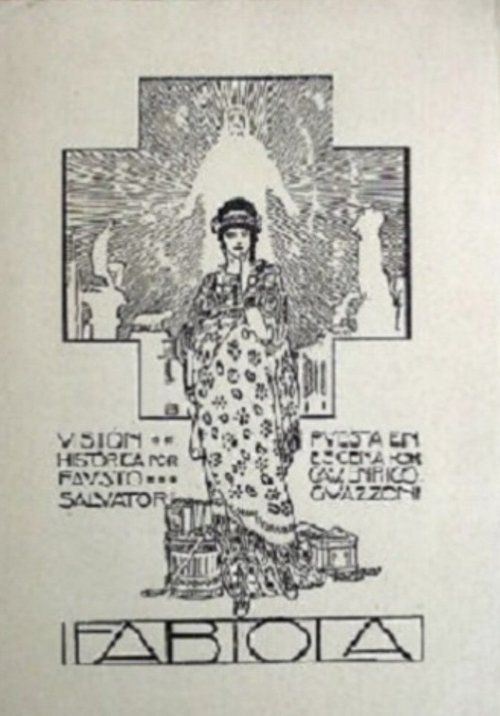

Fabiola

Plot

Fabiola (1918) tells the story of a young Roman noblewoman who converts to Christianity during the reign of Emperor Diocletian. After witnessing the courage and faith of Christian martyrs, Fabiola abandons her pagan lifestyle and embraces the new religion, despite the deadly persecution. The film follows her journey as she navigates the dangerous underground Christian community, hiding in catacombs and secret meeting places while Roman authorities hunt down believers. Fabiola's faith is tested through various trials including the martyrdom of her friends and loved ones, yet she remains steadfast in her devotion. The narrative culminates in a dramatic confrontation between the emerging Christian movement and the established Roman power structure, showcasing the transformation of Christianity from a persecuted sect to a force challenging the empire itself.

About the Production

Directed by Enrico Guazzoni, one of the pioneers of Italian historical epics, the film was produced during the final years of World War I, which likely impacted its production resources and distribution. The film featured elaborate sets designed to recreate ancient Rome and the Christian catacombs, typical of Guazzoni's attention to historical detail. The production utilized the large studio facilities of Cines, one of Italy's major film companies of the silent era.

Historical Background

Fabiola was produced in 1918, during the final year of World War I, a time of immense social and political upheaval across Europe. The film emerged from the golden age of Italian cinema (1914-1920), when Italian historical epics dominated international markets with their spectacular productions. This period saw Italian filmmakers competing with Hollywood by creating increasingly elaborate historical and mythological films. The focus on early Christian themes reflected both the source material's popularity and the broader cultural interest in spiritual questions during a time of unprecedented global conflict. The film's depiction of religious persecution and martyrdom resonated with audiences experiencing the traumas of war. Additionally, 1918 saw the Spanish flu pandemic sweeping across Europe, adding another layer of crisis to the film's release context. The Italian film industry, while still producing ambitious works, was beginning to feel the economic pressures that would eventually lead to its decline in the 1920s as Hollywood rose to dominance.

Why This Film Matters

Fabiola represents an important example of the Italian historical epic tradition that helped establish many conventions of the cinematic spectacle genre. The film contributed to the popularization of early Christian narratives in cinema, paving the way for later biblical and religious epics. As part of Enrico Guazzoni's body of work, it demonstrates the evolution of Italian cinema from general historical subjects to specifically religious themes, reflecting the cultural importance of Catholicism in Italian society. The film's production during World War I makes it a testament to the resilience of European cinema during periods of crisis. Its adaptation of a popular 19th-century Catholic novel shows how cinema became a medium for bringing beloved literary works to new audiences. The film also exemplifies the role of Italian cinema in establishing visual and narrative techniques for historical storytelling that would influence filmmakers worldwide, particularly in the epic genre.

Making Of

The production of Fabiola took place during a challenging period for European cinema, with World War I affecting both resources and international distribution. Director Enrico Guazzoni, already established as a master of the historical epic genre, brought his expertise in creating spectacular Roman settings to this Christian-themed narrative. The film required elaborate construction of catacomb sets and Roman streets, typical of the ambitious scale of Italian productions of this era. The casting of Giula Cassini-Rizzotto as Fabiola represented the practice of using established theater actors for leading roles in early Italian cinema. The film's focus on Christian martyrdom and persecution reflected both the source material's religious themes and the contemporary interest in spiritual subjects during the wartime period. Production likely faced challenges common to the era, including the limitations of early cinematic technology for creating dramatic spectacle and the coordination of large crowd scenes typical of historical epics.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Fabiola would have reflected the practices of Italian historical epics of the late 1910s, characterized by grand, sweeping compositions designed to showcase elaborate sets and large crowd scenes. The film likely employed static camera positions typical of the era, with careful framing to capture the architectural details of Roman settings and catacomb interiors. The visual style would have emphasized the contrast between the opulence of pagan Rome and the humble secrecy of Christian gatherings. Lighting techniques would have been rudimentary by modern standards but sophisticated for the time, using natural light and studio lighting to create dramatic effects, particularly in scenes depicting martyrdom or divine intervention. The black and white photography would have relied on contrast and composition to convey emotional tone and narrative significance, with careful attention to visual storytelling techniques essential for silent cinema.

Innovations

Fabiola would have showcased several technical achievements typical of Italian historical epics of its era. The film's production likely involved the construction of massive, detailed sets representing ancient Roman architecture and Christian catacombs, demonstrating advanced set design and construction techniques for the period. The coordination of large crowd scenes with hundreds or thousands of extras required sophisticated logistical planning and camera choreography. The film may have utilized early special effects techniques such as matte paintings or multiple exposures to create dramatic visions or supernatural elements. The cinematography, while technically straightforward by modern standards, would have required considerable skill in lighting and composition to capture the grand scale of the productions. The film's length and narrative complexity represented technical challenges in editing and continuity that were still being refined during this period of cinema's development.

Music

As a silent film, Fabiola would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its theatrical exhibition. The score would likely have been compiled from existing classical pieces or composed specifically for the film by a theater's musical director. Religious themes would have been underscored with solemn, devotional music, while scenes of Roman spectacle might have featured grand, dramatic compositions. The musical accompaniment would have been crucial for conveying emotional tone and narrative emphasis in the absence of dialogue. Theaters showing the film might have used organs, pianos, or small orchestras depending on their size and resources. The musical style would have reflected late Romantic and early 20th-century sensibilities, with leitmotifs possibly assigned to main characters or themes. The soundtrack would have been an integral part of the audience's experience, though specific details about Fabiola's musical accompaniment have not survived.

Famous Quotes

Quotes from silent films are not typically preserved in written form, as the intertitles contained narrative exposition rather than memorable dialogue

Memorable Scenes

- The catacomb sequences depicting secret Christian worship services, likely featuring dramatic lighting and large gatherings of believers hiding from Roman authorities

- Scenes of Christian martyrdom in the Roman arena, a common spectacle in films of this era

- Fabiola's conversion scene, showing her transformation from pagan noblewoman to devout Christian

- The climactic confrontation between Christian and Roman forces, showcasing the film's epic scale

Did You Know?

- Based on the 1854 novel 'Fabiola, or The Church of the Catacombs' by Cardinal Nicholas Wiseman, which was one of the most popular Catholic novels of the 19th century

- Director Enrico Guazzoni was renowned for his historical spectacles, having previously directed 'Quo Vadis' (1913), one of the first feature-length epics in cinema history

- The film was part of the golden age of Italian silent cinema, when Italian films dominated international markets with their lavish historical productions

- This was one of multiple adaptations of the Fabiola story, with later versions made in 1949 and 1960

- The film's production occurred during World War I, a period when many European film industries struggled with resource shortages and distribution challenges

- Italian historical epics of this era were known for their massive sets, thousands of extras, and attention to historical detail, setting standards for epic filmmaking

- The Cines studio, where this was filmed, was one of Italy's most important early film production companies before being damaged during World War II

- The film represented a shift in Guazzoni's work from earlier Roman Empire settings to focus specifically on early Christian history

- Silent films about early Christianity were particularly popular in the 1910s as they could be marketed to both religious and general audiences

- The preservation status of many Italian films from this period is uncertain due to the nitrate film stock's tendency to deteriorate and wartime destruction

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of Fabiola is difficult to reconstruct due to the scarcity of surviving reviews from the 1918 period. However, films by Enrico Guazzoni were generally well-received by critics of the era for their spectacular visuals and attention to historical detail. The film's religious theme likely garnered positive attention from Catholic publications and reviewers who appreciated faithful adaptations of popular religious novels. Critics would have evaluated the film based on the standards of silent cinema, particularly its visual storytelling, set design, and the performances of its leading actors. The film's release during wartime may have influenced critical assessments, with some reviewers potentially viewing its themes of faith and perseverance as particularly relevant to the times. Modern critical assessment is limited by the film's apparent lost or incomplete status, preventing contemporary scholars from fully evaluating its artistic merits and historical importance.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception of Fabiola in 1918 would have been influenced by several factors including its religious subject matter, spectacular production values, and the wartime context. The adaptation of Cardinal Wiseman's popular novel likely attracted readers familiar with the source material, while the spectacle of ancient Rome would have appealed to general audiences seeking entertainment and escapism during the difficult war years. Italian audiences of this period showed particular enthusiasm for historical epics that celebrated their cultural heritage, and films with Christian themes often resonated strongly in the predominantly Catholic country. The film's depiction of Christian persecution and martyrdom may have had special meaning for audiences experiencing the hardships of war. International reception would have been affected by wartime distribution challenges, though Italian films of this era were popular in many markets before the war disrupted global film trade.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Cardinal Nicholas Wiseman's novel 'Fabiola' (1854)

- Italian historical epic tradition

- Earlier biblical films like 'From the Manger to the Cross' (1912)

- Guazzoni's own previous epics like 'Quo Vadis' (1913)

- 19th-century Catholic literature

- Roman history and archaeology

This Film Influenced

- Later adaptations of Fabiola (1949, 1960)

- Biblical epics of the 1950s like 'Quo Vadis' (1951)

- The Robe (1953)

- Ben-Hur (1959)

- Other films about early Christian persecution

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of Fabiola (1918) is uncertain, and the film may be partially or completely lost. Many Italian silent films from this period have not survived due to the unstable nature of nitrate film stock, wartime destruction, and inadequate preservation efforts in the early 20th century. Some sources suggest fragments or incomplete versions may exist in film archives, but a complete, restored version appears to be unavailable for public viewing. The loss of this film represents a significant gap in the documentation of Enrico Guazzoni's work and the Italian historical epic tradition.