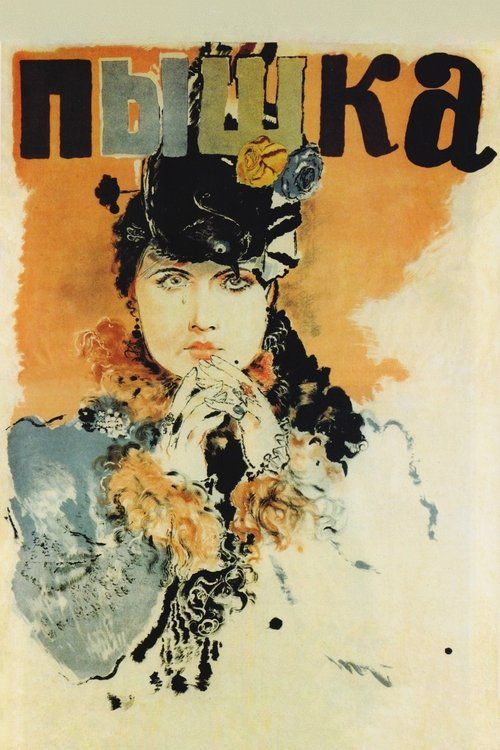

Boule de Suif

Plot

Set during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, this Soviet adaptation follows a diverse group of French bourgeois travelers fleeing occupied Rouen in a stagecoach. Among them is Elisabeth Rousset, a young courtesan nicknamed 'Boule de Suif' (Ball of Fat) by the other passengers who initially scorn her despite her generosity in sharing food. When their journey is halted by Prussian forces at an inn, the travelers learn they can only proceed if Boule de Suif agrees to spend the night with the Prussian commander. The hypocritical passengers, who had condemned her profession, now pressure her to sacrifice herself for their freedom, revealing the stark contrast between their moral pretensions and true selfish nature. After she complies for their sake, they immediately revert to shunning her, leaving her isolated and betrayed while they continue their journey.

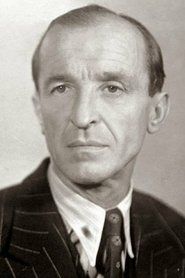

About the Production

This was one of Mikhail Romm's directorial debut films, made during the early sound era of Soviet cinema. The production faced challenges in creating authentic 19th-century French settings within Soviet constraints, requiring detailed set construction and costume design. The film was notable for its early use of sound technology in Soviet cinema, with careful attention to dialogue and ambient sounds to enhance the dramatic tension.

Historical Background

Produced in 1934, during the early years of Stalin's regime and the First Five-Year Plan, this film emerged at a complex moment in Soviet cultural history. While Socialist Realism was being established as the official artistic doctrine, this adaptation of Western literature demonstrated a brief window of artistic flexibility. The film's critique of bourgeois hypocrisy resonated with Soviet ideological themes, though its focus on individual moral struggle rather than class revolution was unusual for the period. The choice of Maupassant's work reflected the Soviet Union's complicated relationship with Western culture - condemning capitalist society while acknowledging its artistic achievements. The film's production coincided with the Soviet film industry's transition to sound, making it technically innovative for its time.

Why This Film Matters

This film marked a significant milestone in Soviet cinema as one of the most successful adaptations of Western literature during the Stalin era. It demonstrated that Soviet filmmakers could engage with foreign texts while maintaining ideological relevance, using Maupassant's critique of bourgeois hypocrisy to align with Soviet values. The film's psychological depth and character development influenced subsequent Soviet narrative cinema, moving beyond purely propagandistic storytelling. It also established Mikhail Romm as a major directorial talent who would go on to create other significant works. The film's success proved that Soviet audiences would respond to sophisticated, morally complex narratives, paving the way for more artistically ambitious productions within the constraints of the system.

Making Of

Mikhail Romm, previously a screenwriter, fought to direct this adaptation as his first feature. The casting of Galina Sergeyeva as Boule de Suif was controversial at the time, as she was relatively unknown, but Romm insisted on her after seeing her dramatic range in theater auditions. The film was shot during a particularly harsh winter in Moscow, with the cast enduring cold conditions on the constructed sets. The famous inn scene where the moral dilemma unfolds required extensive rehearsals to achieve the precise timing and emotional intensity Romm demanded. The production team consulted French cultural experts to ensure authenticity in costumes, props, and social customs of the period. The sound recording presented technical challenges, as the Soviet studios were still mastering dialogue recording, leading to innovative microphone placement techniques.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Boris Volchek employed innovative techniques for early Soviet sound cinema, using dramatic lighting to emphasize the psychological states of the characters. The confined space of the stagecoach was filmed using creative camera angles to create a sense of claustrophobia and tension. The contrast between the dark, shadowy interiors and the bleak winter exterior enhanced the film's moral atmosphere. Volchek's use of close-ups, particularly on Sergeyeva's face during her moral crisis, was groundbreaking for Soviet cinema of the period. The film's visual style balanced realistic period detail with expressionistic lighting to underscore the emotional drama.

Innovations

The film was notable for its early mastery of sound recording technology in Soviet cinema, particularly in capturing dialogue within confined spaces. The production developed innovative techniques for simulating stagecoach movement while maintaining stable camera work and clear sound. The film's editing, particularly in the tense confrontation scenes, demonstrated sophisticated understanding of rhythm and pacing for sound cinema. The costume and set design teams achieved remarkable period authenticity within Soviet production constraints. The film's success in creating a convincing 19th-century French atmosphere using Soviet resources and locations was considered a significant technical achievement.

Music

The musical score was composed by Gavriil Popov, who created a soundtrack that blended French-inspired melodies with Soviet musical sensibilities. The film's sound design was particularly innovative for its time, using ambient sounds of the stagecoach journey and winter weather to create atmospheric depth. The dialogue recording was technically advanced for Soviet cinema of 1934, with clear audio capture even in group scenes. The score used leitmotifs to represent different characters, particularly a melancholic theme for Boule de Suif that evolved throughout the narrative. The music emphasized the film's moral themes without being overly didactic, a delicate balance in Soviet cinema of the era.

Famous Quotes

When society needs a sacrifice, it always finds someone expendable

Your principles are flexible when your comfort is at stake

She fed us all when we were hungry, yet we condemn her for how she earns her bread

In war, the first casualty is not truth, but compassion

Memorable Scenes

- The tense scene in the inn where passengers pressure Boule de Suif to sacrifice herself, revealing their true moral character

- The opening stagecoach journey establishing the social hierarchy and tensions among the travelers

- Boule de Suif's emotional breakdown after realizing her sacrifice has earned her only contempt

- The final shot of the abandoned Boule de Suif watching the stagecoach depart, emphasizing her isolation

Did You Know?

- This was director Mikhail Romm's feature film debut, launching his distinguished career in Soviet cinema

- The film was one of the earliest Soviet adaptations of Western literature, specifically French author Guy de Maupassant

- Galina Sergeyeva's performance as Boule de Suif was considered groundbreaking for its psychological depth and emotional range

- The film's title in Russian is 'Пышка' (Pyshka), which literally means 'bun' or 'fatty roll'

- Despite being a Soviet production, the film maintained remarkable fidelity to Maupassant's original French setting and social critique

- The stagecoach scenes were filmed using a specially constructed movable set to simulate the journey

- The film was initially praised for its technical achievements in sound recording and cinematography

- It was among the first Soviet films to explore complex moral ambiguity rather than clear-cut revolutionary themes

- The Prussian uniforms and military details were meticulously researched for historical accuracy

- The film's release coincided with a period of increased cultural exchange between the Soviet Union and Western Europe

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film for its technical mastery and faithful adaptation of Maupassant's work, with particular acclaim for Galina Sergeyeva's nuanced performance. Western critics at international film festivals noted the film's sophisticated approach to moral themes and its high production values. Later Soviet film historians recognized it as a landmark achievement in early sound cinema and as Romm's breakthrough work. Modern critics have reevaluated the film as a masterful example of how Soviet directors could work within ideological constraints to create artistically significant cinema. The film is now regarded as one of the most successful Soviet adaptations of foreign literature from the 1930s.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by Soviet audiences upon its release, who appreciated its dramatic tension and the moral complexity of the story. Many viewers connected with the theme of social hypocrisy, which resonated with their own experiences under the Soviet system. The film ran successfully in Soviet theaters for several months, unusual for a non-revolutionary themed production. In later years, it became a cult classic among Soviet cinema enthusiasts, particularly admired for Sergeyeva's performance and Romm's direction. International audiences at film festivals responded positively to the universal themes of moral compromise and social pressure.

Awards & Recognition

- Stalin Prize, Second Class (1935)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Guy de Maupassant's original short story (1880)

- French realist literature tradition

- Early Soviet psychological cinema

- German expressionist visual techniques

This Film Influenced

- Later Soviet adaptations of Western literature

- Mikhail Romm's subsequent films including 'Lenin in October' and 'Dream'

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved in the Gosfilmofond archive in Russia and has undergone digital restoration. Original nitrate elements were carefully preserved and transferred to safety stock in the 1970s. A restored version was released on DVD as part of the Mikhail Romm collection in the early 2000s.