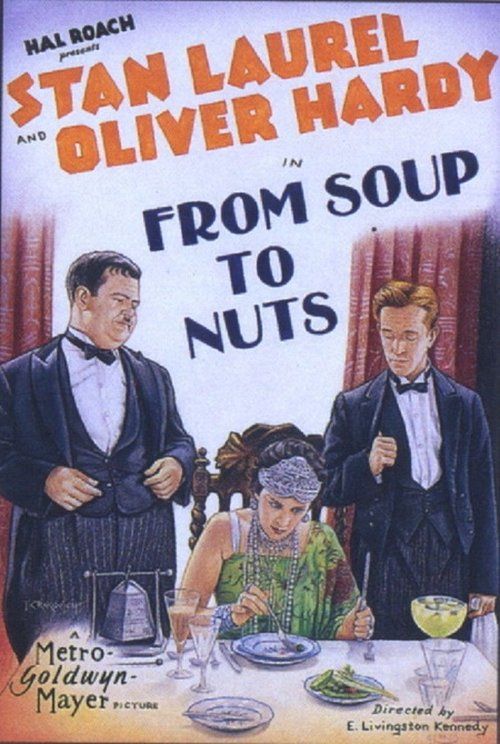

From Soup to Nuts

"The Greatest Comedy Team in the World in Their Latest Laugh Riot!"

Plot

Stan and Ollie are hired as waiters for an elegant dinner party hosted by the wealthy Mrs. Culpepper, despite having absolutely no experience in the service industry. Their incompetence quickly becomes apparent as they struggle with basic tasks like carrying trays, serving soup, and navigating the formal dining room. The chaos escalates when they accidentally spill soup on guests, break dishes, and create a series of escalating disasters that turn the sophisticated evening into complete pandemonium. Their attempts to rectify each mistake only lead to greater catastrophes, culminating in a food fight that destroys the entire dinner party. The film ends with the duo being unceremoniously fired, leaving behind a scene of utter devastation.

About the Production

This was one of the early Laurel and Hardy shorts where their classic comedic partnership was being refined. The film was shot during the transition period from silent films to talkies, though it was released as a silent comedy. Edgar Kennedy, who directed this film, was a regular supporting actor in Laurel and Hardy films and was part of their stock company of character actors. The dinner party set was constructed specifically for this production and was designed to be easily destroyable for the chaotic finale.

Historical Background

1928 was a year of tremendous transition in Hollywood, with the film industry grappling with the revolutionary impact of sound technology. While 'The Jazz Singer' had already demonstrated the commercial viability of talkies in 1927, many studios, including Hal Roach Productions, continued producing silent films well into 1928. This film represents the pinnacle of silent physical comedy, created just as the art form was about to be transformed forever. The late 1920s also saw the rise of the comedy duo format, with Laurel and Hardy emerging as one of the most popular teams alongside contemporaries like Wheeler and Woolsey. The film's focus on class dynamics, with working-class comedies disrupting high society gatherings, reflected the social tensions of the Roaring Twenties, a period marked by both unprecedented prosperity and growing inequality.

Why This Film Matters

'From Soup to Nuts' represents a crucial moment in the development of American comedy, showcasing the refined Laurel and Hardy formula that would influence generations of comedians. The film's exploration of incompetence in professional settings became a template for countless workplace comedies that followed. The dinner party as a setting for comedic chaos has been endlessly referenced in popular culture, from television sitcoms to modern films. This short helped establish the physical comedy language that would become synonymous with Laurel and Hardy's work, influencing everything from The Three Stooges to modern comedy duos. The film's success demonstrated the international appeal of visual comedy, transcending language barriers and helping establish American comedy's global dominance in the early sound era.

Making Of

The production of 'From Soup to Nuts' took place during a pivotal time at Hal Roach Studios when the studio was experimenting with different formats for comedy shorts. Director Edgar Kennedy, typically known for his slow-burn comedic performances as an actor, brought a unique perspective to the pacing of the physical comedy. The famous soup-spilling sequence required multiple takes to perfect the timing, with Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy having to rehearse the choreography extensively. Anita Garvin, playing the society hostess, had to maintain her composure through multiple takes of the chaotic scenes, which proved challenging given the physical nature of the comedy. The set design was crucial to the film's success, with the dining room constructed to allow maximum destruction while maintaining the illusion of an elegant setting. The film's climax, featuring an all-out food fight, was one of the most elaborate sequences in a Laurel and Hardy short up to that point.

Visual Style

The cinematography by George Stevens employs wide shots to capture the full scope of the dining room chaos, allowing audiences to appreciate the carefully choreographed destruction. The camera work is notably steady during the most chaotic sequences, providing a clear view of the physical comedy without the shaky camera work that would later become common in action scenes. The lighting design creates the illusion of an elegant, well-lit dining room while ensuring that all the comedic action remains visible. The film uses medium close-ups effectively to capture Laurel and Hardy's reactions to the disasters they create, a technique that became a hallmark of their films. The cinematography successfully balances the need to show both the broad physical comedy and the subtle facial expressions that made the duo so beloved.

Innovations

While 'From Soup to Nuts' doesn't feature groundbreaking technical innovations, it demonstrates the mastery of silent film techniques at their peak. The film's use of continuity editing during the chaotic sequences maintains clarity despite the complexity of the action. The practical effects, particularly the destruction of the dinner set, were executed with precision and timing that would be difficult to replicate in modern CGI-heavy productions. The film showcases the sophisticated understanding of comedic timing that had developed in silent cinema, with editing rhythms perfectly matched to the physical comedy. The sound stage construction allowed for multiple camera angles during the dinner party sequence, a technical achievement that enhanced the visual storytelling of the chaos.

Music

As a silent film, 'From Soup to Nuts' was originally accompanied by live musical performances in theaters. The typical score would have included popular songs of the era, classical pieces, and specially composed mood music to enhance the comedy. The Hal Roach Studios often provided suggested musical cues with their films, recommending specific pieces for different scenes. For the dinner party sequences, elegant classical music would have been used to contrast with the chaos, while more upbeat, frantic music would accompany the physical comedy. Modern releases of the film typically feature newly composed scores or compilations of period-appropriate music, with some versions including sound effects to enhance the impact of the physical gags.

Famous Quotes

(Stan, after spilling soup) 'I'm sorry, madam. It slipped.'

(Ollie, to Stan) 'Why don't you use your head for something besides a hat rack?'

(Mrs. Culpepper) 'You two are the most incompetent waiters I have ever seen!'

Memorable Scenes

- The escalating disaster sequence where Stan and Ollie attempt to serve soup, resulting in a chain reaction of spills, broken dishes, and guest complaints that culminates in an all-out food fight destroying the elegant dinner party.

Did You Know?

- This was one of the few Laurel and Hardy films directed by Edgar Kennedy, who usually appeared as an actor in their films rather than directing them.

- The film features the debut of Anita Garvin as a recurring character in Laurel and Hardy films, appearing as Mrs. Culpepper.

- The soup-spilling scene became one of the most referenced gags in comedy history and was later homaged in numerous films and television shows.

- This was released during the height of the silent film era, just before the transition to sound films would revolutionize Hollywood.

- The original working title was 'The Waiters' before being changed to the more whimsical 'From Soup to Nuts'.

- The film was shot in just three days, typical of the rapid production schedule of Hal Roach comedy shorts.

- The dinner party scene required 75 extras to play the guests, all of whom had to be carefully choreographed for the chaotic finale.

- The film was one of Laurel and Hardy's most popular shorts of 1928 and helped cement their status as a major comedy duo.

- The broken dishes in the film were real porcelain, not props, making the cleanup after filming particularly challenging.

- This short was included in the original Laurel and Hardy film package that was distributed internationally, helping establish their global popularity.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised 'From Soup to Nuts' for its expert timing and escalating chaos, with Variety noting that 'Laurel and Hardy have perfected their unique brand of mayhem to a fine art.' The Motion Picture News called it 'one of the funniest shorts of the year' and specifically highlighted the dinner party sequence as 'a masterpiece of comedic destruction.' Modern critics and film historians view the film as an essential example of silent comedy at its peak, with Leonard Maltin describing it as 'a perfect showcase for the duo's chemistry and physical comedy skills.' The film is frequently cited in academic studies of silent comedy as an example of how Laurel and Hardy transformed slapstick from mere physical gags into character-driven comedy with emotional depth.

What Audiences Thought

The film was enormously popular with audiences in 1928, playing to packed houses in theaters across America and internationally. Audience reaction reports from the period indicate that the food fight sequence generated some of the biggest laughs of any comedy short that year. The film's success led to increased demand for Laurel and Hardy films, resulting in higher budgets and more elaborate productions for their subsequent shorts. In later years, the film became a staple of revival theaters and television retrospectives of classic comedy, introducing new generations to the duo's work. Modern audiences continue to respond enthusiastically to the film's timeless humor, with the dinner party sequence remaining one of the most shared and referenced moments in Laurel and Hardy's filmography.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Earlier comedy shorts by Charlie Chaplin

- Buster Keaton's engineering of physical comedy

- Harold Lloyd's escalation gags

- Mack Sennett's slapstick tradition

- Vaudeville comedy routines

This Film Influenced

- The Music Box (1932)

- Sons of the Desert (1933)

- A Night at the Opera (1935)

- The Party (1968)

- Dinner for Schmucks (2010)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in the Library of Congress collection and has been restored by the UCLA Film and Television Archive. Multiple high-quality versions exist, including those released by The Criterion Collection and Kino Lorber. The film has survived in excellent condition compared to many silent shorts of the era, with complete reels and minimal deterioration. Digital restorations have been completed, ensuring the film's preservation for future generations.