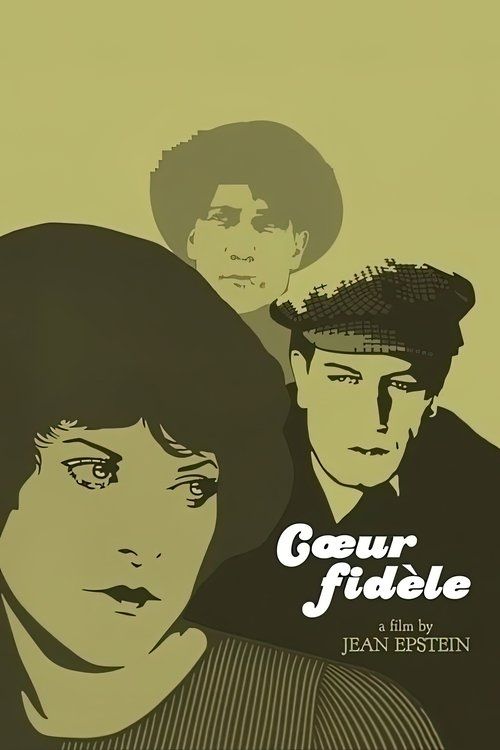

Cœur fidèle

Plot

Marie, a young orphan working as a waitress in a Marseille port tavern, is cruelly abused by her aunt and uncle who exploit her labor. She finds solace in her relationship with Jean, a humble dockworker who genuinely loves her, but her life is complicated by Petit Paul, a brutish sailor who obsessively pursues her. After Petit Paul's violent actions lead to tragedy and Marie's imprisonment, Jean remains devoted and patiently awaits her release. The film culminates in a tender reunion where Jean rescues Marie from her abusive family, and the two lovers finally escape together to begin a new life, embodying the triumph of pure love over corruption and violence.

About the Production

The film was shot on location in Marseille's old port district, providing authentic backdrop for the dockworker scenes. Epstein utilized natural lighting and real locations extensively, which was innovative for French cinema of the period. The production faced challenges filming in the working port, requiring coordination with actual dock operations and fishermen.

Historical Background

Cœur fidèle was produced during a pivotal period in French cinema history, when the industry was transitioning from the dominance of Pathé and Gaumont to more independent production companies. The early 1920s saw French cinema struggling to compete with American films, which dominated the market. This period also witnessed the emergence of the French avant-garde movement, with filmmakers like Epstein pushing the boundaries of cinematic language. The film reflects post-World War I French society's fascination with realism and the lives of working-class people. Marseille, as a major port city, represented both France's maritime heritage and its connection to international commerce. The film's themes of abuse and redemption resonated with a society still processing the trauma of war and seeking moral clarity in a rapidly changing world.

Why This Film Matters

Cœur fidèle represents a crucial bridge between traditional French melodrama and the cinematic avant-garde. Its innovative use of location shooting, natural lighting, and dynamic camera movements influenced subsequent French filmmakers and contributed to the development of poetic realism in the 1930s. The film is now recognized as a masterpiece of silent cinema, showcasing how conventional melodramatic material could be elevated through sophisticated visual techniques. Epstein's approach to editing and rhythm in this film prefigured later developments in film language, particularly in how he used montage to convey emotional states rather than merely advancing plot. The film's rediscovery in the 1970s contributed to a reevaluation of French silent cinema and helped establish Epstein's reputation as a pioneering auteur. Today, it's studied in film schools as an example of how artistic innovation can transform genre material.

Making Of

Jean Epstein, a former medical student turned filmmaker, brought a unique intellectual approach to this melodrama. He insisted on extensive location shooting in Marseille's Vieux-Port, which was unusual for French productions that typically relied on studio sets. The director worked closely with his cinematographer to develop innovative camera movements, including tracking shots that followed characters through the narrow streets of Marseille. Gina Manès, already an established star, reportedly immersed herself in the role by spending time with actual working-class women in Marseille. The production faced numerous challenges including weather delays during outdoor shooting and difficulties obtaining permits to film in the active port area. Epstein's insistence on authenticity extended to using real sailors and dockworkers as background performers, though this sometimes created scheduling conflicts when actual port operations took priority.

Visual Style

The cinematography, credited to Paul Guichard and Epstein himself, was revolutionary for its time. The film features extensive location photography in Marseille's old port, utilizing natural light to create authentic atmosphere. Epstein employed innovative camera movements including tracking shots that follow characters through narrow streets and dynamic angles during dramatic sequences. The film's visual style combines documentary-like realism with poetic expressionism, particularly in scenes where subjective camera work conveys Marie's emotional state. The use of actual maritime locations and working port facilities provided a gritty authenticity that was rare in French cinema of the period. The cinematography also features sophisticated compositions that use architectural elements to frame characters and reinforce themes of confinement and freedom.

Innovations

Cœur fidèle pioneered several technical innovations that would influence French cinema for decades. Epstein's use of location shooting in active working environments was groundbreaking, requiring portable equipment and innovative lighting solutions. The film features some of the earliest examples of handheld camera work in French narrative cinema, particularly in scenes following characters through Marseille's crowded streets. Epstein also experimented with variable speed cinematography, using slow motion for emotional moments and accelerated motion for sequences of violence or chaos. The film's editing technique, influenced by Soviet montage theory but adapted for emotional rather than ideological purposes, was innovative in its use of rhythmic cutting to convey psychological states. The production also developed new methods for shooting on water, using specially designed camera mounts to film scenes on boats and docks.

Music

As a silent film, Cœur fidèle would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The exact compositions used are not documented, but typical French cinema practice of the period would have involved either improvisation by a house organist or pianist, or specially compiled classical pieces. Modern restorations have been accompanied by newly commissioned scores, most notably a 1995 composition by French musician Jean-Louis Fournier that emphasizes the film's maritime setting through nautical themes. The 2002 Criterion Collection release featured a score by Timothy Brock that incorporated period-appropriate French popular music and classical pieces. Some contemporary screenings feature live musical accompaniment, with musicians drawing from both traditional French folk melodies and modern minimalist compositions to match the film's emotional rhythms.

Famous Quotes

"Mon cœur est fidèle, même quand tout le monde m'abandonne." (My heart is faithful, even when everyone abandons me.)

"Dans ce port de misère, j'ai trouvé le trésor de ton amour." (In this port of misery, I found the treasure of your love.)

"Chaque vague qui frappe le quai me rappelle que la vie est une lutte constante." (Every wave that hits the quay reminds me that life is a constant struggle.)

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence following Marie through the pre-dawn streets of Marseille as she heads to work, establishing both the urban environment and her daily struggle

- The dramatic confrontation on the docks where Petit Paul's jealousy explodes into violence, filmed with dynamic camera movements and rapid editing

- The prison visit scene where Jean's unwavering devotion is conveyed through subtle gestures and lighting

- The final escape sequence where Marie and Jean run through the narrow streets toward freedom, shot with handheld camera to create urgency and intimacy

- The tender reunion scene at the film's conclusion, where the lovers' embrace is framed against the rising sun over the port

Did You Know?

- Jean Epstein was only 24 years old when he directed this film, yet it's considered one of his masterworks

- The film was initially a commercial failure but was later rediscovered and championed by French cinema historians

- Gina Manès, who played Marie, was one of the most prominent actresses in French silent cinema

- The Marseille sequences were among the first examples of location shooting in French narrative cinema

- Epstein considered this film his most personal work, saying it represented his 'cinematic philosophy'

- The film's title translates to 'Faithful Heart' in English

- It was one of the first French films to be influenced by Soviet montage theory

- The original negative was thought lost for decades before being rediscovered in the 1970s

- Epstein used actual dockworkers as extras to ensure authenticity

- The film's pacing and visual style were revolutionary for French cinema of the early 1920s

What Critics Said

Contemporary French critics gave the film mixed reviews, with some praising its visual innovation while others found its melodramatic plot conventional. Le Petit Parisien criticized the film's 'excessive sentimentality' but acknowledged Epstein's 'remarkable visual sense.' Modern critics have been far more appreciative, with Cahiers du Cinéma calling it 'a revelation of cinematic poetry' and placing it among the essential works of French silent cinema. The British Film Institute's Sight & Sound magazine included it in their list of lost masterpieces before its rediscovery, and subsequent re-evaluation has established it as a crucial work in film history. Contemporary scholars particularly praise Epstein's innovative use of the camera and his ability to transcend melodramatic conventions through cinematic technique.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reception in 1923 was modest, as French cinema-goers at the time preferred more straightforward entertainment and found Epstein's artistic approach challenging. The film performed poorly in Paris but had slightly better reception in provincial theaters, particularly in Marseille where locals appreciated the authentic location shooting. Modern audiences, particularly at film festivals and cinematheque screenings, have responded much more positively, with many expressing surprise at the film's contemporary feel and technical sophistication. The restoration and re-release in the 1980s introduced the film to new audiences who appreciated its blend of emotional storytelling and visual innovation. Today, it's frequently programmed in silent film retrospectives and is considered accessible to modern viewers despite its age.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Soviet montage theory

- German Expressionism

- French literary realism

- D.W. Griffith's narrative techniques

This Film Influenced

- L'Atalante

- Port of Shadows

- The Crime of Monsieur Lange

- Le Quai des brumes

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was considered lost for several decades before a complete print was discovered in the Czechoslovakian film archives in the 1970s. A major restoration was undertaken by the Cinémathèque Française in the 1980s using this print and additional fragments found in other archives. The restored version premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 1985. Further digital restoration was completed in 2002 for the Criterion Collection release, which included extensive color tinting based on original distribution notes. The film is now preserved in several archives worldwide, including the Cinémathèque Française, the British Film Institute, and the Museum of Modern Art.