Kansas City Confidential

"The Most Daring Robbery Ever Filmed!"

Plot

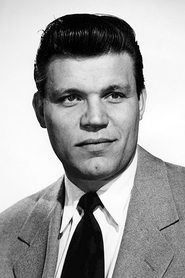

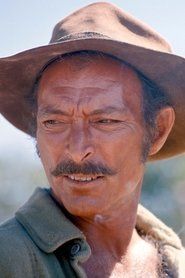

Ex-convict Joe Rolfe (John Payne) runs a flower delivery business in Kansas City, trying to rebuild his life after serving time for a crime he didn't commit. His world is shattered when three masked criminals hijack an armored car using a vehicle identical to his delivery truck, framing him for the robbery. After police interrogation clears him but leaves his reputation ruined, Joe becomes obsessed with tracking down the real culprits. He follows their trail to Mexico where he discovers the robbery was masterminded by a retired police captain (Preston Foster) and involves three other criminals who don't know each other's identities. Joe infiltrates their gang by taking the place of one of the original robbers, working alongside the victim's daughter Helen (Coleen Gray) to expose the criminals and clear his name, leading to a tense confrontation where loyalties are tested and justice is sought.

About the Production

The film was shot in just 24 days on a tight budget. Director Phil Karlson used innovative camera techniques, including handheld shots during action sequences, which was uncommon for the time. The armored car robbery sequence was particularly challenging to film, requiring precise timing and coordination between multiple cameras and stunt performers. John Payne, who typically starred in musicals and lighter fare, specifically sought this role to transition to more serious dramatic work.

Historical Background

Released in 1952 during the height of the film noir era, 'Kansas City Confidential' emerged during a period of post-war anxiety and social change in America. The early 1950s saw increased public fascination with organized crime and police corruption, fueled by real-life investigations like the Kefauver hearings. The film's themes of identity theft and wrongful conviction resonated with audiences concerned about the growing complexity of modern life and the potential for ordinary people to be caught in systems beyond their control. The Cold War era's paranoia about hidden enemies and deception also influenced the film's narrative of masked criminals and mistaken identity. This was also a time when Hollywood was experimenting with more realistic and gritty storytelling, moving away from the more polished productions of the 1940s.

Why This Film Matters

'Kansas City Confidential' is considered a quintessential example of film noir and has influenced countless crime films that followed. Its innovative use of masked criminals who don't know each other's identities became a trope in heist films, most notably seen in Quentin Tarantino's 'Reservoir Dogs.' The film's exploration of an ex-convict seeking redemption while operating outside the law helped establish the anti-hero archetype that would become central to 1960s and 1970s cinema. Its realistic approach to violence and urban decay predated the more graphic films of the late 1960s. The movie's success demonstrated the commercial viability of low-budget, high-intensity crime thrillers, paving the way for similar productions throughout the decade. It remains a touchstone for filmmakers studying the noir genre and is frequently cited in film studies courses as an example of narrative efficiency and visual storytelling.

Making Of

The production faced several challenges during filming, including a tight 24-day shooting schedule and limited budget. Director Phil Karlson insisted on using real locations whenever possible and employed innovative camera techniques to give the film a gritty, documentary feel. The armored car robbery sequence required extensive planning and took three days to film perfectly. John Payne, eager to shed his musical comedy image, performed many of his own stunts, including a dangerous fall from a moving vehicle. The film's realistic approach to violence was controversial at the time, with the Production Code office demanding several cuts to reduce the brutality. Karlson fought to maintain the film's tough edge, arguing that the violence was essential to the story's realism. The relationship between Payne and Karlson was initially tense but evolved into mutual respect as they worked together to create a more authentic crime film.

Visual Style

The cinematography, by George E. Diskant, employs classic noir techniques including high-contrast lighting, deep shadows, and unusual camera angles to create a mood of urban menace and moral ambiguity. Diskant used low-angle shots to emphasize the power dynamics between characters and employed Dutch angles during moments of psychological tension. The film's visual style is characterized by its use of natural light in exterior scenes and carefully constructed shadows in interior sequences. The armored car robbery sequence features innovative camera work, including what appears to be handheld shots that give the scene a documentary-like immediacy. The Mexico sequences use bleached-out lighting to create a sense of foreignness and danger, while the Kansas City scenes emphasize the cold, impersonal nature of urban life through industrial imagery and stark architectural compositions.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations that would become standard in later crime films. The use of multiple cameras during the armored car robbery sequence allowed for dynamic coverage and maintained continuity during complex action scenes. Director Phil Karlson employed what he called 'psychological editing,' using quick cuts and jarring transitions to reflect the protagonist's mental state. The film's sound design was particularly advanced for its time, featuring layered audio that created a realistic urban environment. The production team developed new techniques for filming night scenes that required less artificial lighting, giving the film a more authentic nocturnal atmosphere. These technical achievements were particularly impressive given the film's limited budget and tight shooting schedule.

Music

The film's score was composed by Paul Sawtell, who created a tense, jazz-influenced soundtrack that perfectly complemented the noir atmosphere. Sawtell used dissonant brass and rhythmic percussion to build suspense during action sequences, while employing melancholic piano themes for moments of introspection. The music eschews traditional romantic themes in favor of a more urban, contemporary sound that reflects the film's gritty realism. Notably, the score uses minimal leitmotifs, instead relying on mood and texture to enhance the narrative. The sound design is particularly effective in the robbery sequence, where the lack of musical score creates heightened tension through the use of natural sounds and silence. This approach was innovative for its time and influenced the use of sound in subsequent crime thrillers.

Famous Quotes

"I'm not a killer. I'm just a man who's been pushed too far." - Joe Rolfe

"In my business, you learn to trust your instincts, not people." - Mr. Fenninger

Sometimes the only way to get justice is to take it yourself." - Joe Rolfe

"A man's reputation is all he's got when he's got nothing else." - Joe Rolfe

"In this town, you're either the hunter or the hunted. There's no in-between." - Mr. Fenninger

Memorable Scenes

- The armored car robbery sequence where three masked men execute a perfectly timed heist using a vehicle identical to the protagonist's delivery truck, establishing the central conflict.

- The police interrogation scene where John Payne's character is aggressively questioned, showcasing his transformation from innocent victim to determined seeker of justice.

- The tense Mexico border crossing where Joe infiltrates the criminal gang by assuming the identity of one of the original robbers.

- The final confrontation in the Mexican villa where all the criminals finally meet face-to-face and the mastermind is revealed.

Did You Know?

- The film's title was changed from 'Kansas City Story' to 'Kansas City Confidential' to capitalize on the public's fascination with crime and mystery stories.

- John Payne invested his own money in the production, showing his commitment to breaking away from his previous musical comedy image.

- The film was remade in 1996 as 'Kansas City' with the same basic premise but updated characters and setting.

- Director Phil Karlson was known for his tough, realistic approach to crime films and brought documentary-style techniques to this production.

- The mask designs used by the criminals were intentionally made to look like common everyday items to emphasize the 'everyman' nature of the criminals.

- Preston Foster, who plays the mastermind, was actually older than John Payne despite playing his antagonist.

- The film's success led to a unofficial 'trilogy' of similar films including '99 River Street' (1953) and 'The Phenix City Story' (1955), all directed by Karlson.

- The armored car used in the robbery was an actual modified vehicle that had been used in real security operations.

- Coleen Gray's role was originally written for a more established star, but Karlson fought to cast her after being impressed by her screen test.

- The film's Mexico sequences were filmed on the same backlot sets used for many other 'south of the border' productions of the era.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film for its taut direction and realistic approach to crime drama. The New York Times highlighted John Payne's effective dramatic transformation, while Variety noted the film's 'punchy narrative and expert pacing.' Modern critics have reevaluated the film as a minor masterpiece of film noir, with many considering it one of director Phil Karlson's finest works. Film scholar Eddie Muller has called it 'a perfect example of how to make a compelling crime thriller on a budget.' The film's reputation has grown over time, with particular praise for its innovative structure, where the protagonist hunts down criminals who remain anonymous to each other, creating a unique tension that distinguishes it from other noir films of the era.

What Audiences Thought

The film was a moderate box office success upon release, particularly popular in urban markets where crime dramas had strong appeal. Audiences responded positively to John Payne's performance, with many noting his successful transition from lighter fare to serious drama. The film's tight pacing and clear-cut revenge narrative resonated with post-war audiences who appreciated straightforward storytelling with moral clarity. Over the decades, the film has developed a cult following among film noir enthusiasts and is frequently screened at revival theaters and film festivals. Modern audiences often cite it as an example of efficient, no-nonsense filmmaking that delivers maximum impact with minimal resources. The film's availability on home video and streaming platforms has introduced it to new generations of viewers who appreciate its gritty realism and influence on later crime films.

Awards & Recognition

- National Board of Review Award for Best Actor (John Payne, 1952)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Big Sleep (1946)

- The Killers (1946)

- Out of the Past (1947)

- The Asphalt Jungle (1950)

This Film Influenced

- Reservoir Dogs (1992)

- Heat (1995)

- The Usual Suspects (1995)

- Kansas City (1996)

- The Town (2010)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved by the UCLA Film and Television Archive and was restored by the Criterion Collection for home video release. While the original negative has some deterioration, a high-quality preservation copy exists. The film entered the public domain in the United States, which has led to numerous DVD releases of varying quality. The best available version is the Criterion Collection edition, which features a 4K restoration from the best surviving elements.