God's Little Acre

"The dirtiest book in America is now the most daring motion picture of the year!"

Plot

In Depression-era rural Georgia, Ty Ty Walden is a cotton farmer obsessed with finding gold he believes was buried on his land by his grandfather. His relentless digging has turned his farm into a crater-filled wasteland while his family struggles with poverty and hunger. His daughter-in-law Griselda engages in an affair with hired hand Dave Dawson, while his son Pluto remains unemployed and turns to alcohol. As Ty Ty's obsession intensifies and family secrets unravel, the Walden family's dysfunction threatens to completely destroy them, forcing a confrontation between their dreams of wealth and the harsh reality of their existence.

About the Production

The film faced significant censorship challenges due to its sexual content and was initially denied a Production Code seal. Director Anthony Mann had to make numerous cuts to appease censors, though the film was still considered quite daring for its time. The production used artificial cotton fields since filming in Georgia was deemed too expensive. The film was shot in CinemaScope, a relatively new widescreen process at the time.

Historical Background

God's Little Acre was produced during a pivotal moment in American cinema history, just as the restrictive Hays Code was beginning to lose its grip on Hollywood. The late 1950s saw increasing pressure on the film industry to address more adult themes and reflect changing social mores. The film's release coincided with the growing civil rights movement, which was bringing increased attention to the conditions of rural Southern communities. The Great Depression setting resonated with audiences who had lived through that era or heard stories from their parents. Hollywood was also competing with television by producing more daring content that couldn't be shown on the small screen. The film's frank treatment of sexuality and poverty reflected a broader cultural shift toward greater openness in American society, setting the stage for the more permissive filmmaking of the 1960s.

Why This Film Matters

God's Little Acre holds an important place in cinema history as one of the films that helped break down the censorship barriers of the Hays Code era. Its relatively frank depiction of sexuality and rural poverty paved the way for more realistic portrayals of American life in subsequent decades. The film was among the first major studio productions to suggest sexual relationships and infidelity without explicitly showing them, using implication and subtext to convey adult themes. Its commercial success demonstrated that audiences were ready for more mature content, encouraging other studios to take similar risks. The film also contributed to the popular image of the rural South in American cinema, influencing how poverty and Southern culture would be portrayed in later films. Additionally, it marked an important transition in Tina Louise's career and helped establish Jack Lord as a leading man before his television success.

Making Of

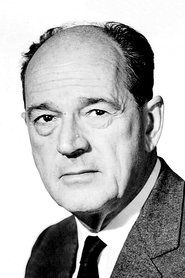

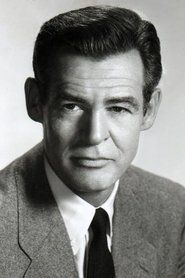

The production of God's Little Acre was marked by significant controversy and censorship battles. Director Anthony Mann, known for his work in westerns and noir, took on the challenging adaptation of Erskine Caldwell's controversial novel. The casting process was extensive, with Robert Ryan eventually securing the lead role after several other actors were considered. Tina Louise, a Broadway performer, was discovered for her film debut after Mann saw her in a stage production. The film's sexual content was groundbreaking for its time, leading to lengthy negotiations with the Production Code Administration. Multiple scenes had to be reshot or edited to secure approval, including the famous bathtub scene with Tina Louise, which was considered highly provocative for 1958. The production design team created an authentic Southern farm environment on California soundstages and location sets, using imported cotton plants and period-appropriate farm equipment. The film's controversial nature created significant buzz in Hollywood, with many industry insiders watching to see how audiences would respond to such adult themes.

Visual Style

The film's cinematography, handled by Ernest Haller, utilized the CinemaScope format to create sweeping vistas of the rural Georgia landscape, even though it was filmed in California. The wide-screen format emphasized both the isolation of the Walden family and the vastness of their neglected farm. Haller employed natural lighting techniques to create an authentic, gritty feel that reflected the harsh reality of Depression-era rural life. The camera work often used low angles to emphasize the physical toll of the characters' constant digging, while close-ups captured the emotional intensity of the family conflicts. The visual style contrasted the romanticized notion of Southern farm life with the harsh reality of poverty and obsession, using dusty, earthy color palettes to reinforce the film's themes of dirt and buried treasure.

Innovations

God's Little Acre utilized CinemaScope technology to create its widescreen presentation, which was relatively new in 1958 and allowed for more expansive framing of the rural settings. The film's production design team created innovative techniques for simulating Georgia farm environments on California locations, including the extensive use of artificial cotton plants and period-appropriate farming equipment. The sound recording techniques used for the film were advanced for their time, particularly in capturing outdoor dialogue scenes with minimal background noise. The makeup and costume departments achieved notable authenticity in creating Depression-era rural appearances, with careful attention to the wear and tear of clothing appropriate for impoverished farming families.

Music

The musical score was composed by Leonard Rosenman, who created a distinctive blend of folk-inspired melodies and dramatic orchestral passages that reflected the film's Southern setting and emotional intensity. Rosenman incorporated elements of traditional American folk music, using banjo and guitar motifs to establish the rural Georgia atmosphere while maintaining a contemporary cinematic sound. The score effectively underscored the film's dramatic moments without overwhelming the performances, and its use of leitmotifs helped distinguish between the various family members' emotional states. The music was particularly effective in scenes of tension and revelation, with Rosenman's dissonant harmonies reflecting the family's moral and psychological conflicts.

Famous Quotes

Ty Ty Walden: 'There's gold in this ground, I tell ya! My granddaddy wouldn't have lied!'

Griselda Walden: 'Some folks are born to dig, and some are born to be dug under.'

Dave Dawson: 'You can't eat gold, Mr. Walden. You can't plant it neither.'

Ty Ty Walden: 'God's little acre... that's what this is. And I'm gonna find what's buried in it.'

Pluto Walden: 'We're all digging our own graves, one way or another.'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where Ty Ty Walden leads his family in a ritualistic digging ceremony, establishing the family's obsession with finding buried gold while their cotton crops wither in the background.

- The controversial bathtub scene featuring Tina Louise, which was considered highly provocative for 1958 and became one of the most talked-about moments in the film.

- The climactic confrontation scene where family secrets are finally revealed and the truth about the buried gold comes to light, destroying the family's illusions.

- The sequence where Dave Dawson and Griselda Walden meet secretly in the barn, their forbidden attraction captured through subtle gestures and meaningful glances.

- The final scene where Ty Ty Walden must face the consequences of his obsession, standing amid the holes he has dug across his ruined farm.

Did You Know?

- The original 1933 novel by Erskine Caldwell was banned in several U.S. cities and considered scandalous for its depiction of sexuality and poverty in the rural South.

- Tina Louise made her film debut in this movie, though she would become much more famous later for her role as Ginger on Gilligan's Island.

- Jack Lord, who played Dave Dawson, would later become a television icon as Steve McGarrett in Hawaii Five-O.

- Director Anthony Mann was primarily known for his westerns and film noirs, making this rural drama somewhat of a departure from his usual fare.

- The film was one of the last major productions to face serious censorship battles under the Hays Code, which would be replaced by the MPAA rating system just a few years later.

- Robert Ryan was initially reluctant to take the role of Ty Ty Walden, fearing it was too similar to other rural characters he had played.

- The film's title comes from a biblical reference to a small piece of land that God cares for, ironically contrasting with the Walden family's neglect of their farm.

- Despite its adult themes, the film was marketed with a surprisingly light-hearted tone in some promotional materials.

- The production had to create artificial Georgia heat by filming during California's summer months with minimal air conditioning on set.

- Several scenes were cut from the final version, including more explicit sexual content and a longer sequence showing the family's extreme poverty.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception was mixed but generally positive, with many reviewers praising the film's boldness while criticizing its melodramatic elements. The New York Times noted that the film 'pushes the boundaries of what's acceptable in mainstream cinema' but found the story somewhat contrived. Variety appreciated the performances, particularly Robert Ryan's 'towering presence' as the obsessed patriarch. Modern critics have reassessed the film more favorably, recognizing its historical importance in pushing cinematic boundaries. The film is now often cited as an example of late-1950s Hollywood's attempts to address adult themes within the studio system. Some contemporary critics have noted that while the film seems tame by today's standards, it was remarkably progressive for its time in its treatment of sexuality and rural poverty.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1958 responded positively to the film's scandalous reputation, with many drawn to theaters by the controversy surrounding its sexual content. The film performed reasonably well at the box office, particularly in urban areas where audiences were more receptive to adult themes. Some audience members were shocked by the film's frankness, while others appreciated its realistic portrayal of rural struggles. The film developed a cult following over the years, with many viewers appreciating its historical significance as a boundary-pushing production. Modern audiences often view the film as a fascinating time capsule of late-1950s American cinema, capturing the transition period between the restrictive Hays Code era and the more permissive filmmaking of the 1960s.

Awards & Recognition

- Golden Globe Award for Best Newcomer - Tina Louise (won)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Grapes of Wrath (1940)

- A Streetcar Named Desire (1951)

- Baby Doll (1956)

- Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958)

- Erskine Caldwell's controversial literary works

This Film Influenced

- Cool Hand Luke (1967)

- The Last Picture Show (1971)

- The Grapes of Wrath (1973 TV movie)

- Tender Mercies (1983)

- The Burning Plain (2008)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved by Warner Bros. in their film archive and was released on DVD as part of the Warner Archive Collection. While no official restoration has been announced, the existing prints are in good condition and the film is readily available for viewing. The original negative is stored in the Warner Bros. vaults, ensuring the film's long-term preservation.