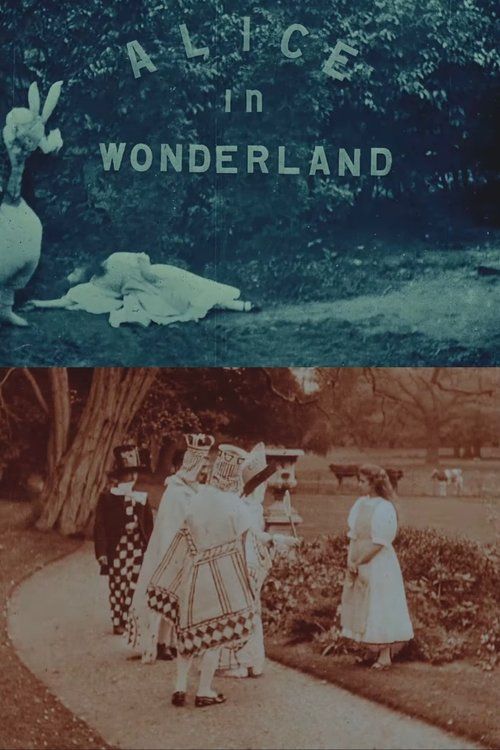

Alice in Wonderland

Plot

The film begins with Alice dozing in a garden while reading a book. She is suddenly awakened by a White Rabbit, dressed in a waistcoat and carrying a pocket watch, who exclaims that he is late. Intrigued, Alice follows the rabbit down a rabbit hole and finds herself in a strange hall with many doors. She encounters various characters including the Cheshire Cat, the Mad Hatter, and the Queen of Hearts. The film showcases several key scenes from the book, including the Mad Hatter's tea party and the Queen's croquet game. The narrative concludes with Alice awakening, suggesting the entire adventure may have been a dream, though the ending of the original film is lost.

About the Production

This was one of the most ambitious British films of its time, requiring elaborate costumes, sets, and special effects. The production used multiple cameras and innovative techniques for the era, including superimposition for the Cheshire Cat's appearance and disappearance. The film required extensive makeup and prosthetics for the various characters, which was quite advanced for 1903.

Historical Background

This film was produced during the very early days of narrative cinema, when films were transitioning from simple novelty shorts to more complex storytelling. In 1903, the British film industry was still in its infancy, competing with the more established French and American markets. The film was made just six years after the first public film screenings, at a time when most films lasted only a minute or two. This period saw the emergence of film as a legitimate art form and entertainment medium, with directors beginning to explore longer narratives and more sophisticated techniques. The Edwardian era in Britain was characterized by technological optimism and cultural exploration, making it an ideal time for adapting such a fantastical story.

Why This Film Matters

As the first film adaptation of one of English literature's most beloved works, this film holds a unique place in cinema history. It demonstrated that complex literary works could be adapted to the new medium of film, paving the way for future literary adaptations. The film's ambitious scope and technical innovations helped establish British cinema as a serious artistic endeavor. Its existence shows that even in cinema's earliest days, filmmakers recognized the commercial and artistic potential of adapting classic literature. The film's partial survival and restoration have made it an invaluable artifact for film historians and scholars studying early narrative cinema techniques.

Making Of

The production of this 1903 adaptation was a monumental undertaking for the British film industry. Cecil Hepworth, one of Britain's film pioneers, invested heavily in the project, creating elaborate costumes and sets that were unprecedented for British cinema at the time. The filming process was arduous, with actors having to perform under hot studio lights while wearing heavy, restrictive costumes. The special effects, particularly the Cheshire Cat's appearance and disappearance, required multiple exposures and careful planning. The cast was primarily composed of Hepworth's regular troupe of actors, with his wife Margaret Hepworth (credited as Mrs. Hepworth) playing multiple roles. The film's production took several weeks, an unusually long period for films of this era, which were typically shot in just a few days.

Visual Style

The cinematography, attributed to Percy Stow and possibly Cecil Hepworth himself, employed several innovative techniques for the era. The film used multiple camera angles, which was uncommon in 1903, and incorporated special effects through superimposition and double exposure. The lighting was carefully planned to create the fantastical atmosphere of Wonderland, with the studio lights manipulated to suggest magical transformations. The camera work was static, as was typical of the period, but the composition within each frame was carefully considered to maximize the visual storytelling.

Innovations

The film showcased several technical innovations for its time, including the use of superimposition for the Cheshire Cat's appearances and disappearances, multiple exposure techniques for magical effects, and elaborate makeup and prosthetics that were advanced for 1903. The production also utilized multiple cameras and careful editing to create a coherent narrative, which was still a relatively new concept in cinema. The hand-coloring of some prints demonstrated an early attempt to add visual appeal to the black and white footage.

Music

As a silent film, it would have been accompanied by live music during exhibition. The specific musical scores used are not documented, but it would have typically been accompanied by a pianist or small orchestra playing popular tunes of the era or classical selections appropriate to the mood of each scene. Modern screenings of the restored version often feature newly composed scores or period-appropriate music.

Famous Quotes

Oh dear! Oh dear! I shall be too late! - The White Rabbit

Who are you? - Alice to the Caterpillar

Off with their heads! - The Queen of Hearts

We're all mad here. - The Cheshire Cat

Curiouser and curiouser! - Alice

Memorable Scenes

- Alice following the White Rabbit down the rabbit hole

- The Mad Hatter's tea party with its chaotic energy

- The Cheshire Cat appearing and disappearing using superimposition effects

- The Queen of Hearts' croquet game using flamingos as mallets

- Alice's transformation in size after eating the cake and drinking from the bottle

Did You Know?

- This was the very first film adaptation of Lewis Carroll's 'Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'

- The film was originally 12 minutes long, which was considered feature-length for 1903

- Only about 8 minutes of the film survive today, with the beginning and end portions lost

- The surviving footage was discovered in 2009 and restored by the British Film Institute

- Director Cecil Hepworth also played the role of the Frog Footman in the film

- May Clark, who played Alice, was only 16 years old at the time of filming

- The film used early special effects including superimposition and multiple exposure techniques

- It was one of the most expensive British films produced in 1903 due to its elaborate costumes and sets

- The Mad Hatter's tea party scene was filmed using a single continuous take, which was technically challenging for the time

- The film was hand-colored in some prints, a common practice for important films of this era

- The White Rabbit's costume was so elaborate that the actor had difficulty moving and seeing

- The film was shot entirely indoors at Hepworth's studio, even for the garden scenes

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews of the film were generally positive, with critics praising its ambition and technical achievements. The trade journal 'The Optical Magic Lantern Journal and Photographic Enlarger' noted the film's 'remarkable success' in bringing Carroll's fantasy to life. Modern critics and film historians view the surviving footage as an important historical document that showcases early cinematic techniques and the nascent art of film adaptation. The British Film Institute's restoration has been widely praised for making this important piece of film history accessible to modern audiences.

What Audiences Thought

The film was reportedly popular with audiences upon its release, who were fascinated by its visual spectacle and the novelty of seeing a beloved story brought to life on screen. Contemporary accounts suggest that audiences were particularly impressed by the special effects and elaborate costumes. The film's length, while substantial for the period, was not seen as excessive, and it was frequently programmed as a featured attraction in music halls and early cinemas. Modern audiences viewing the restored footage often express amazement at the sophistication of the production given its 1903 date.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Lewis Carroll's 'Alice's Adventures in Wonderland' (1865)

- Lewis Carroll's 'Through the Looking-Glass' (1871)

- Stage adaptations of Alice in Wonderland from the late 19th century

This Film Influenced

- Alice in Wonderland (1915)

- Alice in Wonderland (1931)

- Alice in Wonderland (1933 Disney animated short)

- Alice in Wonderland (1951 Disney)

- Alice in Wonderland (1972)

- Alice in Wonderland (2010 Tim Burton)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was considered partially lost for many decades. In 2009, a severely damaged but complete print was discovered by the British Film Institute. The BFI undertook an extensive restoration project, digitally repairing the damaged nitrate film and reconstructing the surviving 8 minutes. The original 12-minute version remains incomplete, with the beginning and ending portions still lost. The restored footage is now preserved in the BFI National Archive and has been made available for public viewing.