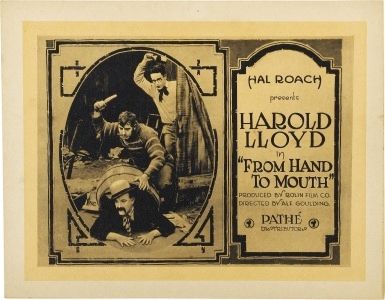

From Hand to Mouth

"A Comedy of Hunger and Heroes"

Plot

In this Harold Lloyd comedy, our hero plays a penniless young man struggling to find his next meal when he encounters a young waif and her loyal dog who are in equally dire straits. Meanwhile, across town, a corrupt attorney is conspiring with a criminal gang to swindle a wealthy young heiress out of her fortune through fraudulent legal means. When the heiress leaves the lawyer's office, she witnesses the young man and the waif being harassed by authorities and intervenes to help them. Later, when the heiress finds herself in genuine danger from the criminals who are now targeting her directly, Lloyd's character unexpectedly gets the chance to return her kindness and save her from their sinister plot, leading to a thrilling climax filled with classic Harold Lloyd physical comedy and daring stunts.

About the Production

This film was produced during Harold Lloyd's most prolific period of short comedies, before he transitioned to feature-length films. The production utilized real locations in Los Angeles rather than studio sets for many exterior scenes, giving it an authentic urban feel. The film showcases Lloyd's signature blend of physical comedy with everyday situations that audiences could relate to, particularly the post-war economic struggles many Americans were facing.

Historical Background

'From Hand to Mouth' was produced in 1919, a pivotal year in American history as the nation transitioned from World War I to the Roaring Twenties. The film reflected the economic uncertainty many Americans faced during this period, with returning soldiers competing for jobs and inflation affecting daily life. The Spanish Flu pandemic was still affecting the country, influencing both film production and theater attendance. This was also during the height of the silent film era, before Hollywood established itself as the global center of cinema production. The film industry was undergoing significant changes, with stars like Harold Lloyd, Charlie Chaplin, and Buster Keaton becoming cultural icons and powerful independent producers who controlled their own work.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents an important example of Harold Lloyd's development as a comedy star and his unique contribution to silent cinema. Unlike Chaplin's 'Little Tramp' or Keaton's 'Stone Face,' Lloyd created an optimistic, ambitious 'everyman' character that audiences could both laugh at and aspire to be like. The film's themes of economic struggle and eventual triumph resonated strongly with post-WWI American audiences facing their own financial challenges. The combination of physical comedy with relatable social situations helped establish a template for American screen comedy that would influence generations of filmmakers. The film also demonstrates the early development of the crime comedy genre, blending suspenseful elements with humor in a way that would become increasingly popular in subsequent decades.

Making Of

The filming of 'From Hand to Mouth' took place during a transitional period in Harold Lloyd's career, as he was developing his iconic 'Glasses Character' that would make him famous. Director Alfred J. Goulding, an Australian filmmaker, had been working closely with Lloyd since 1918 and helped refine his comedy style away from mere slapstick toward more character-driven humor. The production faced challenges typical of the era, including limited lighting equipment for night scenes and the need to shoot quickly due to the expensive film stock. Mildred Davis and Harold Lloyd developed their real-life romance during this period of working together on multiple films. The child actress Peggy Cartwright reportedly had difficulty with some scenes requiring her to appear distressed, leading the crew to use various techniques to elicit genuine emotions from the young performer.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Walter Lundin utilized the natural lighting techniques common in 1919, with careful attention to exterior scenes that captured the urban landscape of Los Angeles. The film employed innovative camera movements for chase sequences, using tracking shots that were relatively advanced for the period. The visual composition emphasized Lloyd's physical comedy through strategic framing that highlighted his athletic movements and expressive face. Night scenes were particularly challenging given the technical limitations of the era, requiring creative solutions including the use of multiple reflectors and available light sources. The cinematography successfully balanced the comedic elements with moments of genuine suspense during the crime subplot, using lighting and camera angles to create appropriate mood shifts.

Innovations

While not groundbreaking in technical innovation, 'From Hand to Mouth' demonstrated solid filmmaking craftsmanship typical of quality productions from 1919. The film employed effective editing techniques to build suspense during the crime sequences and maximize comedic timing during physical comedy scenes. The production utilized location shooting effectively, creating a realistic urban environment that enhanced the story's credibility. The film's stunts, while not as elaborate as some of Lloyd's later famous sequences, still required careful planning and execution to achieve both comedic effect and safety for the performers. The preservation of multiple shots in sequence for chase scenes showed growing sophistication in film continuity and editing techniques that were still developing during this period.

Music

As a silent film, 'From Hand to Mouth' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. Theaters typically employed pianists or small orchestras who would select appropriate music from cue sheets provided by the studio or improvise based on the action on screen. The score likely included popular songs of 1919, classical pieces, and original compositions tailored to the film's various moods - from light-hearted comedy music during humorous scenes to more dramatic, suspenseful pieces during the crime elements. Modern restorations of the film have been scored by contemporary silent film composers who attempt to recreate the musical experience of the original era while adding modern sensibilities.

Famous Quotes

(Silent films had no spoken dialogue, but intertitles included: 'When hunger gnaws at your stomach and your pockets are empty, life seems pretty bleak.'

'Sometimes the smallest kindness can change your whole life.'

'In a world of wolves, even the sheep must learn to fight.'

'Poverty may be temporary, but honor is forever.'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where Harold Lloyd's character desperately tries to find food, using increasingly inventive but failed methods to obtain a meal

- The chance encounter between Lloyd and the heiress when she rescues him and the young waif from police harassment

- The climactic chase sequence through the streets of Los Angeles as Lloyd pursues the criminals to save the heiress

- The final confrontation scene where Lloyd uses his wits rather than strength to overcome the villains and save the day

Did You Know?

- This was one of the early films where Harold Lloyd worked with Mildred Davis, who would later become his wife in real life and his frequent leading lady

- The film was released during the Spanish Flu pandemic, which affected theater attendance nationwide

- Director Alfred J. Goulding directed numerous Harold Lloyd shorts during this period, helping establish Lloyd's signature comedy style

- The 'waif' character played by Peggy Cartwright was one of the first child stars of the silent era

- The dog in the film was not professionally trained but was Harold Lloyd's own pet, adding authenticity to their scenes together

- This film was part of Lloyd's transition from more slapstick comedy toward his more sophisticated 'everyman' character

- The criminal gang subplot was unusual for Lloyd's films of this period, which typically focused more on romantic and workplace comedies

- The film's title refers to the common phrase 'from hand to mouth,' meaning barely having enough to survive from day to day

- Only one print of this film was known to survive for many decades in a private collection before being restored

- The exterior street scenes provide valuable documentation of Los Angeles streetscapes from 1919

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews in 1919 praised the film for its clever blend of comedy and suspense, with trade publications noting Harold Lloyd's growing sophistication as a performer. The Motion Picture News particularly highlighted the film's 'genuinely thrilling sequences' balanced with 'laugh-provoking situations.' Modern critics have come to appreciate the film as a significant example of Lloyd's transitional work, showing his evolution from pure slapstick toward more nuanced comedy. Film historians have noted how the movie captures the social atmosphere of post-war America while providing entertainment that transcended its time period. The restoration of the film in recent years has allowed new generations of critics to reassess its place in Lloyd's filmography and silent comedy history.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1919 responded enthusiastically to 'From Hand to Mouth,' finding both humor and relatability in its depiction of economic struggle and eventual triumph. The film performed well in theaters despite the ongoing Spanish Flu pandemic that limited public gatherings. Harold Lloyd's growing popularity as a comedy star helped drive attendance, as did the appealing presence of Mildred Davis as his leading lady. Contemporary audience letters preserved in film archives show particular appreciation for the film's exciting climax and the chemistry between Lloyd and his young co-stars. The combination of comedy, romance, and suspense elements appealed to broad audiences, helping establish Lloyd as one of the top box office draws of the silent era alongside Chaplin and Keaton.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Earlier Charlie Chaplin shorts featuring similar 'down-and-out' characters

- Mack Sennett's Keystone comedies with their blend of romance and crime elements

- Contemporary newspaper stories about post-war economic struggles

- Popular dime novel plots featuring heroes saving heiresses from danger

This Film Influenced

- Later Harold Lloyd features that expanded on the 'everyman' character

- Frank Capra films featuring ordinary heroes helping wealthy heroines

- Subsequent crime comedies that blended suspense with humor

- Modern romantic comedies with 'opposites attract' themes

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was believed lost for decades but a single 35mm nitrate print was discovered in a private collection in the 1970s. This print was subsequently preserved by the Library of Congress and has undergone digital restoration. While not complete, the restored version contains the majority of the original film with some deterioration in certain scenes due to the nitrate decomposition. The preservation status is considered good for a film of its era, allowing modern audiences to experience this important Harold Lloyd comedy.