The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum

Plot

In late 19th century Tokyo, Kikunosuke Onoue is the adopted son of a legendary Kabuki actor, but despite his family's prestigious position, he struggles with his craft as an actor specializing in female roles (onnagata). When Kikunosuke discovers that his family and colleagues have been falsely praising his mediocre performances out of deference to his father's legacy, he becomes devastated and emotionally isolated. Finding genuine solace only with Otoku, his family's devoted servant, the two fall deeply in love despite the strict social hierarchies that forbid such relationships. Determined to prove his worth as an actor on his own merits, Kikunosuke leaves his comfortable home and family behind, with Otoku choosing to sacrifice her own position to follow him into poverty and uncertainty. Years of struggle follow as Kikunosuke hones his craft in provincial theaters while Otoku supports him through illness and hardship, their bond deepening through shared sacrifice. In the end, Kikunosuke achieves artistic mastery and recognition, but only after Otoku's tragic death, leaving him to perform his greatest role alone, forever marked by the woman who believed in him when no one else would.

About the Production

The film was made during Japan's increasing militarization and censorship, yet Mizoguchi managed to create a deeply personal work that subtly critiqued traditional social structures. The production faced challenges due to the growing film industry consolidation in Japan, with Shinkō Kinema being absorbed into larger conglomerates during filming. The elaborate Kabuki sequences required extensive research and consultation with theater experts to ensure authenticity in both costume and performance techniques. The film's long takes and complex camera movements were technically ambitious for the time, requiring specially modified camera equipment to achieve Mizoguchi's signature flowing style.

Historical Background

The film was produced in 1939, a pivotal year in world history as tensions were escalating toward global conflict. Japan was deep into its period of militarization and expansionism, having already invaded Manchuria in 1931 and launched a full-scale war against China in 1937. The Japanese government was implementing increasingly strict censorship controls over all cultural production, including cinema, requiring films to support nationalistic themes and avoid criticism of traditional Japanese values. Despite these constraints, Mizoguchi managed to create a work that, while appearing to celebrate traditional Japanese culture, actually contains subtle critiques of social hierarchies and the treatment of women. The film's setting in the Meiji era (late 19th century) was significant, as this period represented Japan's rapid modernization and Westernization, creating tensions between traditional and modern values that resonated with contemporary audiences. The Kabuki theater world depicted in the film was itself undergoing changes during this period, as traditional arts struggled to maintain relevance in an increasingly industrialized and militarized society. The film's emphasis on artistic integrity and personal sacrifice took on particular meaning in a time when individual expression was increasingly subordinated to collective national goals.

Why This Film Matters

'The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum' represents a pinnacle of Japanese cinema's golden age and is considered one of Mizoguchi's most accomplished works. The film's influence extends far beyond its immediate impact, establishing techniques and approaches that would influence generations of filmmakers worldwide. Its visual style, characterized by long takes, deep focus, and fluid camera movements, demonstrated how cinema could achieve the complexity and emotional depth of traditional Japanese arts like Kabuki and Noh theater. The film's exploration of gender roles, particularly through the onnagata tradition of male actors playing female roles, offered subtle commentary on performance, identity, and social construction that would resonate with later feminist film theory. Its depiction of the relationship between artistic achievement and personal sacrifice became a template for countless films about creative struggle. The film's rediscovery in the 1970s played a crucial role in the international reassessment of Japanese cinema, helping to establish Mizoguchi alongside Kurosawa and Ozu as one of Japan's three great masters. Its restoration and preservation have been instrumental in maintaining awareness of pre-war Japanese cinema, a period when many films were lost due to war, neglect, and the unstable nature of early film stock. The film continues to be studied in film schools worldwide as an example of how formal innovation can serve emotional storytelling rather than mere technical display.

Making Of

The production of 'The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum' represented a turning point in Kenji Mizoguchi's career, marking his emergence as a master of cinematic form. Mizoguchi, known for his perfectionism and demanding nature on set, pushed his actors to emotional and physical extremes, particularly in the scenes depicting poverty and illness. The relationship between Mizoguchi and lead actor Shōtarō Hanayagi was initially tense, as the Kabuki performer was unaccustomed to film acting techniques, but eventually developed into mutual respect. The film's elaborate Kabuki sequences required months of preparation, with Mizoguchi insisting on authentic costumes, makeup, and performance styles down to the smallest details. Cinematographer Minoru Miki worked closely with Mizoguchi to develop the fluid camera movements that would become the director's trademark, often using complex tracking shots that followed characters through multiple rooms and outdoor spaces. The production team faced significant challenges recreating 19th-century Tokyo, as many traditional buildings had been destroyed in the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake. Despite wartime resource constraints, Mizoguchi secured funding for historically accurate sets and costumes, believing that authenticity was essential to the film's emotional impact. The film's extended production schedule and budget overruns caused tension with studio executives, but Mizoguchi's growing reputation allowed him to maintain creative control.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum' represents a milestone in visual storytelling, showcasing Mizoguchi's signature style of long, flowing takes and carefully composed deep focus shots. Cinematographer Minoru Miki employed revolutionary tracking techniques that followed characters through multiple spaces without cutting, creating a sense of continuous time and space that immerses viewers in the narrative world. The film's visual language draws heavily from traditional Japanese arts, particularly the composition principles of ukiyo-e woodblock prints and the spatial awareness of Noh theater staging. The camera often maintains a respectful distance from the actors, observing their actions from a slightly elevated angle that suggests both objectivity and a sense of fatalism. The lighting design masterfully contrasts the artificial, theatrical illumination of the Kabuki stage with the natural, often harsh lighting of the characters' real lives, visually reinforcing the film's themes of performance versus authenticity. The film's use of mirrors and reflective surfaces creates complex visual relationships between characters and their environments, suggesting the fragmented nature of identity and social role. The color palette, though limited by the black-and-white technology of the era, achieves remarkable tonal richness, particularly in the rendering of traditional costumes and architectural details. The cinematography's most innovative aspect may be its treatment of time, with long takes that stretch moments of emotional intensity to their breaking point, forcing viewers to experience the characters' suffering and triumph in real-time.

Innovations

The film represents several technical innovations that were groundbreaking for Japanese cinema in 1939. The most significant achievement was the development of a complex camera crane system that allowed for the smooth, extended tracking shots that became Mizoguchi's trademark. The production team created special dollies and tracks that could navigate the narrow confines of traditional Japanese architecture, enabling the camera to follow characters through multiple rooms without interruption. The film's lighting setup was particularly innovative, combining traditional Japanese paper lanterns with modern electrical equipment to achieve the distinctive visual contrast between theatrical and domestic spaces. The sound recording equipment was modified to better capture the nuances of Kabuki performance, which required balancing amplified stage dialogue with intimate off-stage conversations. The makeup and costume departments achieved remarkable authenticity in recreating 19th-century Kabuki styles, developing new techniques for the onnagata makeup that would withstand the scrutiny of close-up photography. The film's editing, while maintaining Mizoguchi's preference for long takes, employed subtle rhythmic patterns that created emotional momentum without relying on conventional cutting techniques. The production also pioneered methods for filming theatrical performance that avoided disrupting the actual performances, using multiple cameras and carefully planned angles to capture both the spectacle and the intimate details of the actors' expressions.

Music

The film's soundtrack was composed by Shirō Fukai, who created a score that masterfully blended traditional Japanese musical elements with Western orchestral techniques. The music prominently features the shamisen and other traditional Japanese instruments during the Kabuki sequences, creating an authentic atmosphere of the theatrical world depicted in the film. Fukai's score employs leitmotifs for the main characters, with Otoku's theme particularly notable for its gentle, melancholic quality that evolves throughout the film to reflect her changing circumstances. The sound design carefully distinguishes between the amplified, theatrical sounds of the Kabuki performances and the more naturalistic audio of the characters' private moments, creating a sonic contrast that reinforces the film's thematic concerns. The film makes innovative use of silence, particularly in scenes of emotional crisis, where the absence of music amplifies the tension and allows the performances to carry the full emotional weight. The recording techniques of 1939 presented significant challenges, particularly in capturing the dynamic range of both dialogue and musical performances, yet the film achieves remarkable clarity and balance. The soundtrack also incorporates diegetic music from the Kabuki performances themselves, blurring the line between narrative and musical elements in ways that anticipate later experiments in cinematic sound. The overall musical approach emphasizes the cyclical nature of the story, with recurring themes that undergo subtle variations as the characters' relationships evolve.

Famous Quotes

If you truly love me, you must let me fail on my own terms.

Praise without truth is a poison that kills the soul.

In the theater, we wear masks to show our truest selves.

A flower that blooms in winter is more precious than one that blooms in spring.

The greatest performance is not on stage but in the silence between scenes.

To be an artist is to choose loneliness over comfort.

Your belief in me is the only stage I need.

In this world, some loves are written in water, others in stone.

The curtain falls, but the story continues in the heart.

Even the last chrysanthemum has its moment of perfect bloom.

Memorable Scenes

- The devastating scene where Kikunosuke overhears his family's honest criticism of his acting, shattering his self-delusion and forcing him to confront his mediocrity.

- The extended tracking shot following Otoku as she leaves her comfortable position to join Kikunosuke in poverty, her determination visible in every step.

- The climactic Kabuki performance where Kikunosuke finally achieves artistic mastery, intercut with Otoku's declining health, creating a powerful juxtaposition of artistic triumph and personal tragedy.

- The intimate scene where Kikunosuke and Otoku share a simple meal in their impoverished dwelling, their love transcending the harshness of their circumstances.

- The final scene where Kikunosuke performs alone on stage, the empty space beside him a ghostly reminder of Otoku's absence, his art now perfected but his heart broken.

Did You Know?

- The film was considered lost for decades until a print was discovered in the 1970s in the Daiei Film studio collection, allowing for its international rediscovery.

- Director Kenji Mizoguchi considered this his favorite among all his films, viewing it as the most complete expression of his artistic vision.

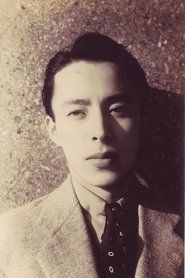

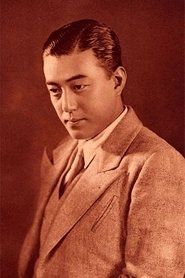

- The lead actor Shōtarō Hanayagi was actually a real Kabuki actor from a prestigious theatrical family, bringing authentic experience to the role.

- The film's title refers to the last chrysanthemum of autumn, symbolizing both beauty in decline and the fleeting nature of artistic achievement.

- Mizoguchi's famous long take style was influenced by his background in silent cinema, where he had to convey emotion through visual means rather than dialogue.

- The film was made during the period when Japanese authorities were increasingly censoring films, yet it escaped major cuts due to its seemingly traditional subject matter.

- Otoku's character was based on a real person from the Kabuki world, though historical details have been fictionalized for dramatic purposes.

- The film's production coincided with the outbreak of World War II in Europe, though Japan wouldn't enter the war until 1941.

- Mizoguchi's sister, who had supported him through poverty and illness, was a major inspiration for the character of Otoku.

- The Kabuki performances in the film were not staged for the camera but were actual performances filmed during breaks in the narrative sequences.

What Critics Said

Upon its initial release in 1939, the film received critical acclaim in Japan, with critics praising its technical mastery and emotional depth. The Kinema Junpo, Japan's most prestigious film publication, named it the best film of the year, recognizing Mizoguchi's achievement in blending traditional Japanese aesthetics with modern cinematic techniques. Contemporary Japanese reviewers particularly noted the authenticity of the Kabuki sequences and the powerful performances of the lead actors. However, the film's international recognition was limited by the outbreak of World War II, which severely restricted the distribution of Japanese films abroad. It wasn't until the 1950s, following Mizoguchi's international breakthrough with films like 'Ugetsu' and 'The Life of Oharu,' that Western critics began to seek out his earlier works. When the film was rediscovered and screened internationally in the 1970s, critics hailed it as a lost masterpiece, with many considering it superior to some of Mizoguchi's more famous later works. The film's reputation has continued to grow, with modern critics praising its sophisticated visual style, complex narrative structure, and profound emotional impact. The Criterion Collection's release of the film in 2008 brought it to a new generation of viewers, with critics noting its influence on filmmakers ranging from Andrei Tarkovsky to Hou Hsiao-hsien. Today, it is widely regarded as one of the greatest films ever made, regularly appearing on critics' polls of the best films of all time.

What Audiences Thought

Contemporary Japanese audiences in 1939 responded positively to the film, particularly appreciating its authentic depiction of the Kabuki world and its exploration of traditional Japanese values. The film's themes of artistic dedication and personal sacrifice resonated strongly with viewers during a period of national crisis and uncertainty. The romance between Kikunosuke and Otoku, while controversial due to the class differences, was seen as emotionally authentic and moving by many viewers. However, the film's lengthy runtime and deliberate pacing may have limited its commercial appeal compared to more conventional entertainments of the period. The film's box office performance was respectable but not spectacular, as was common for prestige productions during this era. In post-war years, the film was largely unseen by Japanese audiences due to the loss of prints and the focus on newer productions. Following its rediscovery and restoration, the film has found appreciative audiences among cinema enthusiasts and art house viewers worldwide. Modern audiences often comment on the film's timeless themes and its visually stunning presentation, though some find its slow pace challenging by contemporary standards. The film's reputation has grown significantly through home video releases and screenings at film festivals and cinematheques, where it continues to move audiences with its powerful emotional content and technical mastery.

Awards & Recognition

- Kinema Junpo Award for Best Film of the Year (1939)

- Mainichi Film Concours for Best Film (1939)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Traditional Kabuki and Noh theater aesthetics

- Ukiyo-e woodblock print compositions

- The novels of Jun'ichirō Tanizaki

- The plays of Kaoru Osanai

- German Expressionist cinema

- Soviet montage theory (particularly in its rejection of rapid cutting)

- Traditional Japanese scroll painting narrative techniques

- The writings of Natsume Sōseki on modern Japanese identity

This Film Influenced

- Ugetsu (1953) - also directed by Mizoguchi

- The Life of Oharu (1952) - Mizoguchi's exploration of female sacrifice

- Rashomon (1950) - influenced by its theatrical presentation of truth

- In the Mood for Love (2000) - influenced by its visual treatment of constrained romance

- The Last Emperor (1987) - influenced by its depiction of traditional arts in modern times

- Farewell My Concubine (1993) - similar exploration of theater and personal identity

- Eternity and a Day (1998) - influenced by its long take style and temporal themes

- In the Realm of the Senses (1976) - influenced by its treatment of obsessive love and social constraints

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was believed lost for decades until a complete 35mm print was discovered in the Daiei studio collection in the 1970s. The discovered print was in remarkably good condition, though it showed some signs of deterioration typical of films from this era. The film underwent a major restoration in the early 2000s as part of a project to preserve and restore classic Japanese cinema, with funding from international film preservation organizations. The restored version premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 2005 and was subsequently released on DVD by The Criterion Collection in 2008. The restoration process involved digital cleaning of the original elements, careful color grading to preserve the black-and-white tonal qualities, and the creation of new preservation negatives. The film is now preserved in several archives worldwide, including the National Film Center of Japan, the Cinémathèque Française, and the Museum of Modern Art's film department. The original negative is stored under climate-controlled conditions at the National Film Archive of Japan, ensuring its long-term preservation for future generations.