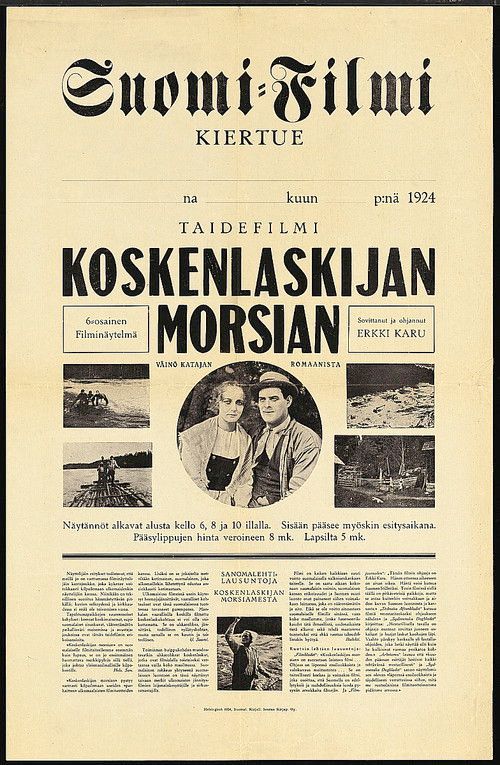

Koskenlaskijan morsian

"Suuri suomalainen koskenlaskudraama – jännitystä, romantiikkaa ja luonnonvoimia!"

Plot

In the rural village of Nuottaniemi, the elderly Iisakki lives with his beautiful daughter Hanna, harboring a deep-seated bitterness toward his neighbor Heikki, whom he blames for the tragic death of his son in a timber rafting accident years prior. The tension escalates when Heikki's son, Juhani, seeks Hanna's hand in marriage to unite their lands, but Hanna is deeply in love with Antti, a rugged and skilled lumberjack who represents the free spirit of the rapids. As the rivalry between the families reaches a breaking point, a dangerous timber rafting competition is organized where the men must prove their worth against the lethal currents of the river. The climax sees Antti risking his life in the roaring waters to save his rival, ultimately forcing Iisakki to confront his past trauma and decide between a legacy of hate or a future of forgiveness for his daughter's happiness.

About the Production

The production was exceptionally ambitious for the time, utilizing the dangerous Siikakoski rapids for its most harrowing sequences. Director Erkki Karu insisted on realism, which meant the actors and stuntmen faced genuine physical peril during the timber rafting scenes. The film was based on the popular 1914 novel by Väinö Kataja, which had already established a strong cultural footprint in Finland. The production faced significant logistical challenges transporting heavy camera equipment to remote river locations, often requiring the crew to build temporary platforms over the water to capture the action.

Historical Background

Produced only six years after Finland gained independence from Russia in 1917, the film served as a vital tool for nation-building and cultural identity. It showcased the Finnish landscape—specifically the forests and rapids—as a source of both national pride and formidable challenge. The 1920s were a period of 'Agrarian Romanticism' in Finnish art, where the struggle of the rural peasant and the logger was elevated to heroic status. This film arrived at a time when Finland was trying to prove its cultural sophistication to the rest of Europe, using its unique geography as a cinematic calling card.

Why This Film Matters

The film is a cornerstone of Finnish film history, establishing the 'lumberjack film' (tukkilaiselokuva) as a distinct and beloved national genre. It defined the archetype of the Finnish hero: stoic, hardworking, and capable of mastering the violent forces of nature. For decades, the imagery of the man balancing on a log in the middle of a roaring rapid became synonymous with Finnish resilience. It also marked the professionalization of the Finnish film industry, proving that local productions could compete with high-quality imports from Sweden and Hollywood.

Making Of

The making of 'Koskenlaskijan morsian' was a testament to Erkki Karu's vision of creating a 'National Cinema' for the newly independent Finland. Karu and his cinematographer Frans Ekebom spent weeks scouting the perfect rapids that would provide both visual grandeur and the necessary danger for the plot's climax. During filming, the cast and crew lived in primitive conditions near the river sites, often battling unpredictable weather and the sheer physical exhaustion of the river shoots. Konrad Tallroth, who played Iisakki, was himself a distinguished director, and his presence on set provided a veteran stability to the production. The editing process was particularly rigorous, as Karu sought to match the rhythmic pulse of the rushing water with the emotional beats of the family drama.

Visual Style

Frans Ekebom utilized deep focus and wide shots to emphasize the scale of the Finnish landscape compared to the human characters. The use of natural light in the forest sequences creates a soft, romantic atmosphere that contrasts sharply with the high-contrast, fast-cut editing of the rapids sequences. The camera was often placed dangerously close to the water level to give the audience a visceral sense of the river's speed and power, a technique that was highly innovative for 1923.

Innovations

The film is notable for its sophisticated editing during the climax, which uses rhythmic cutting to build tension—a technique influenced by the Soviet montage school but applied to a narrative drama. The production also successfully managed complex outdoor logistics, including the use of multiple camera angles to capture a single 'run' down the rapids, which was a significant technical feat given the size and weight of 1920s hand-cranked cameras.

Music

As a silent film, it originally premiered with live orchestral accompaniment. In modern restorations, a score based on Finnish folk motifs and the works of Jean Sibelius is often used to complement the nationalistic themes. The original 1923 screenings in Helsinki featured a specially curated selection of classical and folk pieces performed by a full cinema orchestra.

Famous Quotes

Iisakki: 'The river took my son, and it was your father's hand that guided the timber!' (Intertitle describing the central grudge)

Antti: 'The rapids do not fear any man, but a man must not fear the rapids if he wants to live.' (Intertitle establishing the protagonist's philosophy)

Hanna: 'My heart belongs to the river-man, not to the land-owner.' (Intertitle expressing her defiance of the arranged marriage)

Memorable Scenes

- The Climax in the Rapids: Antti and Juhani are forced to navigate the most dangerous part of the river. The sequence uses real footage of men on logs in white water, creating a sense of genuine danger that remains thrilling today.

- The Opening Vista: A sweeping panoramic shot of the Finnish lake district that established the 'National Romantic' visual style of the film.

- The Reconciliation: The final scene where Iisakki finally shakes hands with his rival over the rushing water, symbolizing the end of the old feud and the birth of a new era.

Did You Know?

- This was the first major international breakthrough for Finnish cinema, being exported to over 10 countries including the USA and Germany.

- The film features genuine timber rafters (tukkijätkät) as extras to ensure the authenticity of the river-working scenes.

- Lead actress Heidi Blåfield was one of the biggest stars of the Finnish silent era, but tragically died of paratyphoid fever only a few years after this film's release.

- The film was so popular that it was remade twice: once in 1937 by Valentin Vaala and again in 1958 by Aarne Tarkas.

- Director Erkki Karu founded Suomi-Filmi, the studio that produced this film, which became the dominant force in Finnish cinema for decades.

- The 'stunt' work in the rapids was performed without modern safety equipment, relying on the actual skills of the local river workers.

- The film's American release was titled 'The Logfloater's Bride'.

- It is considered the definitive example of the 'National Romantic' style in Finnish silent film.

- The cinematography was handled by Frans Ekebom, who was a pioneer of Finnish outdoor photography.

- The film's success helped secure the financial future of Suomi-Filmi during a volatile economic period.

What Critics Said

Upon its release in 1923, critics hailed it as a 'triumph of Finnish spirit' and praised the technical execution of the rapids scenes as being on par with international standards. The Swedish press, usually critical of Finnish efforts, noted the film's 'raw power and authentic atmosphere.' Modern critics view it as a masterpiece of the silent era, noting that while the acting style is occasionally melodramatic by today's standards, the cinematography and location work remain breathtakingly effective and visually modern.

What Audiences Thought

The film was a massive 'blockbuster' of its day, with reports of sold-out screenings across Finland for months. Audiences were particularly moved by the realistic depiction of the timber rafting, a profession many Finns had a personal connection to at the time. It became a cultural touchstone that families would go to see together, reinforcing the film's themes of reconciliation and the beauty of the Finnish wilderness.

Awards & Recognition

- Honorary recognition at the 1923 Nordic Film Congress

- Posthumous recognition in various Finnish Cinema Retrospectives as a 'Masterpiece of the Silent Era'

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The novels of Väinö Kataja

- Swedish 'Golden Age' cinema (Victor Sjöström and Mauritz Stiller)

- Finnish National Romantic painting (Akseli Gallen-Kallela)

This Film Influenced

- Koskenlaskijan morsian (1937)

- Koskenlaskijan morsian (1958)

- The Milkmaid (1949)

- The People of Moomin Valley (various adaptations of rural Finnish life)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been meticulously restored by the National Audiovisual Institute (KAVI) of Finland. A high-definition digital restoration was completed using the original nitrate negatives, ensuring that the stunning cinematography of the rapids is preserved for future generations.