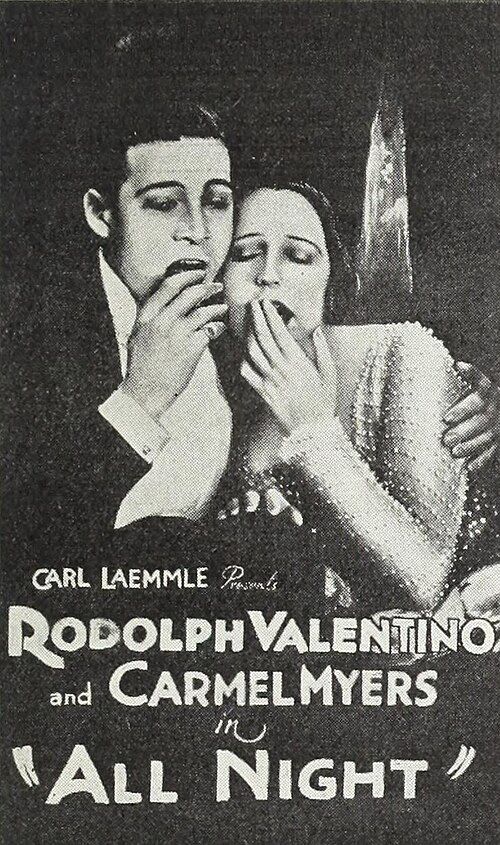

All Night

Plot

In this 1918 silent comedy-drama, a wealthy married society couple decides to play a prank by swapping roles with their servants for a night. They persuade an unmarried pair, portrayed by Rudolph Valentino and Carmel Myers, to impersonate them at a high-society party while the married couple pretends to be the servants. The situation leads to romantic complications and social misunderstandings as the imposters navigate the upper-class gathering. The film explores themes of class identity and social pretense through its role-reversal premise. As the night progresses, the boundaries between servants and masters blur, creating comedic situations and revealing true characters.

About the Production

This was one of Rudolph Valentino's early films before his breakthrough stardom in 1921's 'The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.' The film was produced during the height of World War I, when the film industry was experiencing significant changes. Bluebird Photoplays was Universal's brand for more sophisticated and upscale productions, often featuring romantic comedies and dramas aimed at middle-class audiences.

Historical Background

1918 was a pivotal year in world history, marking the final year of World War I and the height of the devastating Spanish Flu pandemic. The American film industry was transitioning from the early pioneer days to a more structured studio system. Universal, under Carl Laemmle's leadership, was competing with other major studios by creating specialized brands like Bluebird Photoplays. The film industry was also facing censorship challenges from various state and local boards, which influenced content decisions. This period saw the rise of the feature film format over short subjects, and Hollywood was establishing itself as the global center of film production. The war had restricted European film imports, creating opportunities for American films to dominate international markets.

Why This Film Matters

While not a major commercial success, 'All Night' represents an important milestone in Rudolph Valentino's early career trajectory before he became one of silent cinema's biggest stars. The film exemplifies the class-reversal comedy genre popular in the late 1910s, which often used humor to comment on social stratification in American society. As a Universal Bluebird production, it reflects the studio's strategy of producing sophisticated yet accessible content for middle-class audiences. The film's disappearance makes it part of the tragic legacy of lost silent films, with estimates suggesting that 75-90% of silent films are gone forever. Its existence in film history, despite being lost, contributes to our understanding of Valentino's development as an actor and the types of roles he played before his typecasting as the 'Latin Lover.'

Making Of

The production took place at Universal City studios during a period of rapid expansion for the facility. Paul Powell, the director, was known for his efficient shooting methods and ability to extract strong performances from his actors. Valentino, still honing his screen persona, was reportedly enthusiastic about the role-reversal premise. Carmel Myers, already an established Universal star, helped guide the less experienced Valentino through the production. The film was shot on a modest budget typical of Universal's Bluebird productions, with interior sets constructed to represent upscale society homes. The production team faced the challenges common to 1918 filmmaking, including limited lighting technology and the need for clear visual storytelling without dialogue.

Visual Style

As a 1918 Universal production, the film would have utilized the standard cinematographic techniques of the late silent era. The cinematographer likely employed static camera positions with occasional tracking shots using dollies or cranes. Lighting would have been primarily artificial studio lighting, with the emerging use of diffused lighting techniques to create softer, more romantic images. Universal was known for its relatively high production values compared to smaller studios, so the film likely featured well-composed shots and careful attention to visual storytelling. The film stock would have been orthochromatic, which was sensitive to blue and green light but not red, affecting how actors' complexions appeared on screen and requiring specific makeup techniques.

Innovations

The film employed standard technical practices for 1918 Universal productions without notable innovations. The studio was known for its efficient production methods and consistent technical quality across its releases. The film would have been shot on 35mm film stock with an aspect ratio of approximately 1.33:1, standard for the era. Universal had recently improved its studio lighting systems, allowing for more sophisticated visual effects and better exposure control. The film's title cards would have been created by Universal's art department, which was known for its elegant intertitles. While not technically groundbreaking, the film represented Universal's commitment to professional production values in its Bluebird lineup.

Music

As a silent film, 'All Night' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during theatrical exhibition. Universal typically provided cue sheets with suggested musical selections for their theater organists or small orchestras. The score would have included popular songs of 1918, classical pieces, and specially composed mood music to match the on-screen action. For a comedy-drama with romantic elements, the music would have ranged from light, playful themes during comedic scenes to more romantic melodies for the intimate moments. Universal's music department, led by Sam Kaylin, would have prepared these musical suggestions, though individual theaters often adapted them based on their available musicians and local preferences.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening scene where the society couple convinces Valentino and Myers to switch places

- The party sequence where the imposters must navigate high society etiquette

- The comedic moments when the real servants must act as masters

- The romantic developments between the switched couples

- The final revelation scene where the truth is revealed

Did You Know?

- This film is considered lost, with no known surviving copies in any film archives or private collections.

- Rudolph Valentino was not yet the famous Latin Lover he would become; this was one of approximately 20 films he appeared in before achieving stardom.

- Director Paul Powell was a prominent director at Universal who would later direct Mary Pickford in several films.

- Carmel Myers was one of Universal's leading actresses during this period and would later have a successful career in talking pictures.

- The film was released just three months before the end of World War I, during a time when American film production was expanding rapidly.

- Bluebird Photoplays was Universal's premium brand, distinguished by their blue tinted film leader and higher production values.

- The film's theme of class reversal was a popular trope in silent comedies of the late 1910s.

- Charles Dorian, who played the husband, was a character actor who appeared in over 200 films between 1915 and 1940.

- The film was released during the Spanish Flu pandemic, which affected theater attendance across the United States.

- This was one of the last films Valentino made before signing with Famous Players-Lasky, where he would achieve his greatest fame.

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews from 1918 were generally positive but not enthusiastic, typical of the reception Universal's Bluebird productions received. The Motion Picture News praised the film's 'amusing situations' and noted that Valentino showed 'considerable promise' in his role. Variety mentioned that the plot, while familiar, was executed with 'considerable skill and humor.' Modern critics cannot evaluate the film directly due to its lost status, but film historians reference it as an example of Valentino's early work and Universal's production values during the silent era. Retrospective assessments focus more on its historical significance than its artistic merits, given that no prints survive for evaluation.

What Audiences Thought

The film performed modestly at the box office during its 1918 release, meeting but not exceeding Universal's expectations for a Bluebird production. Audience attendance was likely affected by the ongoing Spanish Flu pandemic, which caused many theaters to close or operate at reduced capacity. Contemporary trade papers reported that audiences found the role-reversal premise entertaining, and Valentino's performance received favorable mentions in viewer letters to film magazines. The film's appeal was primarily to middle-class theater-goers who formed the core audience for Universal's Bluebird brand. Unlike Valentino's later films, which attracted passionate fan mail and created a sensation among female viewers, 'All Night' generated only mild audience interest, as Valentino had not yet developed his star persona.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Plautine comedy traditions

- Shakespearean comedies with mistaken identity

- Earlier American comedy films with servant-master themes

- European farce traditions

This Film Influenced

- Later films with role-reversal themes

- Universal's subsequent Bluebird productions

- Other Valentino films that explored social themes

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Lost film - no known copies survive in any film archives or private collections. The film is listed as lost by the American Film Institute and is among the approximately 75% of silent films that are considered lost forever. No fragments, trailers, or publicity stills from the film are known to exist.