Homunculus

"Der Mensch ohne Liebe - Eine Tragödie unserer Zeit" (The Man Without Love - A Tragedy of Our Time)"

Plot

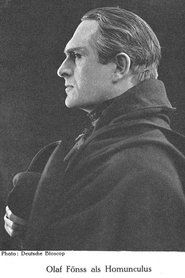

In this groundbreaking German silent science fiction epic, Professor Ortmann and his team of scientists successfully create a human being through artificial means, producing a perfect specimen they name the Homunculus. Played by Olaf Fønss, this artificial man possesses all human capabilities and intelligence but is tragically unable to experience love or emotional connection, making him an outcast despite his physical perfection. As the Homunculus grows aware of his emotional limitations, he becomes increasingly bitter and resentful toward his creators and society, leading him on a destructive path across multiple episodes. The story follows his journey from laboratory creation to a powerful figure seeking revenge on humanity, ultimately questioning what it truly means to be human. The film explores themes of scientific hubris, the nature of consciousness, and the essential role of love in human existence through its ambitious multi-part narrative.

Director

Otto RippertAbout the Production

The film was shot and released in six separate parts between August and December 1916, each part functioning as both an independent episode and part of a larger narrative. This episodic format was innovative for its time and allowed for a more complex character development than typical feature films of the era. The production utilized early special effects techniques to create the laboratory scenes and scientific experiments, which were considered quite advanced for 1916.

Historical Background

Homunculus was produced in 1916, during the third year of World War I, a period that profoundly affected German society and culture. The war had led to increased government control over film production, with authorities viewing cinema as a potential tool for morale and propaganda. However, despite this climate, Homunculus managed to explore philosophical themes rather than overt wartime messaging. The film emerged during a crucial period in German cinema's development, when the industry was beginning to establish its artistic identity separate from French and American influences. This period would eventually give rise to German Expressionism, and Homunculus contains elements that foreshadow that movement's interest in psychological themes and visual stylization. The scientific themes in the film reflected contemporary public fascination with rapid technological advances and the ethical questions they raised, issues that were particularly relevant during a war being fought with increasingly sophisticated weapons and technologies.

Why This Film Matters

Homunculus holds a significant place in cinema history as one of the earliest feature-length science fiction films and a foundational work in the mad scientist genre that would later include Frankenstein and Metropolis. The film's exploration of artificial intelligence and the nature of humanity was remarkably prescient, anticipating themes that would become central to science fiction throughout the 20th century. Its episodic structure influenced later serial films and television series, demonstrating how complex narratives could be sustained across multiple installments. The film also contributed to the development of German cinema's distinctive visual style, which would culminate in the Expressionist movement of the 1920s. Homunculus represents an early example of cinema's ability to tackle philosophical questions about science, ethics, and human nature, establishing a template for thoughtful science fiction that continues to influence the genre today. The character of the emotionally incomplete artificial being has become an archetype in science fiction, appearing in various forms in countless subsequent works.

Making Of

The production of Homunculus was remarkably ambitious for its time, requiring extensive planning and coordination across its six-part structure. Director Otto Rippert worked closely with cinematographer Carl Hoffmann to create visual effects that would convincingly portray the scientific experiments and the Homunculus's creation. The laboratory sets were among the most elaborate constructed in German cinema up to that point, featuring complex electrical equipment, glass vessels, and scientific apparatus that suggested the cutting-edge nature of the experiments. Olaf Fønss's performance required him to portray a character who was physically perfect but emotionally stunted, a challenging feat in silent cinema where facial expression was paramount. The production team reportedly consulted with scientific advisors to ensure the laboratory sequences appeared authentic to contemporary audiences. The film was shot during the height of World War I, which created logistical challenges for the production but also meant that German cinema was experiencing a period of relative isolation from international influences, allowing for the development of uniquely German cinematic styles.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Homunculus, handled by Carl Hoffmann, employed several innovative techniques for its time. The film made extensive use of chiaroscuro lighting to create dramatic contrasts between the sterile laboratory environments and the emotional turmoil of the characters. Hoffmann utilized multiple camera angles and movements that were advanced for 1916, including tracking shots during the Homunculus's journey sequences. The laboratory scenes featured carefully composed shots that emphasized the artificial nature of the creation process, with geometric arrangements of scientific equipment creating a sense of order and control. The cinematography also made effective use of close-ups to capture the subtle emotions of the characters, particularly the Homunculus's struggle with his emotional limitations. The visual style of the film contains elements that would later be developed more fully in German Expressionist cinema, particularly in its use of light and shadow to create psychological atmosphere.

Innovations

Homunculus featured several technical achievements that were notable for 1916. The film's special effects for the creation sequences were particularly innovative, using early techniques such as multiple exposure and dissolves to suggest the artificial formation of human life. The laboratory sets incorporated working electrical effects and chemical reactions that would have appeared quite convincing to contemporary audiences. The film's makeup effects for the Homunculus were subtle but effective, suggesting his artificial nature through subtle rather than grotesque means. The production also employed advanced editing techniques for its time, including cross-cutting between parallel action sequences and the use of montage to show the passage of time. The film's ambitious six-part structure required careful continuity planning and was technically challenging to produce consistently over several months of shooting. These technical innovations helped establish German cinema's reputation for technical excellence that would continue throughout the 1920s.

Music

As a silent film, Homunculus would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The specific musical scores used are not documented in surviving records, but it was common for films of this era to be accompanied by a pianist or small orchestra playing a mixture of classical pieces and original compositions. The emotional tone of the film would have required music that could shift dramatically between the scientific detachment of the laboratory scenes and the tragic pathos of the Homunculus's journey. German theaters of this period often employed skilled musicians who could improvise appropriate accompaniment based on the action on screen. Modern screenings of surviving fragments typically feature newly composed scores that attempt to recreate the musical atmosphere of the 1910s while incorporating contemporary understanding of the film's themes and significance.

Famous Quotes

As an artificial being, I can think but not feel, reason but not love - am I therefore less than human?

You gave me life but withheld the very essence of living - the capacity to love.

In creating perfection, you forgot the imperfect beauty of a human heart.

Science can create form, but only nature can grant soul.

I am your masterpiece and your greatest failure - a mind without a heart.

Memorable Scenes

- The laboratory creation sequence where the Homunculus first opens his eyes, combining scientific apparatus with theatrical lighting to create a sense of both wonder and foreboding

- The Homunculus's first encounter with ordinary humans and his realization of his emotional difference, conveyed through Fønss's subtle facial expressions

- The revenge sequence where the Homunculus uses his superior intellect to manipulate society, demonstrating the dangers of an unemotional intelligence

- The final confrontation between creator and creation, questioning the responsibility of scientific discovery

Did You Know?

- Homunculus is considered one of the earliest feature-length science fiction films in cinema history and a precursor to the Frankenstein genre.

- The film was released in six parts: Part 1 (The Creation), Part 2 (The Mystery), Part 3 (The Conspiracy), Part 4 (The Revenge), Part 5 (The Catastrophe), and Part 6 (The End).

- Olaf Fønss, who played the Homunculus, was Denmark's first major movie star and was highly sought after for his expressive acting style in silent films.

- The film's title refers to the concept of homunculus from alchemy and early scientific thought - a miniature human being created through artificial means.

- Despite being made during World War I, the film was not overtly propagandistic, focusing instead on philosophical and scientific themes.

- The film's success led to a 1920 remake, also titled Homunculus, though the original 1916 version is considered superior by film historians.

- Director Otto Rippert was primarily known for crime and adventure films before Homunculus, which became his most celebrated work.

- The film's themes of artificial intelligence and the ethics of scientific creation were remarkably ahead of their time, prefiguring many later science fiction works.

- The laboratory sequences featured elaborate sets and props that were unusually detailed for 1916, reflecting German cinema's growing technical sophistication.

- The film was one of the first to explore the psychological consequences of being 'different' in society, making it an early example of what would later be called 'outsider cinema'.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception to Homunculus was largely positive, with reviewers praising its ambitious scope and sophisticated themes. German film journals of the time noted its technical achievements and the strength of Olaf Fønss's performance, particularly his ability to convey the Homunculus's internal conflict through subtle facial expressions. Some critics found the film's six-part structure innovative, while others felt it made the narrative somewhat fragmented. Modern film historians have reassessed Homunculus as a crucial work in early science fiction cinema, with many considering it ahead of its time in its treatment of artificial intelligence and scientific ethics. Critics today particularly appreciate the film's psychological depth and its influence on later German Expressionist cinema. The film is often cited in scholarly works about early horror and science fiction as a foundational text that helped establish genre conventions that would persist for decades.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception to Homunculus in 1916 was reportedly strong, with the film proving popular enough to justify the complete production of all six parts. Contemporary accounts suggest that audiences were particularly drawn to the film's scientific themes and the moral questions it raised about the limits of human knowledge. The character of the Homunculus resonated with viewers, who found sympathy in his struggle to understand his place in a world where he could not experience basic human emotions. The film's success during wartime suggested that audiences were eager for escapist entertainment that also engaged with deeper philosophical questions. Modern audiences who have had the opportunity to see surviving fragments of the film often remark on its surprisingly sophisticated treatment of its themes and its influence on later science fiction works. The film's reputation among cinephiles has grown over the years, with many considering it a lost masterpiece of early German cinema.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Mary Shelley's Frankenstein

- Goethe's Faust

- Alchemical traditions and the concept of the homunculus

- German Romantic literature

- Contemporary scientific advances and ethical debates

This Film Influenced

- Metropolis (1927)

- Frankenstein (1931)

- The Golem (1920)

- Alraune (1928)

- Blade Runner (1982)

- The Island of Dr. Moreau (1933 and 1996)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Homunculus is considered a partially lost film. While some fragments and still photographs survive in various archives, including the Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv in Berlin, no complete version of all six parts is known to exist. The surviving fragments suggest the film's visual sophistication and thematic depth, making its incomplete status particularly tragic for film historians. Various archives hold different portions of the film, but efforts to reconstruct a complete version have been hampered by the poor condition of surviving elements and the lack of complete documentation of the original editing. The film's status as a partially lost masterpiece has contributed to its legendary reputation in cinema history.