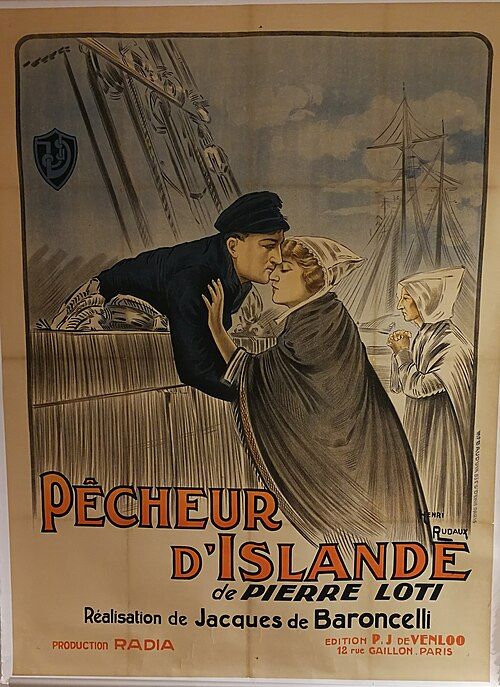

Iceland Fisherman

"L'Amour contre la Mer - Love Against the Sea"

Plot

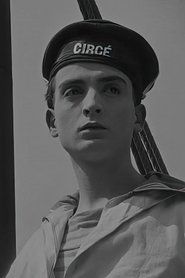

Set in the harsh fishing communities of Brittany, this poignant silent drama follows Yann, a stoic Breton fisherman who makes annual perilous journeys to Iceland's fishing grounds. His devoted wife Gaud waits patiently at home, enduring the long separations and constant fear that accompanies the dangerous profession. When Yann returns from one such voyage, he finds himself torn between his love for Gaud and his deep connection to the sea that has shaped his entire existence. The film faithfully depicts the authentic rituals, superstitions, and hardships of the Breton fishing community, showing how the ocean's call competes with earthly love. As the seasons pass and Yann must choose between another dangerous voyage or staying with his wife, the story explores themes of duty, sacrifice, and the powerful forces that shape human destiny.

About the Production

The film was shot on location in authentic Breton fishing villages, using real fishermen as extras and incorporating actual fishing vessels and equipment. Director Jacques de Baroncelli insisted on filming during the actual fishing season to capture genuine weather conditions and the authentic rhythms of maritime life. The production faced significant challenges including unpredictable North Atlantic weather, which sometimes delayed filming for days. The filmmakers constructed detailed replicas of traditional Breton homes and utilized period-accurate costumes sourced from local communities.

Historical Background

The 1924 release of 'Iceland Fisherman' occurred during a golden age of French cinema, just before the transition to sound would revolutionize the industry. The film emerged from the post-World War I period when French cinema was experiencing a renaissance of artistic ambition and technical sophistication. This was also a time when regional French cultures, particularly those of Brittany, were being romanticized and preserved through literature and film as industrialization threatened traditional ways of life. The film's focus on maritime labor reflected broader European concerns about the working class and the dangers of industrial-era occupations. Pierre Loti's source novel, written in 1886, had become a cultural touchstone for French national identity, representing the stoic character of the French people. The film's release coincided with growing interest in ethnographic cinema and documentary approaches to fictional storytelling.

Why This Film Matters

'Iceland Fisherman' stands as a crucial document of Breton maritime culture, preserving rituals, dialects, and traditions that have since vanished. The film contributed to the romanticization of regional French identity during a period of increasing national homogenization. Its authentic depiction of fishing communities influenced subsequent maritime films and established a template for ethnographic fiction that balanced entertainment with cultural documentation. The movie helped cement the archetype of the stoic, sea-bound French fisherman in popular culture, an image that would recur in French cinema for decades. The film's success demonstrated the commercial viability of regional stories and encouraged other French directors to explore local subjects rather than focusing solely on Parisian narratives. Its preservation of Breton customs, including specific fishing techniques, religious practices, and community celebrations, makes it invaluable for cultural historians.

Making Of

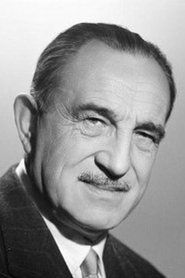

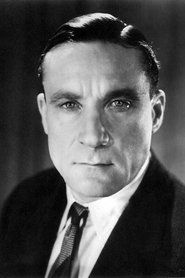

Director Jacques de Baroncelli approached this adaptation with a commitment to anthropological accuracy, spending months in Breton fishing communities before filming began. He insisted on using non-professional actors from local fishing families for many supporting roles to ensure authentic dialects and mannerisms. The production team faced considerable danger filming at sea, with several camera operators nearly swept overboard during storm sequences. Charles Vanel prepared for his role by spending weeks aboard actual fishing vessels, learning the specific techniques and superstitions of Breton fishermen. The film's most challenging sequence involved recreating the dangerous Icelandic fishing grounds, which required the crew to travel to the North Atlantic during the actual fishing season. Many of the maritime scenes were filmed using multiple cameras mounted on different boats to capture the authentic chaos of fishing operations. The production's commitment to realism extended to using traditional Breton costumes that were over 50 years old, sourced from local families who had preserved them as heirlooms.

Visual Style

The cinematography, credited to Maurice Forster and Georges Specht, was revolutionary for its time in its use of natural lighting and authentic maritime locations. The filmmakers employed innovative techniques to capture the drama of the North Atlantic, including mounting cameras on fishing boats during actual storms to achieve unprecedented realism. The visual style contrasted the harsh, gray palette of the sea sequences with the warm, earth tones of the Breton village scenes, creating a powerful visual dichotomy between the two worlds of the protagonist. The film made extensive use of long shots to emphasize the isolation of fishermen at sea and the overwhelming scale of nature. Close-ups were reserved for intimate moments, particularly in scenes between the lovers, creating an emotional counterpoint to the epic maritime sequences. The cinematography also incorporated authentic Breton landscapes and architecture, treating them as characters in the narrative.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations in location filming, particularly in maritime cinematography. The production developed specialized waterproof camera housings that allowed filming in wet conditions and during actual fishing operations. The filmmakers created innovative camera mounts that could be secured to moving fishing vessels without interfering with the crew's work. The film's editing techniques, particularly the cross-cutting between the dangerous fishing voyages and the waiting families on shore, was considered sophisticated for its time. The production also experimented with early color tinting processes, using blue tints for sea sequences and amber tones for domestic scenes to enhance emotional impact. The film's sound effects, created live during screenings, included authentic recordings of sea sounds and fishing activities, representing an early form of synchronized audiovisual presentation.

Music

As a silent film, 'Iceland Fisherman' was originally accompanied by live musical performances that varied by theater. The suggested score, composed by Henri Bérold, incorporated traditional Breton folk melodies and sea shanties to enhance the film's regional authenticity. Major Parisian theaters employed full orchestras for the film's run, while smaller venues used piano or organ accompaniment. The score specifically highlighted the contrast between the romantic themes associated with the lovers and the dramatic, dissonant passages accompanying the dangerous fishing sequences. Some theaters in Brittany reportedly used local musicians who performed authentic Breton songs during the screenings. Modern restorations have been accompanied by newly composed scores that attempt to recreate the film's original musical atmosphere while incorporating contemporary sensibilities.

Famous Quotes

The sea gives, and the sea takes away - we are but borrowers in its eternal kingdom

A fisherman's heart is divided between the woman who waits and the ocean that calls

In Brittany, we measure time not by clocks, but by the tides and the seasons

To love a fisherman is to learn the patience of the shore, waiting for what may never return

The Iceland waters are both our salvation and our grave - we accept this bargain with the sea

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic departure sequence where the fishing fleet leaves the Breton harbor at dawn, with families waving farewell from the cliffs

- The terrifying storm sequence filmed on actual fishing boats in the North Atlantic, showing the crew battling enormous waves

- The emotional reunion scene where Yann returns to find his wife Gaud waiting faithfully on the shore

- The traditional Breton wedding ceremony that showcases authentic regional customs and costumes

- The final decision scene where Yann must choose between another dangerous voyage or staying with his family

Did You Know?

- This was the third film adaptation of Pierre Loti's 1886 novel, following earlier versions in 1913 and 1919

- Charles Vanel, who played Yann, would later become one of France's most celebrated actors, starring in films like 'The Wages of Fear' (1953)

- Director Jacques de Baroncelli was particularly drawn to maritime subjects, having previously made several films about fishing communities

- The film's authentic depiction of Breton culture led to it being used as a cultural document by ethnographers studying traditional maritime life

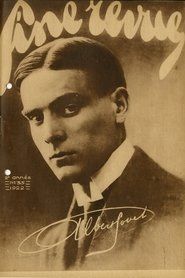

- Sandra Milovanoff, who played Gaud, was one of the most popular French actresses of the 1920s and often starred in romantic dramas

- The production company Société des Cinéromans was known for adapting literary works and was co-founded by novelist Arthur Bernède

- Real Icelandic fishing sequences were filmed using actual Breton fishermen who made the annual journey to Iceland

- The film's intertitles were written by noted playwright and screenwriter Henri Bataille

- Contemporary critics praised the film for its documentary-like authenticity in depicting fishing techniques and maritime traditions

- The movie was one of the last major French silent films before the transition to sound began in the late 1920s

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film for its breathtaking authenticity and emotional power, with many noting that de Baroncelli had elevated the source material through his cinematic vision. Le Petit Parisien called it 'a magnificent tribute to the courage of our Breton fishermen' while Cinéa magazine highlighted its 'unprecedented realism in depicting maritime life.' Modern critics have reevaluated the film as a masterpiece of silent French cinema, particularly noting its sophisticated use of location shooting and natural performances. The film is often cited in film studies as an early example of documentary-influenced fiction filmmaking. Recent restoration screenings have earned praise for the film's timeless emotional resonance and its value as a cultural artifact. Critics have also noted how the film transcends its period through its universal themes of love, duty, and the human relationship with nature.

What Audiences Thought

The film was a commercial success upon its release, particularly resonating with audiences in coastal regions of France who recognized their own communities and struggles depicted on screen. Parisian audiences were drawn to the exoticism of Breton culture and the dramatic maritime sequences. The film's emotional core struck a chord with post-war French audiences who understood themes of separation and sacrifice. Word-of-mouth about the film's spectacular ocean scenes and authentic fishing sequences helped sustain its theatrical run for several months. The film developed a cult following among maritime communities, where it was sometimes screened annually as part of local festivals. In recent decades, the film has found new audiences through revival screenings at classic film festivals and museum retrospectives, where contemporary viewers have praised its timeless beauty and emotional depth.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Pierre Loti's 1886 novel 'Pêcheur d'Islande'

- French naturalist literature of the late 19th century

- Early ethnographic documentary traditions

- German expressionist cinema's emotional intensity

- Nordic literary traditions of sea narratives

This Film Influenced

- The 1939 French sound remake 'Pêcheur d'Islande'

- Marcel Pagnol's maritime trilogy 'Marius', 'Fanny', and 'César'

- Jean Epstein's Breton documentaries

- Robert Bresson's 'A Man Condemned'

- Contemporary Breton cinema focusing on maritime themes

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film exists in various archives, with the most complete version held at the Cinémathèque Française. Several scenes remain lost or damaged, particularly some of the most dangerous maritime sequences. The film underwent a major restoration in the 1990s by the French Film Archives, which combined elements from different prints to create the most complete version available. Some original tinting has been preserved, though not all color effects survive. The restoration work revealed that the film was originally longer than previously believed, with approximately 10 minutes of footage still missing. The film is occasionally screened at classic film festivals and museum retrospectives using the restored version.