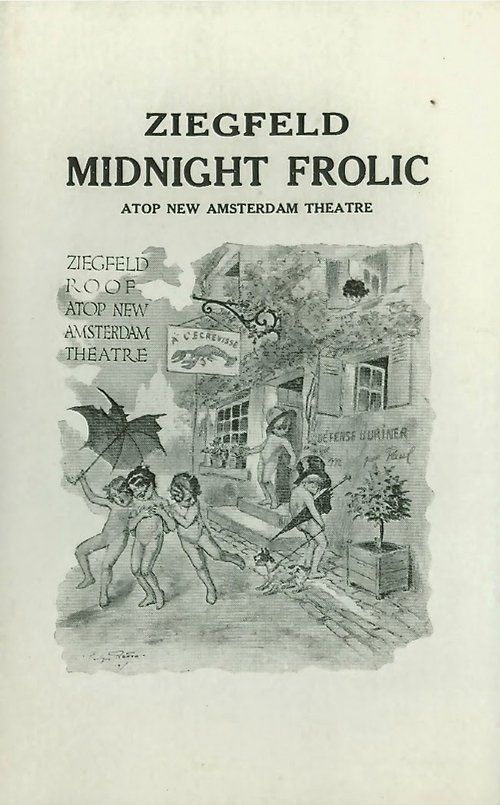

A Ziegfeld Midnight Frolic

"The Midnight Frolic - As You've Never Seen It Before!"

Plot

A Ziegfeld Midnight Frolic captures a lavish stage performance reminiscent of Florenz Ziegfeld's legendary rooftop shows, featuring Eddie Cantor performing in his signature blackface minstrel makeup. The film presents a series of musical numbers and comedic routines typical of the Ziegfeld revues, with Cantor as the central entertainer supported by performances from Richard Dix and Mary Eaton. The production showcases the opulent spectacle that made Ziegfeld's shows famous, including elaborate costumes, choreographed dance numbers, and sophisticated musical arrangements. Despite being filmed entirely on a Paramount soundstage rather than the actual Ziegfeld Theatre Roof Garden, the film successfully recreates the intimate, exclusive atmosphere of these midnight performances. The short film serves as both a preservation of Cantor's stage act and an early example of Hollywood's transition from silent to sound cinema.

Director

About the Production

This film was part of Paramount's early push into sound shorts, designed to showcase their new sound technology. The production recreated the Ziegfeld Theatre Roof Garden setting entirely on a soundstage, complete with artificial stars and moonlight effects. Eddie Cantor's blackface makeup, while standard for his stage performances at the time, was controversial even then and represents the problematic racial attitudes of the era. The film was shot using early sound-on-disc technology, which presented significant technical challenges for the cast and crew. Mary Eaton, a Broadway star, was making one of her rare film appearances, bringing authentic Ziegfeld glamour to the production.

Historical Background

A Ziegfeld Midnight Frolic was produced during a transformative period in American entertainment history. The year 1929 marked the full emergence of sound cinema, with studios scrambling to convert their facilities and talent to accommodate the new technology. The stock market crash of October 1929 occurred just months after this film's release, signaling the beginning of the Great Depression that would dramatically reshape American culture and entertainment preferences. The Ziegfeld theatrical empire itself was at its peak but would soon face financial challenges as the Depression deepened. This film represents the intersection of two entertainment worlds: the lavish Broadway theatrical tradition exemplified by Florenz Ziegfeld's productions, and the rapidly growing film industry that was beginning to lure theatrical talent to Hollywood. The practice of blackface performance, as seen with Eddie Cantor in this film, was still socially acceptable to mainstream white audiences in 1929, though it would increasingly face criticism in the coming decades. The film also reflects the Jazz Age's fascination with nightlife, spectacle, and escapism, themes that would become even more pronounced as audiences sought relief from economic hardships. Paramount's investment in East Coast production facilities like the Astoria studios demonstrated the industry's recognition of New York's importance as both a talent pool and market, though Hollywood would soon dominate film production almost entirely.

Why This Film Matters

A Ziegfeld Midnight Frolic holds cultural significance as a rare visual document of the Ziegfeld theatrical tradition, which had defined American popular entertainment in the 1910s and 1920s. The film captures the essence of an era when Broadway spectacles represented the pinnacle of American cultural sophistication, with their blend of beautiful women, elaborate costumes, and sophisticated musical numbers. As an early sound film, it exemplifies the transitional period when cinema was actively borrowing from established theatrical forms rather than developing its own unique language. The film also preserves Eddie Cantor's performance style, which would influence generations of comedians and entertainers, though his use of blackface makeup represents a problematic aspect of early 20th century entertainment that modern audiences find offensive. The short demonstrates how early sound technology was used to capture and preserve theatrical performances that might otherwise have been lost to history. It also illustrates the beginning of Hollywood's systematic recruitment of Broadway talent, a practice that would continue throughout the studio era. The film's recreation of the exclusive Midnight Frolics provides insight into the social world of New York's elite during the Jazz Age, where private performances and exclusive clubs were markers of social status. As a product of the pre-Code era, it represents a time before the Motion Picture Production Code would impose strict moral guidelines on American films, allowing for more adult themes and presentations that would soon be restricted.

Making Of

The production of A Ziegfeld Midnight Frolic took place during a pivotal moment in cinema history as the industry was rapidly transitioning from silent films to talkies. Paramount Pictures had invested heavily in sound equipment at their Astoria studios, making it one of the most advanced facilities on the East Coast. The filmmakers faced numerous technical challenges, including the need to keep cameras in soundproof booths and actors having to remain relatively stationary near microphones hidden on set. Director Joseph Santley, who had extensive experience in both stage and film, was chosen for his ability to bridge these two worlds. The recreation of the Ziegfeld Theatre Roof Garden was a remarkable feat of set design for its time, with the art department creating an artificial nighttime sky complete with twinkling stars and a painted moon backdrop. Eddie Cantor, accustomed to performing live before audiences, had to adapt his energetic stage style for the more intimate camera lens, though he retained much of his trademark physical comedy. The film was shot in just a few days, typical for short subjects of the era, with multiple takes required for each musical number due to the unforgiving nature of early sound recording. The production team worked closely with Ziegfeld's organization to ensure authenticity in costumes, choreography, and overall presentation, though the actual Florenz Ziegfeld had limited direct involvement in the film itself.

Visual Style

The cinematography of A Ziegfeld Midnight Frolic reflects the technical limitations and aesthetic approaches of early sound filmmaking. The camera work is relatively static compared to later musical films, constrained by the need to keep actors near the hidden microphones and the noisy cameras confined to soundproof booths. Cinematographer James Wong Howe, who was working at Paramount's Astoria studios during this period, may have been involved in creating the film's visual style, which emphasized clear, well-lit compositions suitable for the orthochromatic film stock of the era. The recreation of the nighttime Roof Garden setting required careful lighting design to simulate moonlight and create the illusion of an outdoor venue within the confines of a soundstage. The film uses medium shots and long shots primarily, with few close-ups, partly due to the limited mobility of the sound equipment and partly to showcase the full scope of the musical numbers. The cinematography successfully captures the glittering costumes and elaborate set design that were hallmarks of Ziegfeld productions, using lighting techniques to create depth and dimension in what was essentially a flat stage setting. The visual style represents a transitional moment between the more fluid camera work of late silent cinema and the more static compositions forced by early sound technology, before the development of more mobile sound recording equipment would allow for greater camera movement in later musical films.

Innovations

A Ziegfeld Midnight Frolic represents several important technical achievements in early sound cinema, particularly in the realm of recording musical performances. The film was produced using Paramount's early sound-on-disc system, which provided superior audio quality compared to contemporary sound-on-film processes, though it required cumbersome synchronization procedures. The production team successfully overcame the significant challenge of recording live musical performances in an era when microphones were large, insensitive, and had to be strategically hidden on set. The recreation of the Ziegfeld Theatre Roof Garden on a soundstage demonstrated advanced set design techniques for the period, including the use of painted backdrops and artificial lighting to simulate an outdoor nighttime environment. The film's relatively short runtime of 10 minutes was technically significant because it allowed for continuous recording without the need to change audio discs, which typically held only about 10 minutes of sound per side. The cinematography, while constrained by early sound equipment, still managed to capture the spectacle of the musical numbers through careful composition and lighting design. The production also represents an early example of the integration of Broadway talent and theatrical techniques into the new medium of sound film, a process that would become increasingly important as Hollywood developed the musical genre. The film's successful synchronization of complex musical numbers with visual performances demonstrated the growing sophistication of sound recording techniques in 1929, just a year after the introduction of talking pictures.

Music

The soundtrack of A Ziegfeld Midnight Frolic consists of several musical numbers typical of the Ziegfeld revue format, performed by Eddie Cantor, Mary Eaton, and Richard Dix. The music represents the sophisticated Tin Pan Alley style popular in the late 1920s, with jazz influences and elaborate orchestral arrangements. While specific song titles from this short are not well-documented, the musical numbers likely included popular standards of the era as well as original compositions written for Cantor's stage act. The sound recording was done using the early sound-on-disc system, which provided better audio quality than contemporary sound-on-film technology but required precise synchronization between the audio discs and the film projector. The musical arrangements were likely adapted from Cantor's stage shows, preserving his performance style for the new medium. Mary Eaton's numbers probably showcased her dancing abilities as well as her singing voice, representing the typical Ziegfeld girl presentation of feminine grace and talent. The orchestral accompaniment would have been provided by studio musicians familiar with the Broadway style, ensuring authenticity in the musical presentation. The soundtrack serves as an important historical record of the musical styles popular in late 1920s American entertainment, capturing the transition from the jazz age to the swing era that would follow. The audio quality, while impressive for its time, suffers from the limitations of early recording technology, including limited frequency range and occasional distortion, but remains clear enough to appreciate the performances.

Famous Quotes

No specific famous quotes are documented from this short film, as it was primarily a musical revue rather than a dialogue-driven narrative.

Memorable Scenes

- Eddie Cantor's opening number in blackface makeup performing his signature comedic songs and dances

- Mary Eaton's elegant dance routine showcasing the Ziegfeld girl style

- The recreation of the artificial starlit sky of the Roof Garden setting

- Richard Dix's musical performance demonstrating his versatility beyond dramatic roles

- The finale featuring all three performers in a spectacular ensemble number

Did You Know?

- Despite the title suggesting it was filmed at the Ziegfeld Theatre, the entire production was shot on a soundstage at Paramount's Astoria studios in Queens, New York.

- Eddie Cantor was one of the first major Broadway stars to successfully transition to sound films, and this short was designed to capitalize on his stage popularity.

- The film represents one of the earliest examples of a Broadway revue being adapted for the new sound medium.

- Paramount invested heavily in sound technology at their Astoria studios, making them a leading facility for early talkies produced on the East Coast.

- The Midnight Frolics were actually exclusive, invitation-only performances held after Ziegfeld's main shows, featuring more risqué content than the regular Follies.

- This film is one of the few visual records of what a Ziegfeld Midnight Frolic might have looked like, despite being a recreation.

- Richard Dix, primarily known as a dramatic actor, appears in this musical short demonstrating the versatility expected of early sound film actors.

- The film was released just as the Great Depression was beginning, making the escapist entertainment of Ziegfeld-style revues particularly appealing to audiences.

- Mary Eaton was a genuine Ziegfeld girl who had appeared in several actual Follies productions, bringing authenticity to the film.

- The short was likely designed to be shown as a supporting feature before main attractions, a common practice for early sound shorts.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of A Ziegfeld Midnight Frolic was generally positive, with reviewers praising the film's successful capture of the Ziegfeld atmosphere and Eddie Cantor's energetic performance. Variety noted that the film 'brings the glamour of Broadway to the screen with remarkable fidelity' and particularly commended the sound quality, which was still a novelty to many audiences. The New York Times mentioned that while the film couldn't fully replicate the experience of attending a live Midnight Frolic, it 'succeeds in preserving the essence of Cantor's stage magic for posterity.' Modern critics and film historians view the short as an important historical document, though they acknowledge its problematic elements, particularly Cantor's blackface performance. The film is often cited in studies of early sound cinema as an example of how the industry initially adapted theatrical content for the new medium rather than developing cinematic-specific material. Some contemporary scholars criticize the film as representative of Hollywood's early tendency to simply record stage performances rather than creating truly cinematic works, though others defend this approach as a necessary transitional step in the development of sound cinema. The preservation of Mary Eaton's performance is particularly valued by dance historians, as she represents the bridge between the Ziegfeld era and the later Hollywood musical.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception to A Ziegfeld Midnight Frolic in 1929 was generally enthusiastic, particularly among viewers who were familiar with Eddie Cantor's stage work and the Ziegfeld productions. The film offered many Americans their first opportunity to see the kind of exclusive entertainment typically reserved for New York's elite, making it a form of cultural democratization through cinema. Contemporary accounts suggest that audiences were particularly impressed with the sound quality, which was still a novelty in 1929, and the film's ability to capture the energy of a live performance. Cantor's fans were delighted to see their favorite performer preserved on film, though some noted that his manic energy was somewhat subdued compared to his live shows. The short subject format worked well as a supporting feature, providing audiences with a taste of Broadway glamour before the main presentation. Modern audiences viewing the film through archival screenings or home media often experience a mix of fascination with the historical spectacle and discomfort with the racial elements, particularly Cantor's blackface performance. Film enthusiasts and historians generally appreciate the film as a valuable time capsule, while casual viewers might find it dated in both style and content. The film serves as an educational tool about early sound cinema and theatrical traditions, though it requires contextualization about the racial attitudes of the period.

Awards & Recognition

- None recorded - short subjects were not typically eligible for major awards in 1929

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Ziegfeld Follies stage productions

- Broadway revue tradition

- Vaudeville performance style

- Eddie Cantor's stage act

- Paramount's early sound experiments

This Film Influenced

- The Hollywood Revue of 1929

- Show of Shows

- The Big Broadcast series

- Early MGM and Warner Bros. musical shorts

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of A Ziegfeld Midnight Frolic is uncertain, which is not uncommon for short subjects from this early sound period. Many films from 1929, particularly short subjects and musical revues, have been lost due to the unstable nitrate film stock used at the time and the perceived lower commercial value of shorts compared to feature films. The film may exist in archive collections, particularly at the Library of Congress or the UCLA Film & Television Archive, which hold many Paramount titles from this era. Some fragments or excerpts might survive as part of compilation films or documentary materials about early sound cinema. The film's historical value as a document of Eddie Cantor's early film work and the Ziegfeld tradition makes its preservation particularly important for film scholars and historians. If complete prints do survive, they would likely require restoration due to the deterioration common in films of this age. The sound-on-disc format presents additional preservation challenges, as both the film elements and the synchronized audio discs need to survive intact. Film preservation organizations have made efforts in recent decades to locate and restore early sound shorts, so it's possible that previously lost films like this one may yet be rediscovered in international archives or private collections.