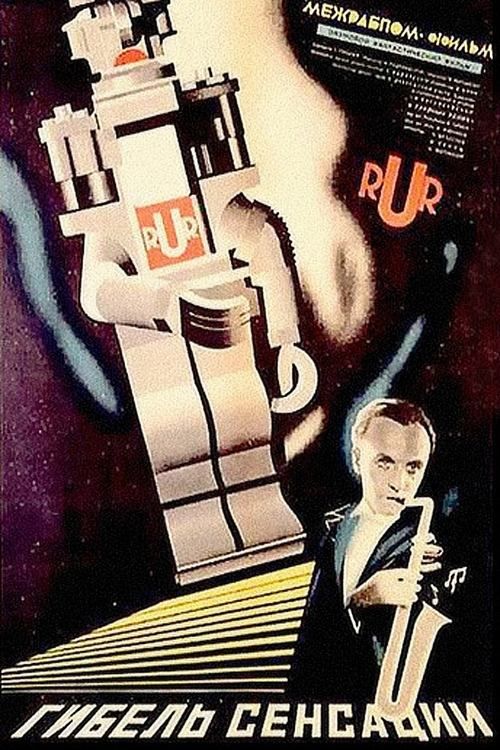

Loss of Feeling

"The machines that promised to free humanity instead enslaved it to war"

Plot

In an unnamed capitalist country, brilliant young engineer Jim Kroll invents giant, inexhaustible robots designed to replace fragile human workers on high-volume assembly lines. His creation promises to revolutionize industry, but the military-industrial complex quickly co-opts his invention for weapons production. As the robots are repurposed for war manufacturing, Kroll becomes increasingly disillusioned with how his humanitarian invention has been corrupted by capitalist greed and militarism. The film culminates in a powerful critique of automation divorced from human welfare, as Kroll witnesses his dream of helping workers transform into a nightmare of mechanized warfare.

About the Production

The film featured elaborate mechanical robot costumes and props that were remarkably sophisticated for 1935. The production team built full-scale robot models that could move mechanically, representing some of the most ambitious special effects work in Soviet cinema at the time. The factory sequences were filmed in actual industrial plants to achieve maximum authenticity.

Historical Background

Made during the height of Stalin's First Five-Year Plan, 'Loss of Feeling' emerged during a period of rapid industrialization in the Soviet Union. The 1930s saw massive technological advancement and factory construction across the USSR, alongside growing concerns about the dehumanizing effects of industrial labor. The film reflected contemporary debates about automation, worker alienation, and the military applications of technology. Its production coincided with the rise of fascist regimes in Europe, adding urgency to its anti-militarist message. The film's brief banning in 1937 reflected the increasingly paranoid cultural atmosphere of the Great Purge, when even ideologically correct works could be condemned for perceived pessimism.

Why This Film Matters

As one of the earliest Soviet science fiction films with explicit social commentary, 'Loss of Feeling' pioneered the use of genre elements to explore ideological concerns. It prefigured later Cold War-era science fiction that would use robots and automation as metaphors for political systems. The film's sophisticated visual effects and production design influenced subsequent Soviet science fiction productions. Its critique of technology divorced from human welfare remains relevant in contemporary discussions about AI and automation. The film represents an important but often overlooked chapter in the history of Soviet cinema's engagement with science fiction.

Making Of

The production faced significant challenges in creating the robot effects, as the Soviet film industry had limited experience with science fiction elements. Director Andriyevsky consulted with engineers and factory workers to ensure the industrial sequences felt authentic. The cast, particularly Sergei Vecheslov who played the idealistic engineer, spent time studying real engineers to understand their mindset. The film's critique of automation reflected genuine debates within Soviet society about the role of technology in building socialism, with some party officials concerned the film's message was too critical of industrial progress.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Grigory Giber featured dramatic contrasts between the cold, mechanical world of the factory and the few remaining human spaces. The film used innovative camera techniques to emphasize the scale of the robots, including low angles and forced perspective. The industrial sequences employed documentary-style realism, reflecting Andriyevsky's background in non-fiction filmmaking. The visual style incorporated elements of German Expressionism, particularly in the robot sequences, while maintaining the socialist realist aesthetic required for Soviet productions of the era.

Innovations

The film's most significant technical achievement was its creation of convincing robot effects using 1930s technology. The production team developed innovative mechanical puppetry techniques that allowed for complex robot movements. The factory sequences featured elaborate miniature models combined with full-scale sets to create a sense of industrial scale. The film pioneered certain editing techniques for action sequences involving mechanical characters. The sound design created distinctive audio signatures for the robots that enhanced their mechanical nature. These technical innovations represented some of the most ambitious special effects work in Soviet cinema of the period.

Music

The musical score was composed by Dmitri Kabalevsky, who would later become one of the Soviet Union's most prominent composers. The music incorporated industrial sounds and mechanical rhythms to reinforce the film's themes. The soundtrack used leitmotifs to distinguish between human and machine elements, with the robot sequences featuring dissonant, mechanical-sounding orchestration. The film's limited sound technology of the era presented challenges in creating convincing mechanical sound effects, which were achieved through creative use of everyday objects and musical instruments.

Famous Quotes

I built these machines to free men from labor, not to build instruments of their destruction.

The perfect worker feels no pain, asks no questions, and needs no rest. But is that what we want humanity to become?

In their quest for efficiency, they have forgotten that machines should serve men, not replace them.

Memorable Scenes

- The unveiling sequence where the giant robots are first demonstrated to factory executives, featuring impressive special effects and dramatic cinematography that emphasizes their imposing scale and mechanical nature

Did You Know?

- This was one of the earliest Soviet science fiction films to explicitly critique capitalism and automation

- The robot designs were influenced by Fritz Lang's 'Metropolis' (1927) but given a distinctly Soviet ideological interpretation

- The film was briefly banned in 1937 during Stalin's purges for being 'too pessimistic' about technological progress

- Director Aleksandr Andriyevsky was primarily known for documentaries, making this one of his rare narrative features

- The English title 'Loss of Feeling' was a translation of the original Russian title 'Poterya chuvstv'

- The film featured one of the earliest depictions of what we would now call androids or humanoid robots in cinema

- Despite its Soviet origins, the film was set in an unnamed Western country to better critique capitalist systems

- The mechanical robot effects were achieved using a combination of actors in costumes and full-scale mechanical puppets

- The film's pessimistic view of automation was unusual for Soviet cinema of the 1930s, which typically celebrated technological progress

- Only partial prints of the film survive today, with some sequences existing only in still photographs

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film's technical achievements and bold social commentary, though some found its pessimism problematic. The film was noted for its impressive special effects and strong performances, particularly by Vecheslov. Western critics who saw the film during its limited international release were impressed by its sophisticated approach to science fiction themes. Modern film historians recognize 'Loss of Feeling' as an important early example of socially conscious science fiction, though its incomplete preservation status has limited scholarly analysis. The film is now regarded as a significant precursor to later works exploring the relationship between technology and labor.

What Audiences Thought

Initial Soviet audiences responded positively to the film's spectacular robot sequences and factory settings, though some found its critique of automation confusing given the official celebration of industrial progress. The film's limited release and subsequent banning meant it never achieved wide popular recognition. Modern audiences who have seen the surviving fragments are often struck by how contemporary its themes feel, particularly its concerns about automation and military applications of technology. The film has developed a cult following among enthusiasts of early science fiction and Soviet cinema.

Awards & Recognition

- None documented - the film's controversial reception likely prevented official recognition

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Metropolis (1927)

- Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

- Soviet industrial documentaries of the 1930s

- German Expressionist cinema

This Film Influenced

- The Mechanical Monsters (1941)

- Soviet science fiction films of the 1960s

- Modern films about AI and automation

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Partially preserved - only fragments of the film survive, with some sequences known only through still photographs and production documents. The complete original version is considered lost, though restoration efforts continue using existing fragments and contemporary accounts.