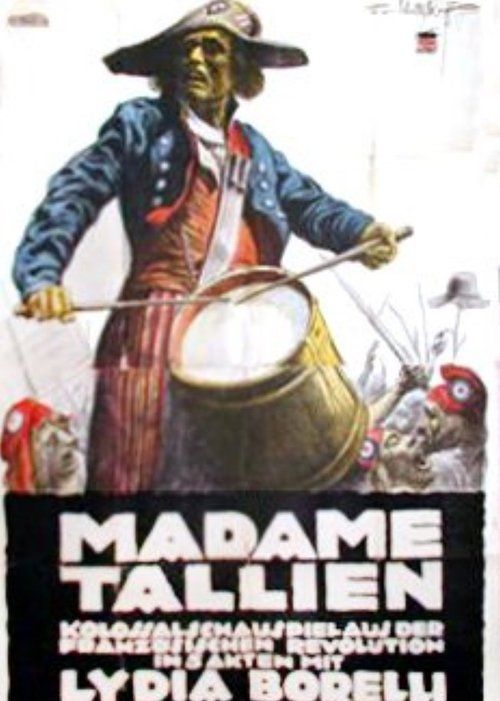

Madame Guillotine

"La femme qui fit tomber Robespierre"

Plot

Madame Guillotine (also known as Madame Tallien) follows the tumultuous life of Thérésa Tallien, a prominent figure during the French Revolution who navigates the dangerous political landscape through her wit, charm, and strategic alliances. The film depicts her rise from imprisonment during the Reign of Terror to becoming an influential salonnière who used her connections to save numerous aristocrats from execution. Her romantic entanglements with powerful men, including Jean-Lambert Tallien and Napoleon Bonaparte, are portrayed alongside her political machinations that ultimately contributed to Robespierre's downfall. The narrative explores how she transformed from victim to victor, using her beauty and intelligence as weapons in a time when women had little formal power. The film culminates with her instrumental role in ending the Terror, earning her the nickname 'Notre-Dame de Thermidor' among her contemporaries.

About the Production

This was one of the most expensive Italian productions of 1916, featuring elaborate period costumes and sets recreating revolutionary Paris. The film used innovative lighting techniques for dramatic effect, particularly in the guillotine scenes. Lyda Borelli's wardrobe reportedly cost the equivalent of several thousand dollars, an enormous sum for the time.

Historical Background

Produced during World War I, Madame Guillotine emerged at a time when Italian cinema was experiencing its golden age, competing with French and American films for international markets. The film's exploration of revolutionary themes resonated with contemporary European audiences living through unprecedented political upheaval. Italy's own involvement in the war, along with rising social tensions, made the French Revolution setting particularly relevant. The film reflected the era's fascination with historical epics that could comment on contemporary issues through the safe distance of period drama. The production coincided with the rise of the 'diva' film in Italian cinema, where female stars like Lyda Borelli became powerful cultural icons.

Why This Film Matters

Madame Guillotine represents a pinnacle of the Italian diva film genre, showcasing Lyda Borelli's star power and the sophisticated visual style of Italian silent cinema. The film contributed to the international image of Italian cinema as a producer of lavish historical epics. It influenced subsequent French Revolution films across Europe and established a template for female-led historical dramas. Borelli's performance as Madame Tallien became iconic, influencing fashion and beauty standards of the 1910s. The film's portrayal of a politically powerful woman was progressive for its time, reflecting early 20th-century debates about women's roles in society. Its technical achievements in lighting and set design influenced other European productions of the period.

Making Of

The production faced numerous challenges due to World War I, including rationing of film stock and restrictions on outdoor filming. Director Mario Caserini reportedly clashed with star Lyda Borelli over her interpretation of Madame Tallien's character, with Borelli insisting on a more sympathetic portrayal than initially scripted. The elaborate ballroom sequences took weeks to film, requiring dancers to practice for hours in period costumes that weighed up to 40 pounds. The guillotine scenes were so realistic that some crew members reportedly fainted during filming. Caserini employed innovative camera techniques for the time, including tracking shots during the crowd scenes and dramatic close-ups of Borelli, which were uncommon in Italian cinema of the period.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Angelo Scalenghe was groundbreaking for its use of dramatic lighting, particularly in the execution scenes where he employed chiaroscuro effects to heighten tension. The film featured elaborate tracking shots through the revolutionary crowds, a technical innovation for Italian cinema. Scalenghe used soft focus techniques for Borelli's close-ups, creating an ethereal quality that enhanced her diva status. The ballroom sequences utilized multiple lighting sources to create depth and movement, while the prison scenes used stark, high-contrast lighting to emphasize the characters' desperation. The cinematography helped establish the visual language of Italian historical epics.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations in Italian cinema, including the use of artificial lighting to simulate daylight for interior scenes. The production employed a complex system of mirrors and reflectors to achieve dramatic lighting effects, particularly in the guillotine sequences. The set design featured moving platforms and elevators to create dynamic crowd scenes. The film's editing style, with its rapid cross-cutting between parallel actions, was advanced for its time. The production also experimented with color tinting, using blue tones for night scenes and red for the revolutionary sequences.

Music

As a silent film, Madame Guillotine was accompanied by live musical scores during its original run. The Italian premiere featured a specially commissioned orchestral score by composer Edoardo Mascheroni, which incorporated revolutionary French songs and classical themes. Different theaters used various musical accompaniments, ranging from solo piano to full orchestra. The score emphasized dramatic moments with thunderous percussion during the guillotine scenes and romantic strings for Borelli's appearances. Modern restorations have used period-appropriate classical music to recreate the original viewing experience.

Famous Quotes

The revolution needs lovers as much as it needs soldiers.

When heads roll, hearts must remain steady.

I have loved many men, but I have served only France.

In the shadow of the guillotine, we learn what truly matters.

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic guillotine sequence where Madame Tallien dramatically intervenes to save prisoners

- The elaborate ballroom scene where Tallien dances with Robespierre while plotting his downfall

- The prison confrontation where Tallien uses her charm to secure her release

- The final scene showing Tallien watching Robespierre's execution with calculated satisfaction

Did You Know?

- Lyda Borelli was one of the highest-paid actresses in Europe at the time, earning approximately 10,000 lire per film

- The film was banned in France for several years due to its controversial portrayal of revolutionary figures

- Director Mario Caserini died shortly after completing this film, making it one of his final works

- The guillotine prop used in the film was reportedly built to exact historical specifications

- Thérésa Tallien's descendants attempted to block the film's release, claiming it defamed their ancestor's memory

- The film featured over 500 extras in the crowd scenes depicting revolutionary Paris

- Original intertitles were written by noted poet Gabriele D'Annunzio, though his contribution was uncredited

- The film was shot during World War I, making production difficult due to material shortages

- A sequel was planned but never produced due to the war and Caserini's death

- The film's success led to a wave of French Revolution-themed films in Italy throughout 1917-1918

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film's visual splendor and Borelli's magnetic performance, with Italian newspapers calling it 'a triumph of national cinema.' French critics were more divided, some accusing it of historical inaccuracy while others admired its dramatic power. Modern film historians consider it an important example of the Italian historical epic genre, though some criticize its melodramatic approach to history. The film is noted in film scholarship for its sophisticated use of lighting and Borelli's performance style, which influenced later silent film acting techniques. Recent restorations have led to renewed appreciation for its artistic merits and historical importance.

What Audiences Thought

The film was a commercial success across Europe, particularly in Italy where it ran for weeks in major cities. Audiences were drawn by Borelli's star power and the film's sensational subject matter. The guillotine scenes became particularly famous, with audiences reportedly gasping and fainting during premieres. The film's international success helped establish Borelli as one of Europe's biggest film stars. Despite its controversial reception in France, it found an audience there when finally released several years later. Modern audiences who have seen restored versions at film festivals have responded positively to its visual beauty and dramatic intensity.

Awards & Recognition

- Medaglia d'oro al valore cinematografico (Gold Medal for Cinematic Merit) - Italian Film Society, 1916

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Cabiria (1914)

- The Last Days of Pompeii (1913)

- Quo Vadis (1913)

- Contemporary French revolutionary literature

This Film Influenced

- Napoleon (1927)

- A Tale of Two Cities (various adaptations)

- The Scarlet Pimpernel (1934)

- Marie Antoinette (1938)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was considered lost for decades until a partial print was discovered in the Czech National Film Archive in the 1970s. A more complete version was later found in the Italian National Film Archive. The film has been partially restored by the Cineteca di Bologna, though some sequences remain missing. The restored version premiered at the 2012 Venice Film Festival. The preservation status is considered fragile but stable, with digitization efforts ongoing.