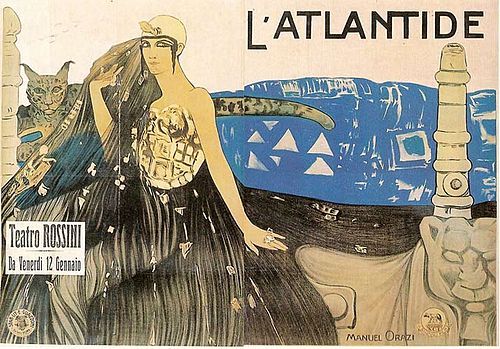

L'Atlantide

"Le mystérieux royaume d'Atlantide vous attend au cœur du désert"

Plot

Two French officers, Capt. de Saint-Avit and Lt. Morhange, become lost in the vast Sahara Desert after their patrol is attacked by Tuareg warriors. They discover the hidden kingdom of Atlantis, a magnificent underground city ruled by the immortal and seductive Queen Antinea. The queen, who has lived for centuries, has a macabre tradition of taking lovers from among the men who discover her kingdom and preserving their bodies as mummies in a crypt after their deaths. Both officers fall under Antinea's spell, with Morhange becoming her favorite, leading to intense jealousy between the men. Saint-Avit, driven by jealousy and love, eventually kills Morhange in a fit of rage, only to realize he has played into Antinea's hands, as she now plans to make him her next victim. The film concludes with Saint-Avit's desperate escape from Atlantis, carrying with him the terrible secret of the lost kingdom and its immortal queen.

About the Production

This was one of the first major French films to use extensive location shooting, with the cast and crew spending months in the harsh conditions of the Sahara. The production faced numerous challenges including extreme heat, sandstorms, and difficulties transporting equipment. Director Jacques Feyder insisted on authentic locations to create the film's atmospheric quality. The elaborate sets for Atlantis were built in Paris but designed to match the desert locations. The film's success helped establish location shooting as a viable technique for French cinema.

Historical Background

Produced in the aftermath of World War I, 'L'Atlantide' emerged during a period when French cinema was struggling to compete with American films that dominated the market. The film's massive scale and exotic themes reflected a broader cultural fascination with colonial adventures and the mysteries of North Africa, which had been intensified by France's colonial expansion in the region. The early 1920s saw a surge of interest in spiritualism and ancient mysteries, and the film tapped into this zeitgeist with its story of an immortal queen and a lost civilization. The film's production also coincided with technical innovations in cinema, including more portable cameras and better film stock, which made location shooting more feasible. Its success demonstrated that French cinema could produce spectacles that could compete with Hollywood epics, helping to revitalize the French film industry during a difficult period.

Why This Film Matters

'L'Atlantide' had a profound impact on both French and international cinema. It established the exotic adventure film as a viable genre in European cinema and influenced countless subsequent films. The character of Queen Antinea became an archetype of the dangerous, seductive woman in cinema, influencing characters from the femme fatale in film noir to various villainesses in later adventure films. The film's success in proving the commercial viability of location shooting opened doors for more ambitious productions in French cinema. It also helped establish the fantasy genre as more than just children's entertainment, showing that fantastical elements could be combined with serious dramatic themes. The film's visual style, particularly its use of light and shadow to create atmosphere, influenced the development of film noir in the following decade. Its international success also helped break down barriers between European film industries, leading to more co-productions and cross-cultural influences.

Making Of

The production of 'L'Atlantide' was groundbreaking for French cinema in its scale and ambition. Director Jacques Feyder, inspired by American epics like 'Intolerance', insisted on shooting in actual desert locations rather than using studio sets. The cast and crew endured extreme conditions, with temperatures often exceeding 120°F (49°C). Stacia Napierkowska, playing Queen Antinea, had to wear elaborate costumes and heavy makeup in the blistering heat. The film's most complex sequences involved the underground kingdom of Atlantis, which required massive sets built at the Joinville studio. Feyder worked closely with cinematographer Léonce-Henri Burel to create the film's distinctive visual style, using innovative lighting techniques to create the mysterious atmosphere of Atlantis. The production was so expensive that it nearly bankrupted the production companies, but its massive commercial success saved them and proved that large-scale French productions could compete internationally.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Léonce-Henri Burel was groundbreaking for its time, particularly in its use of natural light in the desert sequences. Burel employed innovative techniques to capture the vastness and harshness of the Sahara, using wide shots to emphasize the isolation of the characters and extreme close-ups to create psychological tension. The contrast between the bright, harsh light of the desert and the mysterious, shadowy interiors of Atlantis was a key visual motif. Burel used special filters and lighting techniques to create the otherworldly atmosphere of the underground kingdom. The film featured some of the earliest uses of camera movement in French cinema, including tracking shots through the desert and elaborate crane shots in the palace scenes. The cinematography was heavily influenced by German Expressionism in its use of shadows and angular compositions, particularly in the scenes set in Atlantis. The visual style helped establish the film's dreamlike, mysterious quality and influenced the look of many subsequent fantasy films.

Innovations

The film was technically innovative in several ways. It was one of the first French films to use extensive location shooting, demonstrating that portable cameras and equipment could be used effectively in remote locations. The production pioneered new techniques for filming in extreme heat and harsh desert conditions. The special effects used to create the underground kingdom of Atlantis were advanced for their time, using a combination of matte paintings, miniatures, and forced perspective to create the illusion of a vast underground city. The film also featured innovative use of superimposition and multiple exposure techniques, particularly in scenes showing the ghostly appearances of Antinea's former lovers. The makeup effects for the mummified bodies were particularly realistic and disturbing for the period. The film's editing techniques, including cross-cutting between parallel storylines, helped create suspense and maintain narrative momentum. These technical achievements helped establish new standards for French film production and influenced many subsequent films.

Music

As a silent film, 'L'Atlantide' was originally accompanied by live musical performances. The score was composed by Henri Rabaud, who was then director of the Paris Conservatory. Rabaud's orchestral score was designed to enhance the film's exotic atmosphere, incorporating elements of North African musical themes alongside traditional European orchestral music. The score featured prominent use of strings and woodwinds to create a sense of mystery and romance, with percussion instruments used during the desert sequences to evoke the sounds of the Sahara. Different theaters used various approaches to the musical accompaniment, with larger cinemas employing full orchestras while smaller venues used piano or organ. Some contemporary screenings have featured newly composed scores by modern composers who have attempted to recreate the spirit of Rabaud's original music while incorporating contemporary musical elements.

Famous Quotes

Antinea: 'In Atlantis, time does not exist. Only desire, and its fulfillment.'

Saint-Avit: 'We came seeking water, but found instead the eternal thirst of forbidden love.'

Morhange: 'To die in her arms is not death, but immortality of another kind.'

Antinea: 'All men who find their way to me become mine forever - in life and in death.'

Saint-Avit: 'The desert gives no second chances, and neither does the Queen of Atlantis.'

Memorable Scenes

- The first reveal of Atlantis as the exhausted officers descend into the hidden kingdom

- Queen Antinea's dramatic entrance in her throne room, surrounded by her mummified former lovers

- The tense confrontation between Saint-Avit and Morhange in the desert oasis

- The climactic escape sequence as Saint-Avit flees Atlantis with the Queen's guards in pursuit

- The haunting final scene showing Saint-Avit's return to civilization, forever changed by his experience

Did You Know?

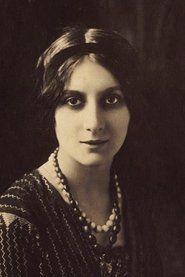

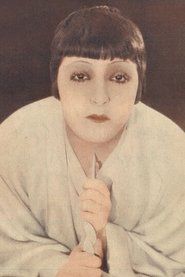

- Stacia Napierkowska, who played Queen Antinea, was a famous dancer and actress known as 'the Polish goddess' before this role

- The film was so popular in Germany that it directly led to the German remake 'Die Herrin von Atlantis' in 1932

- Pierre Benoit, the author of the original novel, was reportedly very pleased with the adaptation

- The desert scenes were filmed without permits, as the French colonial authorities were initially skeptical of the project

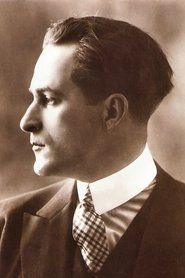

- Georges Melchior, who played Saint-Avit, was one of France's most popular leading men of the silent era

- The mummification scenes were considered shocking for the time and caused some controversy

- The film's success inspired a wave of exotic adventure films in French cinema throughout the 1920s

- Queen Antinea's costume became an iconic image of 1920s cinema fashion

- The film was one of the first to use the technique of cross-cutting between desert scenes and the underground kingdom

- A young Jean Renoir reportedly worked as an assistant on the film, though this is disputed by some film historians

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised 'L'Atlantide' for its ambitious scope and visual beauty. French critics hailed it as a triumph of national cinema, with Le Film Complet calling it 'a masterpiece of French imagination and technical skill.' The film was particularly admired for its photography and the performance of Stacia Napierkowska as Antinea. International critics were also impressed, with The New York Times praising its 'magnificent photography and thrilling narrative.' Modern critics and film historians view the film as a landmark of silent cinema, noting its influence on the adventure genre and its technical innovations. Some contemporary scholars have re-examined the film through a postcolonial lens, critiquing its orientalist themes while acknowledging its artistic achievements. The film is now recognized as a crucial work in the development of fantasy and adventure cinema, and as an important example of 1920s French visual style.

What Audiences Thought

The film was an enormous commercial success upon its release, breaking box office records in France and performing exceptionally well internationally. Audiences were captivated by the exotic locations, the mysterious story of Atlantis, and the hypnotic performance of Stacia Napierkowska. The film's combination of adventure, romance, and mystery appealed to a wide range of viewers. In France, it ran for months in major cities and helped revitalize public interest in French films. Its success in Germany was particularly notable, where it became one of the most popular foreign films of the decade. Audiences were especially drawn to the film's spectacular visuals and the enigmatic character of Queen Antinea. The film's popularity led to increased demand for exotic adventure films throughout the 1920s. Even today, when screened at film festivals and revival houses, the film continues to captivate audiences with its atmospheric storytelling and visual grandeur.

Awards & Recognition

- Médaille d'or du cinéma français (1921)

- Prix du meilleur film français at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs (1925)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Pierre Benoit's novel 'L'Atlantide' (1919)

- German Expressionist cinema (particularly 'The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari')

- D.W. Griffith's 'Intolerance' (1916)

- Ancient Greek myths of Atlantis

- Orientalist literature and art of the 19th century

- The adventure novels of Jules Verne and H. Rider Haggard

This Film Influenced

- The Thief of Bagdad (1924)

- She (1925)

- Die Herrin von Atlantis (1932) - German remake

- Lost Horizon (1937)

- The Naked Jungle (1954)

- Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981)

- The Mummy (1999)

- National Treasure (2004)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in several archives worldwide, including the Cinémathèque Française in Paris and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. While some scenes show signs of deterioration, a significant portion of the original film survives. A restored version was completed in 1995 using materials from various archives, though some sequences remain incomplete. The restoration process involved digital cleaning and color tinting restoration based on original distribution materials. The film is considered one of the better-preserved examples of early 1920s French cinema, though some original footage is believed to be lost, particularly from the opening sequences.