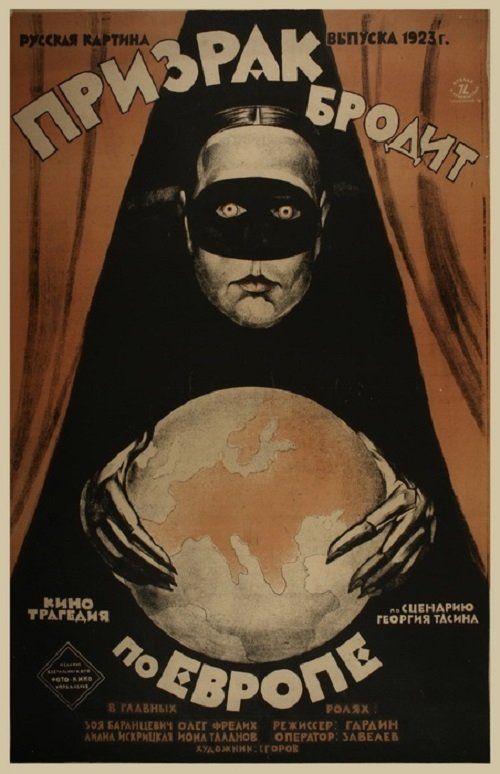

A Spectre Haunts Europe

Plot

Set in an imaginary European kingdom during a time of revolutionary upheaval, the Emperor, fearing the growing specter of revolution, decides to seek refuge in one of the most remote regions of his empire. In this isolated outpost, he encounters Elka, the daughter of a revolutionary who has been exiled to this distant land for his subversive activities. Despite their opposing backgrounds and the political tensions dividing them, the Emperor and Elka fall deeply in love, forming a forbidden romance that transcends class and political boundaries. Their relationship, however, is doomed from the start as the revolutionary forces, led by Elka's own father, advance upon the palace with destructive intent. The film culminates in tragedy as the revolutionaries storm the palace, destroying both the physical structure and the lovers' dreams, leaving both the Emperor and Elka dead in the violent overthrow of the old order.

About the Production

This film was produced during the early years of Soviet cinema when the industry was still establishing itself after the Bolshevik Revolution. The title directly references Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels' 'The Communist Manifesto,' which begins 'A spectre is haunting Europe—the spectre of communism.' The film was part of the early Soviet effort to create politically engaged cinema that supported the revolutionary ideals of the new state while still maintaining dramatic and artistic qualities that could appeal to mass audiences.

Historical Background

The film was produced in 1923, a pivotal year in early Soviet history. The Russian Revolution had occurred six years earlier, and the country was still recovering from the devastating Russian Civil War (1918-1922). The New Economic Policy (NEP) had been introduced in 1921, allowing limited private enterprise and cultural experimentation. This period saw the Soviet government beginning to systematically organize the film industry for propaganda purposes, with the establishment of Goskino in 1922. The film's themes of revolution and the overthrow of monarchy directly reflected the recent historical experience of the Russian people, while its imaginary setting allowed for a more universal exploration of revolutionary themes. The early 1920s also saw Soviet filmmakers developing their own cinematic language, distinct from both pre-revolutionary Russian cinema and contemporary European film movements.

Why This Film Matters

'A Spectre Haunts Europe' represents an important transitional work in the development of Soviet cinema, bridging the gap between pre-revolutionary melodramatic traditions and the more formally experimental and politically explicit films that would emerge later in the 1920s with directors like Sergei Eisenstein and Vsevolod Pudovkin. The film demonstrates how early Soviet filmmakers attempted to reconcile popular entertainment forms with revolutionary ideology, using familiar romantic melodrama conventions to explore political themes. Its title's direct reference to Marxist theory shows how thoroughly political discourse had penetrated Soviet cultural production. The film also illustrates the early Soviet approach to class conflict themes, portraying the tragic romance between a revolutionary's daughter and an emperor as symbolic of the impossible reconciliation between old and new orders. While less formally innovative than later Soviet masterpieces, it contributed to establishing the pattern of politically engaged cinema that would become a hallmark of Soviet film culture.

Making Of

The production of 'A Spectre Haunts Europe' took place during a formative period for Soviet cinema, when the new Bolshevik government was still figuring out how to use film as a tool for political education and propaganda. Director Vladimir Gardin, who had been an established figure in pre-revolutionary Russian cinema, had to adapt his filmmaking style to serve the new ideological requirements of the Soviet state. The film was shot on location in Moscow using the limited technical resources available in the early 1920s, when Soviet cinema was still recovering from the disruptions of the revolution and civil war. The casting of Oleg Frelikh as the Emperor was significant, as he was one of the leading romantic actors of the era, capable of bringing both dignity and vulnerability to the role of a doomed monarch. The production faced numerous challenges, including shortages of film stock, limited studio facilities, and the need to create elaborate period costumes and sets despite severe economic constraints in the early Soviet period.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'A Spectre Haunts Europe' would have reflected the technical limitations and aesthetic conventions of early Soviet cinema in 1923. The film was likely shot using available equipment from the pre-revolutionary period, with relatively static camera positions typical of early 1920s filmmaking. The visual style would have emphasized the contrast between the opulent palace settings and the more modest surroundings of the revolutionary characters, using lighting and composition to reinforce the film's class conflict themes. The cinematographer would have employed dramatic lighting to enhance the romantic and tragic elements of the story, while also creating visual distinctions between the old aristocratic world and the emerging revolutionary order. The film's visual approach would have been less experimental than the montage techniques that would later become associated with Soviet cinema, but still effective in conveying the emotional and political dimensions of the narrative.

Innovations

While 'A Spectre Haunts Europe' does not appear to have introduced major technical innovations, it represents the technical capabilities of early Soviet cinema in 1923. The film would have been shot on nitrate film stock using cameras and equipment from the pre-revolutionary period, as the Soviet film industry was still developing its technical infrastructure. The production likely involved creating elaborate sets and costumes to depict the imaginary kingdom and its palace, demonstrating the resourcefulness of Soviet filmmakers working with limited means. The film's existence itself is a technical achievement considering the economic difficulties and material shortages faced by the Soviet film industry during this early post-revolutionary period. The preservation of any footage from this era is particularly notable given the fragility of nitrate film and the political upheavals that affected film archives throughout Soviet history.

Music

As a silent film, 'A Spectre Haunts Europe' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical practice in Soviet cinemas of the 1920s involved either a pianist or small orchestra providing musical accompaniment that enhanced the emotional impact of the visual narrative. The score would have likely included popular classical pieces adapted to fit the film's romantic and dramatic moments, along with possibly revolutionary songs or musical themes that reinforced the film's political content. The choice of music would have been crucial in establishing the film's tone and guiding audience emotional responses, particularly during the romantic scenes between the Emperor and Elka and the tragic climax of the revolutionaries' assault on the palace.

Famous Quotes

Even in the furthest corners of the empire, the spectre of revolution follows us.

Love knows no class, but society does not forgive those who forget their place.

The old world must burn for the new to be born.

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic sequence where revolutionary forces storm the palace, intercutting the destruction of the aristocratic world with the tragic deaths of the Emperor and Elka, symbolizing both personal and political transformation.

Did You Know?

- The title 'A Spectre Haunts Europe' is a direct reference to the opening line of 'The Communist Manifesto' by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, published in 1848.

- Director Vladimir Gardin was one of the pioneers of Russian cinema, having begun his career before the 1917 Revolution and successfully transitioned to Soviet filmmaking.

- This film was produced by Goskino, the Soviet state film organization established in 1922 to centralize and control film production in the new Soviet state.

- The film represents an early example of Soviet cinema's attempt to combine revolutionary themes with traditional romantic drama.

- Many films from this early Soviet period have been lost due to the fragility of nitrate film stock and the political upheavals of the 20th century.

- The imaginary setting allowed the filmmakers to explore revolutionary themes without directly referencing contemporary Soviet politics, which could be sensitive.

- 1923 was a crucial year for Soviet cinema, marking the beginning of the state's systematic organization of film production and distribution.

- The film's tragic ending, with both lovers dying, was typical of melodramas of the era but also served to symbolize the death of the old aristocratic order.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of 'A Spectre Haunts Europe' is difficult to document due to the scarcity of surviving film criticism from this early Soviet period. However, based on the film's themes and production context, it likely received attention from Soviet cultural critics who were actively debating the role of cinema in the new socialist society. The film's combination of revolutionary themes with traditional melodramatic elements would have been seen as a safe approach to politically engaged filmmaking during the relatively experimental NEP period. Modern film historians have noted the film as an example of early Soviet cinema's attempts to create politically relevant content while maintaining popular appeal, though it is generally considered less significant than the more formally innovative works that would follow later in the decade.

What Audiences Thought

Information about specific audience reception for 'A Spectre Haunts Europe' is limited, but it can be inferred that the film appealed to Soviet audiences of the early 1920s who were still accustomed to pre-revolutionary melodramatic forms. The combination of romantic tragedy with revolutionary themes would have resonated with viewers who had experienced the recent upheavals of the revolution and civil war. The film's use of familiar genre conventions likely made its political messages more accessible to mass audiences who were still adapting to the new cultural landscape of Soviet Russia. During the NEP period, audiences had more diverse entertainment options, and films like this that balanced entertainment with ideological content were generally well-received.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Pre-revolutionary Russian melodrama

- Marxist political theory

- European romantic cinema

- Soviet propaganda aesthetics

This Film Influenced

- Later Soviet revolutionary melodramas

- Soviet films exploring class romance themes

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of 'A Spectre Haunts Europe' is uncertain, as is common with many early Soviet films from this period. Many films from 1923 have been lost due to the deterioration of nitrate film stock and the various political upheavals that affected Soviet film archives throughout the 20th century. If any footage survives, it would likely be held in the Gosfilmofond archive in Moscow, the main repository of Russian and Soviet cinema. The film's obscurity suggests that it may be partially or completely lost, which would be typical for a non-landmark Soviet film from this early period. However, ongoing restoration efforts by film archives occasionally rediscover films thought to be lost, so the complete preservation status may not be definitively known.