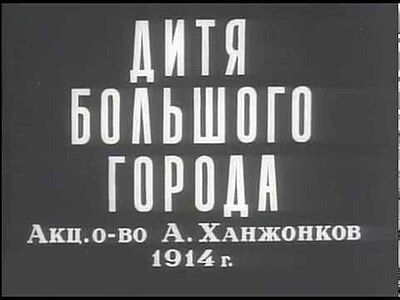

Child of the Big City

Plot

Mary, a young seamstress working in a grimy sweatshop, dreams of escaping her impoverished life for the glamour and luxury of the upper class. Her aspirations are realized when she catches the eye of Victor, a wealthy bourgeois man who sweeps her into a life of extravagance and indulgence. However, Mary quickly grows bored with Victor and his lifestyle, systematically draining his finances through her lavish spending and materialistic demands. When Victor, now nearly bankrupt, suggests they leave the city for a simpler life where his remaining money might sustain them, Mary coldly rejects him and immediately seeks out a new wealthy benefactor. A year later, Victor is found living in squalor in a cold, dilapidated room, still hopelessly pining for the woman who destroyed his life.

About the Production

The film was produced by Alexander Khanzhonkov's company, which was the leading film studio in pre-revolutionary Russia. Bauer was known for his meticulous attention to detail and innovative camera techniques, which were evident in this production. The film was shot on location in Moscow, utilizing both studio sets and actual city locations to contrast the wealthy and working-class environments.

Historical Background

The film was produced in 1914, a pivotal year in Russian and world history. This was during the final years of the Russian Empire under Tsar Nicholas II, a period marked by rapid industrialization, growing social unrest, and increasing tensions between the aristocracy and working classes. The film's themes of social mobility and moral corruption reflected the anxieties of a society in transition. Moscow, where the film was shot, was experiencing massive urbanization, with thousands of workers like Mary moving from rural areas to work in factories and sweatshops. The film was released just as World War I was beginning, which would eventually lead to the Russian Revolution in 1917 and fundamentally transform Russian society and cinema. The pre-revolutionary Russian film industry was surprisingly sophisticated, producing hundreds of films annually that competed with European productions in quality and innovation.

Why This Film Matters

'Child of the Big City' represents a significant milestone in early Russian cinema's exploration of social themes and psychological drama. Director Yevgeni Bauer was instrumental in developing a uniquely Russian cinematic language that emphasized psychological depth and social commentary. The film's portrayal of urban life and social mobility anticipated many of the themes that would become central to Soviet cinema in the 1920s and 1930s. Bauer's innovative visual techniques and sophisticated narrative structures influenced generations of Russian filmmakers, including Soviet masters like Sergei Eisenstein and Vsevolod Pudovkin. The film is also notable for its early feminist undertones, presenting a female character who actively pursues her desires and manipulates the patriarchal power structure, albeit through morally questionable means. This psychological complexity in character development was rare in cinema of this period and demonstrated the artistic maturity of pre-revolutionary Russian film.

Making Of

The film was created during the golden age of Russian silent cinema, when the Khanzhonkov Company was producing dozens of films annually. Yevgeni Bauer, known for his perfectionism and artistic vision, worked closely with his actors to achieve the psychological depth characteristic of his films. The production utilized both studio sets and location shooting in Moscow to create the stark contrast between Mary's humble beginnings and her luxurious lifestyle. Bauer was particularly interested in exploring the psychological motivations of his characters, and he encouraged his actors to deliver subtle, nuanced performances rather than the exaggerated acting common in many silent films of the era. The film's cinematography featured innovative techniques including unusual camera angles and lighting effects that emphasized the moral and emotional states of the characters.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Boris Zavelev employed innovative techniques that were advanced for 1914. Bauer utilized unusual camera angles, including high and low shots, to emphasize power dynamics between characters. The film featured sophisticated use of lighting to create mood and psychological atmosphere, particularly in contrasting the bright, luxurious world Victor inhabits with Mary with the dark, oppressive environment of the sweatshop. Deep focus compositions allowed multiple planes of action within single shots, creating visual depth and complexity. The film also made effective use of location shooting in Moscow, capturing the contrast between wealthy districts and working-class neighborhoods. Mirror shots and reflections were used to create psychological depth and suggest characters' internal states.

Innovations

The film demonstrated several technical innovations that were ahead of their time. Bauer's use of mobile camera movement, including tracking shots that follow characters through spaces, was particularly advanced for 1914. The film employed sophisticated editing techniques, including cross-cutting between parallel actions to build dramatic tension. The lighting design was notably complex, using natural light and artificial illumination to create mood and emphasize psychological states. The production design effectively contrasted different social environments through detailed set decoration and location choices. The film's pacing and narrative structure showed a sophisticated understanding of cinematic storytelling that would not become common in international cinema for several more years.

Music

As a silent film, 'Child of the Big City' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The specific musical scores used have not been preserved, but typical Russian cinema of this era employed a combination of classical music pieces and original compositions performed by piano or small orchestras. The music would have been synchronized with the on-screen action and emotional tone of scenes, with dramatic moments accompanied by intense musical passages and romantic scenes featuring softer melodies. Modern screenings of the film often feature newly composed scores or carefully selected classical music that reflects the film's Russian origins and dramatic themes.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, the dialogue was conveyed through intertitles. Key intertitles included: 'Mary dreamed of a life beyond the sweatshop', 'Victor's money seemed endless to Mary', 'When the money was gone, so was Mary's love', 'In the cold room, Victor still dreamed of Mary'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing Mary working in the oppressive sweatshop environment, using high-angle shots to emphasize her powerlessness

- The lavish party scene where Mary first experiences wealth, featuring elaborate costumes and sophisticated cinematography

- The confrontation scene where Victor suggests leaving the city, shot through mirrors to emphasize psychological tension

- The final scene showing Victor in his impoverished room, using stark lighting and composition to emphasize his complete ruin

Did You Know?

- This film was one of the earliest examples of Russian cinema exploring themes of social mobility and moral corruption in urban environments.

- Director Yevgeni Bauer was considered one of the most innovative filmmakers of his time, known for pioneering techniques like deep focus and complex camera movements.

- The film was released just months before World War I began, capturing the final days of Imperial Russian society.

- Yelena Smirnova, who played Mary, was one of the most popular actresses in Russian cinema during the 1910s.

- The film's negative portrayal of bourgeois decadence was considered somewhat controversial for its time.

- Bauer often used mirrors and reflections in his films to create psychological depth, a technique employed in this production.

- The original Russian title was 'Дитя большого города' (Ditya bol'shogo goroda).

- This was one of over 80 films Bauer directed before his premature death in 1918.

- The film's themes of social climbing and moral decay would become common in later Russian and Soviet cinema.

- Only fragments of many Bauer films survive today, but 'Child of the Big City' is relatively well-preserved.

What Critics Said

Contemporary Russian critics praised the film for its sophisticated storytelling and psychological depth. Reviews in Moscow newspapers highlighted Bauer's innovative direction and Smirnova's compelling performance. The film was noted for its realistic portrayal of urban life and its unflinching examination of moral corruption. Modern film historians consider 'Child of the Big City' one of Bauer's most important works, citing its technical innovations and narrative complexity. Critics today appreciate the film's ahead-of-its-time exploration of psychological motivation and social commentary. The film is frequently studied in film history courses as an example of the artistic achievements of pre-revolutionary Russian cinema.

What Audiences Thought

The film was popular with Russian audiences in 1914, particularly in urban centers like Moscow and St. Petersburg. Viewers were drawn to its dramatic storyline and the glamorous yet cautionary tale it presented. The film's themes of social aspiration and moral decay resonated with audiences experiencing rapid social change. Contemporary accounts suggest that the film generated considerable discussion about social mobility and the moral implications of wealth-seeking behavior. The film's success helped establish Yevgeni Bauer as one of the leading directors in Russian cinema and contributed to the growing popularity of domestic Russian productions over foreign imports.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Works of Fyodor Dostoevsky (themes of psychological torment and moral corruption)

- French literary realism

- Early Scandinavian psychological dramas

- Contemporary Russian literature examining social issues

This Film Influenced

- Later Russian films examining social mobility and moral corruption

- Soviet films of the 1920s that explored urban themes

- International films dealing with similar themes of social climbing and its consequences

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is partially preserved with some sequences missing or damaged. Prints exist in Russian film archives, particularly the Gosfilmofond collection, and some international archives. The film has been partially restored, though some scenes remain incomplete due to the deterioration of nitrate film stock. The surviving footage allows for a coherent understanding of the narrative, though approximately 15-20% of the original footage may be lost. The film has been digitized and is occasionally screened at film festivals and special retrospectives of early Russian cinema.