical movement and transformation, using wires, pulleys, and carefully choreographed camera movements. The sound recording techniques used for the magical elements were also innovative for the time, creating otherworldly audio effects through experimental manipulation of recordings. The film's success in creating believable fantasy elements with limited technology demonstrated the creativity and resourcefulness of Soviet filmmakers during this period.

Music

The musical score was composed by Lev Shvarts, who drew heavily from Russian folk traditions while employing classical orchestral techniques. The soundtrack features several traditional Russian folk songs and melodies, arranged for full orchestra with choral elements. The main theme, based on a traditional Russian folk tune, became instantly recognizable to Soviet audiences. The music plays a crucial role in establishing the film's fairy tale atmosphere, with different leitmotifs representing Emelya's magic, the pike, and various characters. The score was innovative in how it blended authentic folk instrumentation with symphonic arrangements, creating a sound that was both traditional and modern for its time. The soundtrack was recorded using the best available technology of 1938, and while the audio quality shows its age, the musical arrangements remain effective. The film's success led to Shvarts becoming one of the most sought-after composers for Soviet fantasy and children's films.

Famous Quotes

По щучьему веленью, по моему хотенью! (By the pike's command, by my desire!)

Не хочу работать, хочу жениться! (I don't want to work, I want to get married!)

Вот так-то, братцы мои! (That's how it is, my brothers!)

Эх, хорошо-то как! (Oh, how wonderful it is!)

Memorable Scenes

- The ice fishing sequence where Emelya first catches the magical pike

- Emelya's first use of magic to make the sleigh move by itself

- The scene where Emelya uses his powers to win the archery contest

- The transformation sequence where Emelya becomes handsome and wins the princess

- The final scene where Emelya uses his magic to help the village

Did You Know?

- The film is based on four different Russian folk tales, primarily 'Emelya the Fool' but incorporating elements from other traditional stories

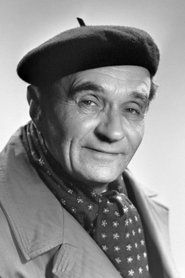

- Director Aleksandr Rou would become known as the master of Soviet fantasy films, directing many more fairy tale adaptations throughout his career

- The talking pike was created using a combination of practical effects and puppetry, considered quite advanced for Soviet cinema in 1938

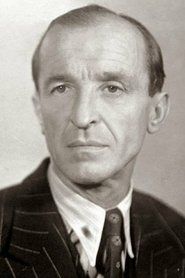

- Pyotr Savin, who played Emelya, was only 19 years old when he starred in the film, despite playing a character meant to be younger

- The film was one of the first children's films produced by the newly created Soyuzdetfilm studio, which specialized in movies for young audiences

- Georgi Millyar, who played multiple roles including the Tsar, became a regular collaborator with Rou, appearing in nearly all his fantasy films

- The magical phrase 'по щучьему веленью' (by the pike's command) became a popular cultural reference in the Soviet Union

- The film was nearly banned during the Stalin era for promoting 'superstition' but was saved by its folk tale origins and educational value

- Costumes were designed based on extensive research of traditional Russian peasant clothing from the 19th century

- The ice fishing sequence was filmed during an actual Moscow winter, with the cast working in sub-zero temperatures

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film for its faithful adaptation of folk tales and its technical achievements in creating magical effects. Pravda, the official Soviet newspaper, called it 'a triumph of Soviet cinema that brings our rich folk heritage to life for new generations.' Western critics who saw the film during rare screenings in the 1940s and 1950s were often surprised by the quality of Soviet fantasy filmmaking, with Variety noting its 'charming simplicity and technical competence.' Modern film historians view 'Wish upon a Pike' as a groundbreaking work that successfully navigated the complex requirements of Soviet censorship while creating an entertaining and artistically significant film. Critics today particularly praise the film's preservation of Russian folk traditions and its influence on subsequent fantasy cinema in both the Soviet Union and internationally.

What Audiences Thought

The film was enormously popular with Soviet audiences upon its release, especially with children and families. It became one of the most attended films of 1938-1939 in Soviet theaters, with many children returning to see it multiple times. The character of Emelya resonated particularly strongly with viewers, who saw in him a representation of the common person's potential for greatness. The film developed a cult following that persisted throughout the Soviet era, with annual television broadcasts becoming holiday traditions for many families. Even decades after its release, Soviet audiences remembered the film fondly, and it was frequently referenced in popular culture. The film's popularity extended beyond the Soviet Union to other Eastern Bloc countries, where it was widely distributed and beloved. Modern Russian audiences continue to hold the film in high regard, with it regularly appearing in lists of the greatest Russian films of all time.

Awards & Recognition

- Stalin Prize, Second Class (1941)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Russian folk tales

- Traditional Slavic mythology

- Alexander Pushkin's fairy tale adaptations

- Earlier Soviet realist films

- European fairy tale cinema of the 1930s

This Film Influenced

- The Frog Princess (1954)

- Morozko (1964)

- Jack Frost (1964)

- Vasilisa the Beautiful (1939)

- The Kingdom of Crooked Mirrors (1963)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved in the Gosfilmofond Russian State Archive and has undergone digital restoration. Multiple restored versions exist, including a 2004 digital remaster that cleaned up both video and audio elements. The original camera negatives are believed to be intact, making future restorations possible.