Kenji Mizoguchi

Director

About Kenji Mizoguchi

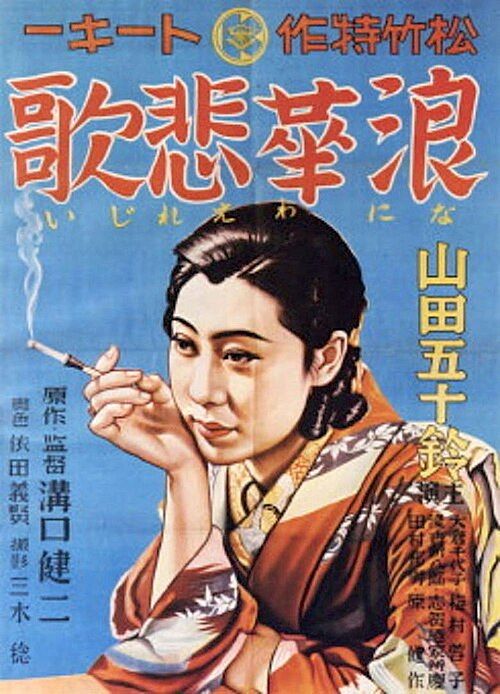

Kenji Mizoguchi was one of Japan's most acclaimed film directors, renowned for his masterful long takes, fluid camera movements, and profound empathy for his female protagonists. Born into poverty in Tokyo, he began his career in the early 1920s during the silent era, initially working as an actor and scriptwriter before transitioning to directing. Mizoguchi's films consistently explored themes of social injustice, the oppression of women, and the clash between tradition and modernity in Japanese society. He developed a distinctive visual style characterized by elaborate tracking shots and compositions that emphasized spatial relationships between characters and their environments. His international breakthrough came in the early 1950s when his films began winning major awards at European film festivals, particularly Venice. Despite his critical acclaim, Mizoguchi struggled with alcoholism and maintained a difficult personal life, which often informed his artistic vision. He completed his final film shortly before his death from leukemia in 1956, leaving behind a legacy of over 80 films that continue to influence filmmakers worldwide.

The Craft

Behind the Camera

Mizoguchi was renowned for his distinctive directing style characterized by long, flowing takes and elaborate tracking shots that created a sense of visual poetry and fluidity. He often used a one-scene-one-cut approach, maintaining visual continuity within scenes through carefully choreographed camera movements that followed characters through their environments. His compositions frequently emphasized the spatial relationships between characters and their surroundings, using depth of field to create layered visual narratives. Mizoguchi's visual style was complemented by his humanistic approach to storytelling, focusing particularly on the suffering and resilience of women in patriarchal Japanese society. He was known for his meticulous pre-planning and storyboarding, ensuring that every camera movement served the emotional and thematic content of his films.

Milestones

- Directed first film 'The Return of the Spirit' (1923)

- Created masterpiece 'Sisters of the Gion' (1936) establishing his signature style

- Directed 'The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum' (1939), considered his first mature work

- Won Venice Film Festival Silver Lion for 'Ugetsu' (1953)

- Won Venice Film Festival Silver Lion for 'Sansho the Bailiff' (1954)

- Completed over 80 films during his 33-year career

- Influenced generations of international filmmakers with his visual techniques

Best Known For

Must-See Films

Accolades

Won

- Venice Film Festival Silver Lion for Best Director (1952) - The Life of Oharu

- Venice Film Festival Silver Lion (1953) - Ugetsu

- Venice Film Festival Silver Lion (1954) - Sansho the Bailiff

- Kinema Junpo Award for Best Director (1952) - The Life of Oharu

- Mainichi Film Award for Best Director (1951) - Miss Oyu

- Mainichi Film Award for Best Director (1953) - Ugetsu

- Mainichi Film Award for Best Director (1954) - Sansho the Bailiff

Nominated

- Academy Award nomination for Best Costume Design (1954) - Ugetsu

- BAFTA nomination for Best Film (1955) - Ugetsu

- Cannes Film Festival Grand Prize (1952) - The Life of Oharu

Special Recognition

- Retrospective at Cannes Film Festival (1975)

- Retrospective at Museum of Modern Art, New York

- Japanese government Order of Culture (posthumous)

- Ranked among greatest directors in Sight & Sound polls

- Films preserved in Criterion Collection

Working Relationships

Worked Often With

Studios

Why They Matter

Impact on Culture

Mizoguchi revolutionized cinematic language with his innovative camera techniques and profoundly humanistic storytelling, establishing Japanese cinema as a major artistic force on the international stage. His films provided critical social commentary on post-war Japanese society, particularly addressing the plight of women in a patriarchal culture, making him a feminist voice in cinema long before such perspectives became common. His visual innovations, particularly his use of long takes and tracking shots, influenced generations of filmmakers globally, from Orson Welles to Andrei Tarkovsky. Mizoguchi's success at international film festivals in the 1950s helped open doors for other Japanese directors, including Akira Kurosawa and Yasujiro Ozu, to gain recognition abroad. His films continue to be studied in film schools worldwide as exemplars of visual storytelling and social consciousness in cinema.

Lasting Legacy

Kenji Mizoguchi's legacy endures as one of cinema's great auteurs, a master filmmaker whose technical innovations and humanistic vision continue to resonate with contemporary audiences and filmmakers. His visual style, particularly his flowing camera movements and long takes, has become part of the cinematic language that directors continue to study and emulate. Mizoguchi's focus on social injustice and the female perspective established him as a pioneering voice for social consciousness in cinema, influencing filmmakers who use their art as a vehicle for social commentary. His films remain in active distribution through the Criterion Collection and other specialty distributors, ensuring that new generations of film enthusiasts can discover his work. Film scholars continue to analyze his techniques and themes, and he consistently ranks among the greatest directors in international critics' polls, cementing his place in the pantheon of cinema masters.

Who They Inspired

Mizoguchi's influence extends across generations of international filmmakers who have adopted his visual techniques and thematic concerns. His fluid camera work and long takes directly influenced directors like Andrei Tarkovsky, Satyajit Ray, and Theo Angelopoulos, who similarly used extended takes to create meditative, poetic cinema. Contemporary directors such as Hou Hsiao-hsien, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, and Kelly Reichardt have cited Mizoguchi as a major influence on their patient, observational approach to filmmaking. His focus on women's stories and social injustice paved the way for feminist filmmakers and socially conscious directors worldwide. Even commercial filmmakers have borrowed elements of his visual style, particularly his tracking shots and compositional techniques. Film schools worldwide continue to study his work as exemplary of how technical mastery can serve emotional and thematic storytelling, ensuring his influence persists through new generations of filmmakers.

Off Screen

Mizoguchi's personal life was marked by hardship and turbulence, deeply influencing his artistic vision. Born into a struggling family, his father's failed business and his sister's sale into geishadom left lasting scars that informed his films' themes of female suffering. He was married twice, first to actress Chieko Mihara and later to actress Kinuyo Tanaka, though both marriages ended in divorce. His relationship with Tanaka was particularly tumultuous, marked by professional collaboration and personal conflict. Mizoguchi struggled with alcoholism throughout his life, which affected his health and relationships. Despite his professional success, he remained a deeply private and often difficult individual, channeling his personal demons into his artistic work.

Education

Attended primary school in Tokyo, left formal education early due to family poverty. Studied Western painting at Aohashi Western Painting Research Institute before entering film industry. Largely self-taught in filmmaking through practical experience rather than formal education.

Family

- Chieko Mihara (1927-1932)

- Kinuyo Tanaka (1940-1954)

Did You Know?

- His sister was sold into geishadom as a child, an experience that haunted him throughout his life and influenced his films about women's suffering

- He directed over 80 films but only about 30 survive today due to war and neglect

- Mizoguchi was known for his extreme perfectionism, sometimes requiring hundreds of takes for a single scene

- He was one of the three great masters of Japanese cinema along with Yasujiro Ozu and Akira Kurosawa

- His film 'Ugetsu' was one of the first Japanese films to gain widespread international acclaim

- He often worked with the same cinematographer, Kazuo Miyagawa, who helped create his signature visual style

- Despite his success, he remained relatively unknown in Japan during his lifetime compared to his international reputation

- His final film 'Street of Shame' was banned in Japan for its depiction of prostitution

- He was known for his difficult personality and often clashed with actors and crew

- His films typically featured strong female protagonists, unusual for male directors of his era

In Their Own Words

The difficulty of making films is enormous. The difficulty of making a great film is even greater.

I want to portray the necessity of human beings living together, the necessity of love and mutual understanding.

A film should be like a window through which we can see the world.

The cinema is a mirror by which we see ourselves.

I have always been interested in the fate of women, in their suffering and their struggle for freedom.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who was Kenji Mizoguchi?

Kenji Mizoguchi was one of Japan's most acclaimed film directors, known for his masterful visual style and films focusing on women's suffering and social injustice. He was active from the 1920s until his death in 1956, creating over 80 films and gaining international recognition for works like 'Ugetsu' and 'Sansho the Bailiff'.

What films is Kenji Mizoguchi best known for?

Mizoguchi is best known for his masterpieces 'Ugetsu' (1953), 'Sansho the Bailiff' (1954), 'The Life of Oharu' (1952), and his earlier works 'Sisters of the Gion' (1936) and 'Osaka Elegy' (1936). These films showcase his signature style and thematic concerns about women's suffering and social injustice.

When was Kenji Mizoguchi born and when did he die?

Kenji Mizoguchi was born on May 16, 1898, in Tokyo, Japan, and died on August 24, 1956, at the age of 58 from leukemia. His career spanned from 1923 to 1956, covering both the silent and sound eras of Japanese cinema.

What awards did Kenji Mizoguchi win?

Mizoguchi won three Venice Film Festival Silver Lions for 'The Life of Oharu' (1952), 'Ugetsu' (1953), and 'Sansho the Bailiff' (1954). He also received multiple Mainichi Film Awards for Best Director and was posthumously honored with the Japanese government's Order of Culture.

What was Kenji Mizoguchi's directing style?

Mizoguchi's directing style was characterized by long, flowing takes, elaborate tracking shots, and meticulous compositions that emphasized spatial relationships. He often used a one-scene-one-cut approach and focused on the suffering and resilience of women in Japanese society, creating films that combined visual poetry with social commentary.

Learn More

Films

4 films