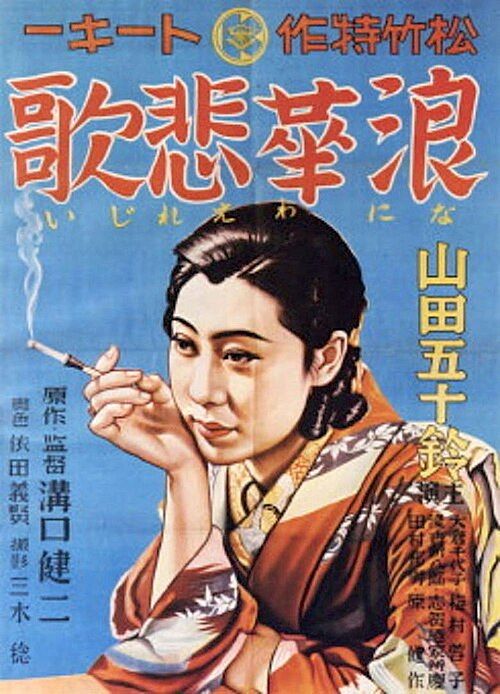

Osaka Elegy

Plot

Ayako Murai, a young telephone operator in Osaka, becomes the mistress of her boss, Mr. Asai, to pay off her father's embezzlement debt and prevent him from going to prison. As she sacrifices her reputation and relationship with her boyfriend Nishimura, Ayako must also support her family financially, including paying for her sister's expensive marriage arrangements. The situation becomes increasingly complicated when Mr. Asai's possessive wife discovers the affair and confronts Ayako, leading to her complete social ostracization. In the film's devastating conclusion, Ayako walks through the streets of Osaka, utterly alone and abandoned by everyone she tried to help, having sacrificed everything for her family's well-being. The film serves as a powerful critique of patriarchal society and the impossible choices faced by women in pre-war Japan.

About the Production

The film was produced during a particularly creative period for Mizoguchi, who made three films in 1936. It was shot quickly on a modest budget but features Mizoguchi's signature long takes and tracking shots. The production faced some censorship challenges due to its critical portrayal of Japanese society and its frank depiction of a woman's sexual agency. The film's urban setting was unusual for Japanese cinema of the period, which often focused on rural or traditional settings.

Historical Background

Osaka Elegy was produced during a period of significant social and political transformation in Japan. The mid-1930s saw increasing militarization and nationalism, with the government exercising growing control over cultural production. The film emerged during Japan's rapid industrialization and urbanization, with cities like Osaka becoming centers of modern capitalism and changing social mores. This period also saw the emergence of the 'modern girl' (moga) in Japanese society - young women who adopted Western fashions and attitudes. The film's critique of traditional family structures and its sympathetic portrayal of a woman making difficult moral choices was particularly bold given the conservative, patriarchal values being promoted by the increasingly militaristic government. The Great Depression's effects were still being felt in Japan, creating economic pressures that led to the kinds of family financial crises depicted in the film.

Why This Film Matters

Osaka Elegy is considered a landmark film in Japanese cinema for its bold social criticism and innovative visual style. It established many of the themes that would define Kenji Mizoguchi's career: the oppression of women in patriarchal society, the conflict between traditional values and modern life, and the sacrifice of individual happiness for family duty. The film's realistic depiction of urban working-class life was groundbreaking for Japanese cinema, which had often focused on samurai stories or rural dramas. Its influence can be seen in the work of later Japanese directors like Yasujirō Ozu and Nagisa Ōshima, who also explored themes of family pressure and social conformity. The film is now recognized as a masterpiece of early Japanese sound cinema and helped establish Mizoguchi as one of the world's great directors. Its preservation and restoration have allowed modern audiences to appreciate its artistic achievements and social commentary.

Making Of

Mizoguchi was known for his demanding directing style, often requiring dozens of takes for perfect emotional timing. For Osaka Elegy, he worked closely with cinematographer Minoru Miki to develop the film's distinctive visual style, featuring long, flowing camera movements that follow characters through urban spaces. The production team spent considerable time researching authentic Osaka locations and working-class life to ensure the film's realism. Isuzu Yamada underwent extensive preparation for her role, studying the mannerisms and speech patterns of Osaka women. The film's controversial themes required careful navigation of the increasingly strict censorship system in 1930s Japan, with Mizoguchi having to make subtle adjustments to appease censors while maintaining his critical perspective.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Minoru Miki is notable for its innovative use of long takes and fluid camera movements that follow characters through urban spaces. Mizoguchi and Miki developed a distinctive visual style that emphasizes the constraints placed on characters, often framing them through doorways, windows, or other architectural elements that suggest their entrapment. The film uses deep focus and careful composition to create rich, layered images that convey social relationships and power dynamics. The urban setting is captured with remarkable realism, with scenes filmed on location in Osaka's streets and buildings. The visual style contrasts the freedom of camera movement with the constriction of the characters' lives, creating a powerful visual metaphor for the film's themes. The lighting, particularly in interior scenes, creates a sense of claustrophobia and emotional intensity that enhances the dramatic impact.

Innovations

Osaka Elegy was technically innovative for its time, particularly in its use of sound and camera movement. The film features some of the earliest examples of complex tracking shots in Japanese cinema, with the camera following characters through multiple spaces in single takes. The sound recording was challenging given the film's location shooting in urban Osaka, requiring innovative techniques to capture clear dialogue while maintaining ambient environmental sounds. The film's editing style, with its relatively long takes and smooth transitions between scenes, was ahead of its time and influenced later developments in cinematic language. The preservation and restoration of the film have been technical achievements in themselves, allowing modern audiences to experience the film with improved image and sound quality while maintaining its original artistic integrity.

Music

The film features a musical score by Senji Takahashi that blends traditional Japanese musical elements with Western-style orchestration typical of 1930s cinema. The soundtrack uses music to emphasize emotional moments and create atmosphere, particularly in scenes highlighting Ayako's isolation and sacrifice. The sound design was innovative for its time, using diegetic sounds of Osaka - street noises, telephone rings, factory sounds - to create a realistic urban environment. The film was made during the transition from silent to sound cinema in Japan, and Mizoguchi uses sound to enhance rather than dominate the visual storytelling. The musical themes recur throughout the film, creating emotional continuity and underscoring the tragic nature of Ayako's situation.

Famous Quotes

"A woman's life is one of sacrifice. We must be prepared to give everything for those we love." - Ayako Murai

"In this world, money is everything. Without it, even family ties mean nothing." - Mr. Asai

"I did what I had to do. Can anyone truly say they would have done differently?" - Ayako Murai

"The city takes everything and gives nothing in return. We are all just ghosts in these streets." - Ayako Murai

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence following Ayako through the busy Osaka telephone exchange, establishing her as a modern working woman in urban Japan.

- The tense confrontation scene between Ayako and Mr. Asai's wife, where the social and sexual power dynamics are laid bare.

- The heartbreaking scene where Ayako gives her hard-earned money to her ungrateful family, who accept it without acknowledging her sacrifice.

- The final tracking shot following Ayako through the empty streets of Osaka at night, completely alone and abandoned, embodying the film's themes of urban alienation and social ostracism.

- The scene where Ayako meets her former boyfriend Nishimura, highlighting the social cost of her choices and the impossibility of returning to her previous life.

Did You Know?

- The film was banned in Japan by wartime censors for its 'depressing' and 'unpatriotic' content, as it criticized traditional family structures and social hypocrisy.

- Isuzu Yamada, who plays Ayako, was only 19 years old when she filmed this role, yet delivered what many consider one of the most powerful performances in Japanese cinema history.

- Director Kenji Mizoguchi claimed this was his first truly successful film in terms of achieving his artistic vision.

- The film's original Japanese title 'Naniwa Erejī' uses 'Naniwa,' the old name for Osaka, emphasizing the film's urban setting.

- Mizoguchi was inspired by real newspaper stories about women who sacrificed themselves for their families.

- The film was considered lost for many years before a print was discovered and preserved.

- It was one of the first Japanese films to explicitly critique capitalism and its effects on family life.

- The film's ending was considered so controversial that it was sometimes cut for screenings in more conservative areas.

- Mizoguchi and Yamada would collaborate on several more films, including 'Ugetsu' and 'The Life of Oharu.'

- The film's realistic depiction of Osaka life was praised for its authenticity and attention to detail.

What Critics Said

Contemporary Japanese critics praised the film's realism and social relevance, with Kinema Junpo naming it the best film of 1936. However, some conservative critics found its themes too depressing and unpatriotic. International recognition came much later, after World War II, when film critics in the West discovered Mizoguchi's work. Today, Osaka Elegy is universally acclaimed as a masterpiece, with particular praise for Isuzu Yamada's performance, Mizoguchi's direction, and the film's bold social critique. Critics have noted how the film's visual style - particularly its long takes and tracking shots - perfectly serves its thematic concerns. The film is frequently cited in surveys of the greatest films ever made, and it's considered essential viewing for understanding the development of Japanese cinema and Mizoguchi's artistic vision.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reception in Japan was mixed, with some viewers finding the film too depressing or critical of Japanese society. The film's urban setting and working-class characters resonated with many viewers who recognized similar struggles in their own lives. However, the film's censorship and limited distribution meant that many Japanese audiences never had the opportunity to see it during its initial release. In the decades following World War II, as the film was rediscovered and restored, it gained a strong following among film enthusiasts and art house audiences. Modern audiences, particularly those interested in classic cinema and social commentary, have embraced the film as a powerful work that remains relevant in its critique of gender inequality and family pressure.

Awards & Recognition

- Kinema Junpo Award for Best Film of 1936

Film Connections

Influenced By

- German Expressionist cinema

- French poetic realism

- Japanese literary naturalism

- Social realist theater

- Contemporary newspaper stories

This Film Influenced

- The Life of Oharu (1952)

- Ugetsu (1953)

- Tokyo Story (1953)

- Late Spring (1949)

- The Inheritance (1962)

- The Family Game (1983)

- Tokyo Sonata (2008)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was considered partially lost for decades but has been fully restored. A complete 35mm print was discovered and preserved by the National Film Center of Japan. The Criterion Collection released a digitally restored version on Blu-ray in 2020 as part of their Kenji Mizoguchi collection. The restoration work involved combining elements from multiple prints to create the most complete version possible. The film is now preserved in several archives worldwide, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the British Film Institute.