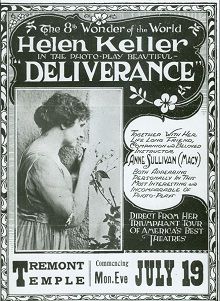

Deliverance

Plot

Deliverance (1919) is a silent biographical film that chronicles the remarkable life story of Helen Keller, from her early childhood isolation as a deaf and blind child to her breakthrough moment at the water pump with teacher Anne Sullivan, and ultimately to her graduation from Radcliffe College. The film portrays Keller's struggle to communicate with the world and the transformative impact of Sullivan's innovative teaching methods. Through reenactments and actual appearances by Keller and Sullivan, the film demonstrates how Keller overcame seemingly insurmountable obstacles to become an internationally recognized author, lecturer, and advocate for people with disabilities. The narrative culminates in Keller's academic achievements and her emergence as a symbol of human perseverance and the power of education.

About the Production

This was one of the earliest biographical films featuring the actual subjects portraying themselves. Helen Keller and Anne Sullivan Macy appeared in several scenes, making it a unique documentary-drama hybrid. The film was produced with the cooperation of the American Foundation for the Blind and was intended as both entertainment and educational tool to raise awareness about disability education. Production took place over several months in 1918-1919, with careful attention to historical accuracy in recreating key moments from Keller's life.

Historical Background

Deliverance was produced in the immediate aftermath of World War I, a time when American society was grappling with issues of rehabilitation and reintegration of wounded veterans. The film emerged during the Progressive Era's continued emphasis on social reform and education. In 1919, the concept of disability rights was virtually nonexistent, and people with disabilities were often institutionalized or hidden from public view. The film's production coincided with growing public interest in scientific approaches to education and rehabilitation. This was also a period when cinema was establishing itself as a powerful medium for both entertainment and social education. The film's release predated the establishment of the Academy Awards (1929) and came during the golden age of silent films, just before the industry would be revolutionized by sound technology.

Why This Film Matters

Deliverance holds immense cultural significance as one of the first films to portray disability with dignity and as a subject worthy of cinematic exploration. It challenged prevailing attitudes about the capabilities of people with disabilities at a time when such representation was virtually nonexistent. The film's use of the actual Helen Keller and Anne Sullivan Macy as performers created an unprecedented level of authenticity in biographical filmmaking. It helped establish Helen Keller as an international icon of perseverance and human potential, influencing public perception of disability for decades to come. The film also demonstrated cinema's potential as a tool for social advocacy and education, paving the way for future documentary and biographical works. Its existence challenged the film industry's tendency to avoid or misrepresent disabled individuals, though it would take many more decades before authentic disability representation became more common in Hollywood.

Making Of

The making of Deliverance was a groundbreaking endeavor in 1919, as it brought together the real Helen Keller and Anne Sullivan Macy to recreate pivotal moments from their lives. The production faced unique challenges in depicting the story of a deaf and blind protagonist in the silent film era. Director George Foster Platt worked closely with Keller and Sullivan to ensure authenticity, using intertitles to convey the internal thoughts and communication methods that couldn't be shown visually. The film was shot on location at places significant to Keller's life, including the actual water pump where her breakthrough occurred. Keller herself was deeply involved in the production, providing guidance on historical accuracy and even participating in the writing of some intertitles. The film's production was supported by various educational institutions and advocacy groups for the disabled, who saw it as an opportunity to advance public understanding and support for their causes.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Deliverance was typical of late silent era productions, utilizing stationary cameras and natural lighting where possible. Cinematographer Arthur Edeson employed careful composition to convey the isolation of Helen Keller's world before her education, often using shadows and framing techniques to suggest her sensory limitations. The water pump scene, the film's most famous sequence, was shot with particular attention to visual storytelling, using close-ups and intercutting to build emotional tension. The film made innovative use of actual location shooting rather than relying entirely on studio sets, which added to its documentary feel. The cinematography had to compensate for the lack of dialogue by emphasizing facial expressions and physical gestures, particularly in scenes with the young Helen Keller.

Innovations

Deliverance achieved several technical milestones for its time. It was one of the first films to successfully blend documentary footage with dramatic reenactment, creating a hybrid form that would later become common in biographical filmmaking. The film's use of actual locations rather than studio sets was innovative for 1919, adding authenticity to the production. The technical crew developed special techniques for filming scenes that needed to convey sensory deprivation, using lighting and camera angles to suggest Helen Keller's experience of the world. The film also pioneered early methods of educational film distribution, creating special versions for different audiences (general, educational, and international). The preservation of intertitles in both English and multiple other languages was technically advanced for the period.

Music

As a silent film, Deliverance would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its theatrical run. The original score was composed by William Frederick Peters and included popular classical pieces of the era alongside original compositions. The music was designed to enhance the emotional impact of key scenes, with softer, more melancholic themes during Helen's isolation and more uplifting melodies during her breakthrough moments. The score included adaptations of works by composers such as Chopin and Beethoven, which were chosen to reflect the film's themes of perseverance and triumph. Unfortunately, no complete recording of the original score survives, though some written musical cues and notations have been preserved in archival collections.

Famous Quotes

The only thing worse than being blind is having sight but no vision.

Alone we can do so little; together we can do so much.

The best and most beautiful things in the world cannot be seen or even touched - they must be felt with the heart.

Character cannot be developed in ease and quiet. Only through experience of trial and suffering can the soul be strengthened, ambition inspired, and success achieved.

Memorable Scenes

- The iconic water pump scene where Anne Sullivan spells 'w-a-t-e-r' into young Helen's hand, leading to her breakthrough understanding of language and communication

- Helen Keller's actual appearance at the end of the film, delivering a speech through finger spelling to demonstrate her achievements

- The reenactment of Helen's violent outbursts before Anne's arrival, showing the frustration of her isolated world

- The graduation ceremony scene showing Helen receiving her diploma from Radcliffe College

- The first meeting between Helen and Anne, depicting the initial struggle and resistance that eventually led to their lifelong bond

Did You Know?

- Helen Keller and Anne Sullivan Macy both appeared in the film, making it one of the earliest examples of biographical subjects portraying themselves on screen

- The film was produced by the Helen Keller Film Corporation, specifically created for this production

- Proceeds from the film were donated to support education for deaf and blind children

- This was one of the first films to feature disabled performers in leading roles

- The film included actual footage of Keller's graduation from Radcliffe College in 1904

- George Foster Platt was a relatively unknown director who specialized in educational films

- The film's title 'Deliverance' refers to Keller's deliverance from isolation through education

- Ardita Mellinino, who played the young Helen Keller, was a child actress specifically chosen for her ability to convey emotion without dialogue

- The film was screened at the White House for President Woodrow Wilson in 1919

- Only one complete print of the film is known to exist today, preserved at the Library of Congress

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception to Deliverance was largely positive, with reviewers praising its inspirational message and the novelty of featuring the real Helen Keller. The New York Times noted the film's 'profound emotional impact' and called it 'a testament to human endurance.' Variety praised its educational value while acknowledging its limited commercial appeal. Modern critics and film historians recognize Deliverance as an important early example of disability representation in cinema, though some critique it for occasionally veering into sentimentality typical of the period. The film is now studied in film history courses for its pioneering approach to biographical storytelling and its historical significance as an early disability-focused narrative.

What Audiences Thought

Contemporary audience reception to Deliverance was mixed in terms of commercial success but generally positive in terms of emotional impact. Many viewers reported being deeply moved by the story, particularly scenes featuring the actual Helen Keller. The film found its most enthusiastic audiences among educational institutions, advocacy groups, and religious organizations, who organized special screenings. General audiences, while impressed by the story, found the film's serious tone and educational focus less entertaining compared to typical Hollywood fare of the era. The film's limited release and specialized nature meant it never achieved wide commercial success, but it did reach and inspire many viewers through special screenings and educational distribution.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Miracle Worker (later play and film)

- Biographical films of the silent era

- Educational documentary movement

- Progressive Era social reform films

This Film Influenced

- The Miracle Worker (1962)

- The Story of Helen Keller (1954 TV)

- Monday After the Miracle (1998 TV)

- Various educational films about disability

- Biographical films featuring real subjects

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Deliverance is partially preserved with one complete 35mm print held at the Library of Congress. The film was considered lost for decades before being rediscovered in the 1960s. The surviving print shows some deterioration typical of films from this era but remains largely intact. The Library of Congress has undertaken preservation efforts to ensure the film's survival for future generations. Some scenes and intertitles are missing or damaged, but the core narrative is preserved. The film has been digitized and is available for scholarly research and limited public screenings.