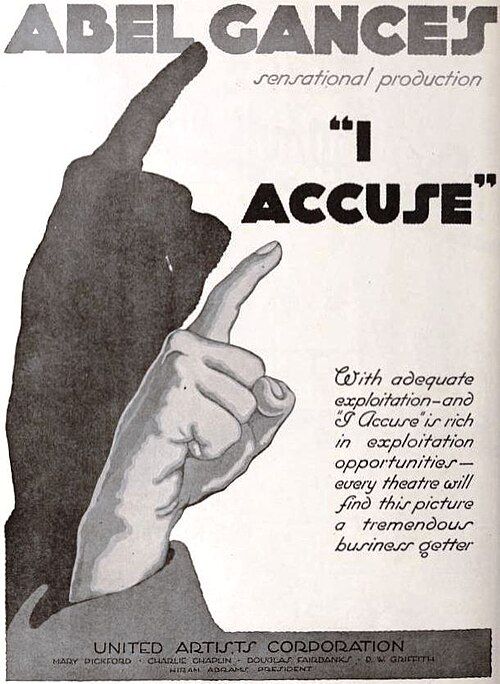

J'accuse

"I accuse... war!"

Plot

François Laurin, a sensitive French poet, marries the beautiful Edith but discovers she is having an affair with his close friend Jean Diaz. The love triangle is interrupted when both men are called to serve in World War I, where they encounter the brutal reality of trench warfare. In the mud and blood of the battlefield, the two rivals reconcile as comrades-in-arms, sharing the horrors of war together. After Jean is killed in action, François returns home to find Edith dying from illness, having learned of Jean's death. The film culminates in its most famous sequence, where the dead soldiers rise from their graves and march back to their villages to question whether their sacrifice was justified.

About the Production

Abel Gance used actual French soldiers who had recently returned from the front as extras in the battle sequences. The production faced numerous challenges including filming in difficult weather conditions and recreating authentic trench warfare. The famous 'return of the dead' sequence required innovative special effects techniques for the time, including multiple exposures and careful choreography of hundreds of extras.

Historical Background

Produced immediately following World War I, 'J'accuse' emerged during a period of profound national trauma in France. The war had claimed over 1.3 million French lives and left the nation physically and emotionally scarred. Cinema was still establishing itself as a serious art form, and Gance's ambitious work demonstrated the medium's potential for social commentary. The film's release coincided with the Treaty of Versailles negotiations and widespread questioning of the war's purpose and meaning. Its anti-war message resonated deeply with a population struggling to make sense of the unprecedented destruction. The film also reflected the Dadaist and surrealist movements beginning to emerge in European art, questioning traditional narratives and embracing experimental techniques.

Why This Film Matters

'J'accuse' stands as one of cinema's earliest and most powerful anti-war statements, establishing conventions that would influence war films for decades. Its innovative techniques, particularly the 'return of the dead' sequence, demonstrated cinema's capacity for surreal and allegorical storytelling. The film helped establish French cinema as a serious artistic medium capable of addressing profound social issues. Its blend of personal drama and epic war narrative created a template for later war films like 'All Quiet on the Western Front' and 'Paths of Glory.' The movie also represents an early example of cinema as political activism, using the popular medium to question authority and challenge nationalist narratives. Its influence extends beyond war films to any cinema dealing with trauma, memory, and social responsibility.

Making Of

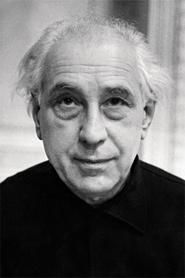

Abel Gance conceived 'J'accuse' while serving in the French Army during WWI, where he witnessed the horrors of trench warfare firsthand. Determined to create an anti-war statement, he began writing the script while still in uniform. The production was grueling, with Gance pushing his cast and crew to their limits. For the battle scenes, he recruited hundreds of actual soldiers who had recently returned from the front, lending an authenticity that couldn't be faked. The most challenging sequence was the 'return of the dead,' which required months of planning and revolutionary special effects techniques. Gance used multiple exposures, careful lighting, and had to direct hundreds of extras in precise movements to create the ghostly effect of soldiers rising from their graves. The emotional toll on the cast and crew was immense, as many were still processing their own wartime experiences.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Léonce-Henri Burel was revolutionary for its time, featuring dynamic camera movements that were highly unusual in 1919. Gance employed handheld cameras for battle sequences, creating a visceral, documentary-like quality that immersed viewers in the chaos of combat. The film used innovative lighting techniques, particularly in the 'return of the dead' sequence, where ghostly effects were achieved through careful manipulation of natural and artificial light. Burel's work included dramatic close-ups that conveyed emotional intensity, tracking shots that followed soldiers through trenches, and sweeping panoramic views of battlefields. The contrast between intimate domestic scenes and epic war sequences demonstrated a mastery of scale and composition that influenced cinematography for decades.

Innovations

Gance pioneered numerous technical innovations in 'J'accuse' that were years ahead of their time. The film's most famous achievement was the 'return of the dead' sequence, which used multiple exposure techniques to create the illusion of soldiers rising from their graves. Gance also employed rapid editing, montage sequences, and superimposition effects that would influence Soviet montage theory. The battle sequences featured practical effects with real explosions and artillery, creating unprecedented realism. The film's use of location shooting in actual battlefields was unusual for the period. Gance experimented with camera movement, including tracking shots and what might be considered early forms of the crane shot. The film's epic scale, with hundreds of extras and massive sets, demonstrated cinema's capacity for spectacle previously thought impossible.

Music

As a silent film, 'J'accuse' was originally accompanied by live musical performances that varied by theater. The score typically included classical pieces, popular songs of the era, and original compositions. For the famous 'return of the dead' sequence, theaters often used somber, funereal music to enhance the emotional impact. Modern restorations have featured newly composed scores by contemporary composers, including orchestral arrangements that attempt to capture the film's epic scope and emotional depth. The original French premiere featured a specially commissioned score by Arthur Honegger, though this music has been lost. The absence of dialogue actually enhanced the film's universal message, allowing the visual storytelling to transcend language barriers.

Famous Quotes

J'accuse... la guerre! (I accuse... war!)

Dead men, why have you returned? To see if your sacrifice was worthwhile.

In the mud of the trenches, all men are brothers.

We died for nothing... or did we die for everything?

The living must answer to the dead.

Memorable Scenes

- The 'return of the dead' sequence where hundreds of ghostly soldiers rise from their battlefield graves and march home to question the living about their sacrifice

- The brutal trench warfare sequences showing the chaos and horror of combat

- The love triangle confrontation before the men leave for war

- The final scene where the protagonist confronts the reality of his losses

- The poet's transformation from romantic idealist to hardened soldier

Did You Know?

- Abel Gance was so passionate about the project that he financed part of it himself

- The title 'J'accuse' references Émile Zola's famous letter defending Alfred Dreyfus

- Many of the soldier extras were actual WWI veterans who had recently returned from combat

- Gance filmed additional scenes in 1938 for a sound remake, but the original silent version is considered the masterpiece

- The film's famous 'return of the dead' sequence was shot in reverse to create the supernatural effect

- Gance contracted Spanish flu during production but continued filming

- The battle sequences used real explosives and artillery, making them dangerously authentic

- Some scenes were filmed on actual WWI battlefields still showing signs of the recent conflict

- The film was initially censored in some countries for its graphic war content

- Gance's innovative camera techniques included handheld shots and dynamic tracking movements

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised 'J'accuse' as a masterpiece of cinematic art and moral courage. French critics hailed it as 'the most important film of the year' and praised Gance's innovative techniques and powerful anti-war message. International critics were equally impressed, with British and American reviews noting its technical achievements and emotional power. Modern critics consider it a landmark of silent cinema, with particular praise for its ambitious scope and the famous 'return of the dead' sequence. The film is frequently cited in lists of the greatest films ever made and is studied in film schools for its technical innovations and narrative complexity. Recent restorations have allowed contemporary critics to fully appreciate Gance's visionary direction and the film's enduring relevance.

What Audiences Thought

The film was enormously popular with post-war French audiences, many of whom were veterans or had lost family members in the conflict. Reports from the time describe audiences weeping during screenings and standing in ovation, particularly during the 'return of the dead' sequence. Veterans' organizations endorsed the film for its honest portrayal of the war experience. The commercial success was significant for an art film of its era, running for months in Paris cinemas. International audiences also responded positively, though some countries initially censored or cut the film for its graphic content. Modern audiences viewing restored versions continue to be moved by its power and technical brilliance, with screenings at film festivals and revival houses often selling out.

Awards & Recognition

- Grand Prix du Cinéma Français (1919)

- Medal of Honor from the French Veterans Association (1919)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Émile Zola's 'J'accuse'

- D.W. Griffith's 'The Birth of a Nation' (for epic scale)

- Georges Méliès (for special effects techniques)

- French realist literature

- Expressionist art movement

This Film Influenced

- All Quiet on the Western Front

- Paths of Glory

- The Big Parade

- Westfront 1918

- Come and See

- Apocalypse Now

- Saving Private Ryan

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved and restored by various archives including the Cinémathèque Française. Multiple versions exist, with the most complete restoration completed in recent years. Some footage remains lost, but the majority of the film survives in watchable condition. The 1938 sound remake used some footage from the original, helping preserve certain sequences. Digital restorations have made the film accessible to modern audiences while preserving its historical and artistic integrity.