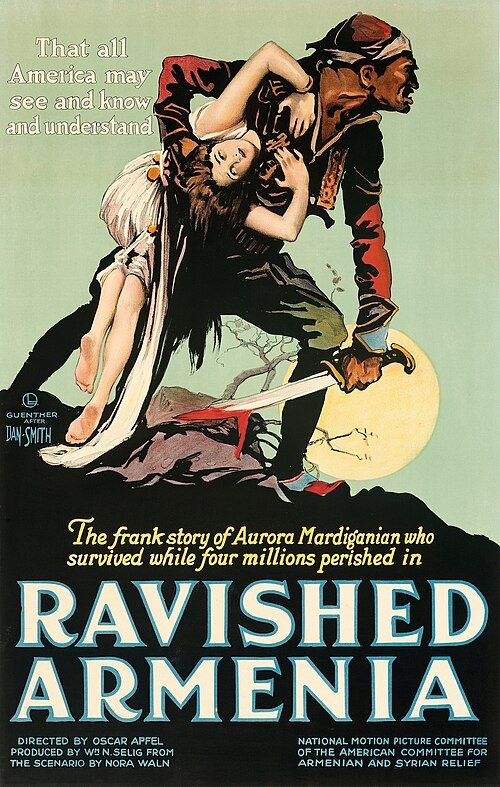

Auction of Souls

"The Story of a Real Girl Who Lived Through the Armenian Atrocities"

Plot

Auction of Souls tells the harrowing true story of Aurora Mardiganian, a young Armenian woman who survives the horrific Armenian Genocide perpetrated by the Ottoman Empire during World War I. The film follows Aurora's journey from her peaceful life in the Armenian town of Tchemesh-Gedzak to being forced into a death march through the Syrian desert, witnessing the massacre of her family and fellow Armenians. She endures unimaginable suffering including being sold into a Turkish harem, forced conversion to Islam, and multiple escape attempts while maintaining her faith and determination to survive. The narrative culminates in her eventual escape to America where she becomes an advocate for Armenian genocide recognition, with the film itself serving as a powerful testament to the atrocities she witnessed. Through Aurora's portrayal of herself, the film provides an unflinching look at one of history's most horrific crimes against humanity.

About the Production

The film was produced as a fundraising vehicle for the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief, with proceeds going to help Armenian survivors. Aurora Mardiganian, who was actually a genocide survivor, insisted on performing her own stunts, including dangerous scenes of falling from cliffs and being dragged through rough terrain. The production employed over 3,000 extras, many of whom were actual Armenian refugees living in California at the time. Director Oscar Apfel faced significant challenges recreating the genocide scenes while maintaining sensitivity to the real victims, and the film was shot in secrecy to avoid diplomatic protests from the Ottoman government.

Historical Background

Auction of Souls was produced in the immediate aftermath of World War I and the Armenian Genocide (1915-1917), during a period when the world was first learning about the systematic extermination of 1.5 million Armenians by the Ottoman Empire. The film emerged during the American Red Cross and Near East Relief's massive humanitarian campaigns to aid survivors. At the time of its release, the Treaty of Versailles was being negotiated, and there was significant international debate about recognizing the Armenian Genocide and holding perpetrators accountable. The United States had not yet officially recognized the genocide, though American diplomats like Henry Morgenthau had extensively documented the atrocities. The film served as both historical documentation and propaganda for the Armenian relief cause, arriving at a crucial moment when public awareness could influence international policy. Its production coincided with the rise of American cinema as a powerful medium for shaping public opinion and social consciousness.

Why This Film Matters

Auction of Souls represents a landmark in cinema history as the first feature film to address genocide as its central theme, establishing a precedent for using film as a tool for bearing witness to atrocities. It pioneered the concept of survivor testimony in cinema, with an actual victim portraying her own experiences decades before Holocaust documentaries would popularize this format. The film's existence challenged the emerging Hollywood studio system's avoidance of controversial political content, proving that commercial cinema could tackle difficult historical subjects. It also established the template for what would later be called 'atrocity films' - works that document and condemn crimes against humanity. The film's use as a fundraising tool demonstrated cinema's potential for humanitarian advocacy, influencing later documentary and narrative films addressing social injustices. Its loss and partial preservation have made it a symbol of cultural memory and the importance of film preservation, especially for historical documentation of human rights violations.

Making Of

The making of Auction of Souls was as extraordinary as its subject matter. Aurora Mardiganian, who had escaped Armenia and arrived in America in 1917, was discovered by a Hollywood screenwriter who helped her publish her memoirs 'Ravished Armenia.' The book became a bestseller and was quickly adapted into this film. Mardiganian insisted on playing herself, despite having no acting experience, and underwent extensive preparation including learning blocking and camera techniques. The production faced numerous challenges, including finding appropriate locations to stand in for the Armenian landscape, casting thousands of extras for massacre scenes, and recreating horrific events with sensitivity. Many Armenian refugees living in California were hired as extras and consultants, bringing authentic experience to the production. The film's most controversial scenes, including the crucifixion of Armenian girls, were based on Mardiganian's eyewitness testimony, though some critics at the time accused the filmmakers of exaggeration for dramatic effect.

Visual Style

The cinematography, handled by Lucien Andriot, employed techniques typical of late silent era dramatic films but with documentary-like attention to detail. The film utilized location shooting in the San Bernardino Mountains to approximate the Armenian landscape, creating a sense of authenticity unusual for the period. Battle and massacre scenes featured wide shots with hundreds of extras, demonstrating impressive scale for an independent production. Close-ups of Aurora Mardiganian were used effectively to convey personal trauma and suffering. The surviving footage shows sophisticated use of lighting to create dramatic contrast between peaceful Armenian village life and the darkness of the genocide. The camera work in action sequences, including chase scenes and falls, appears more dynamic than typical for 1919, possibly reflecting the influence of Mardiganian's real experiences in making the action feel authentic.

Innovations

Auction of Souls pioneered several technical approaches for its time, particularly in the realm of historical reenactment and documentary-style narrative filmmaking. The production employed innovative techniques for staging large-scale massacre scenes involving thousands of extras, using multiple cameras to capture different perspectives of the same events. The film's use of actual Armenian refugees as extras and consultants represented an early form of what would later be called 'authentic casting' in historical films. The technical crew developed special effects for depicting crucifixion scenes and mass executions that were realistic for the period while avoiding excessive gore. The film's most significant technical achievement was its successful integration of documentary testimony with narrative cinema, creating a hybrid form that would influence later historical films and documentaries.

Music

As a silent film, Auction of Souls would have featured live musical accompaniment during theatrical screenings. The original score has been lost, but typical practice for dramatic films of this era would have included classical selections, popular songs, and original compositions tailored to the on-screen action. For the 2009 restored version, a new score was commissioned featuring traditional Armenian music combined with contemporary classical elements to bridge the historical and modern viewing experience. The restored soundtrack incorporates instruments like the duduk, kemancha, and zurna to authentically represent Armenian musical culture. The original 1919 screenings likely varied in musical quality depending on the theater's resources, with larger venues employing full orchestras while smaller houses used piano or organ accompaniment.

Famous Quotes

'I have seen with my own eyes what no human being should ever have to see' - Aurora Mardiganian's opening narration

'They took everything from us except our memory' - from the film's intertitles

'To survive is not enough; we must bear witness' - closing intertitle

'Even in the darkest night, the Armenian spirit burns bright' - intertitle during crucifixion scene

'This is not entertainment; this is testimony' - promotional tagline used in original marketing

Memorable Scenes

- The opening peaceful village scenes showing Armenian life before the genocide

- The death march through the desert with thousands of starving refugees

- The crucifixion scene where Armenian girls are nailed to crosses

- Aurora's escape from the Turkish harem and subsequent flight through mountains

- The auction scene where young Armenian women are sold to Turkish buyers

- The final scenes of Aurora's arrival in America and her commitment to testimony

Did You Know?

- Auction of Souls is considered the first film ever made about genocide, predating Holocaust documentaries by decades

- Aurora Mardiganian was paid $50 per week for her role and received no royalties despite the film's success

- The film was also released under the title 'Ravished Armenia' and sometimes shown as 'Auction of Souls: Ravished Armenia'

- Mardiganian claimed the crucifixion scene was based on real events where Turkish forces actually crucified Armenian girls

- The film was banned in several countries including Turkey and faced diplomatic protests from the Ottoman government

- Henry Morgenthau Sr., former U.S. Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, served as an advisor to ensure accuracy

- Mardiganian later wrote in her memoir that filming the reenactments was as traumatic as experiencing the real events

- The film was used as a fundraising tool, raising millions for Armenian relief efforts

- A complete copy was discovered in Soviet Armenia in the 1990s, but only one reel survived in watchable condition

- The film's title 'Auction of Souls' refers to the scene where Armenian girls were sold at auction in Turkish markets

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception was mixed but generally respectful of the film's intentions. The New York Times praised its 'powerful and moving' depiction of Armenian suffering while noting its 'harrowing' nature might be too intense for general audiences. Variety called it 'a significant contribution to the historical record' though criticized some scenes as 'overly melodramatic.' Some critics questioned whether such horrific events should be depicted in entertainment cinema, while others defended it as necessary documentation. Modern critics, viewing only the surviving fragments, recognize it as an important historical artifact despite its lost status. Film historians consider it groundbreaking for its early attempt at cinematic testimony and its role in bringing international attention to the Armenian Genocide. The surviving 24-minute version has been praised at film festivals for its historical importance and raw power, with critics noting how even these brief fragments convey the magnitude of the atrocities depicted.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception in 1919 was deeply divided along geographical and ethnic lines. Armenian communities worldwide embraced the film as validation of their suffering and attended screenings in large numbers, often organizing group viewings. American audiences in areas with large Armenian populations showed strong support, while general audiences in other regions were often shocked by the graphic content. Some theaters reported walkouts during the most intense scenes, while others noted audiences sitting in stunned silence. The film proved particularly effective as a fundraising tool, with many viewers donating to Armenian relief causes after screenings. In contrast, Turkish and Ottoman sympathizers protested the film and organized boycotts where possible. Modern audiences viewing the restored fragments report being deeply moved by the historical significance and the authenticity of Aurora Mardiganian's performance, though many express frustration that the complete film is lost to history.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- D.W. Griffith's 'The Birth of a Nation' (1915) for epic scale

- Cecil B. DeMille's historical epics for dramatic reenactment

- Contemporary newsreels for documentary approach

- Stage melodramas for emotional storytelling

- Early documentary films for factual presentation

This Film Influenced

- Holocaust documentaries of the 1940s-1960s

- Schindler's List (1993) for survivor testimony

- The Killing Fields (1984) for genocide depiction

- Hotel Rwanda (2004) for contemporary genocide storytelling

- Armenian Genocide documentaries and feature films

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The complete film is considered lost, with only fragments surviving. A single 35mm reel was discovered in Soviet Armenia in the 1990s, containing approximately 24 minutes of footage. This reel was preserved by the Armenian Genocide Resource Center of Northern California and digitally restored in 2009. The restored footage represents roughly one-quarter to one-third of the original film. No other complete copies are known to exist, though some still photographs and promotional materials survive. The film represents one of the most significant losses of silent era cinema due to its historical importance as the first genocide film. Preservation efforts continue through various film archives and Armenian cultural institutions, but the chances of finding additional footage grow increasingly remote.