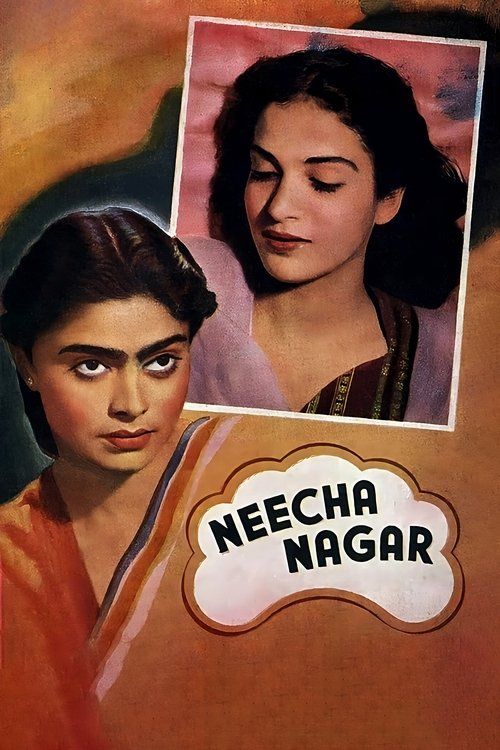

Neecha Nagar

Plot

Neecha Nagar tells the story of a wealthy and powerful landlord named Sarkar who devises a plan to redirect all the sewage and waste from the city into a poor village called Neecha Nagar (Lowly Town). This scheme is part of his larger real estate development project that would displace the impoverished villagers living there. The villagers, led by the idealistic young man Balraj, initially try to reason with Sarkar through peaceful means, but when their pleas are ignored, they organize a protest against his exploitative plans. As the conflict escalates, the film explores the stark class divisions and the struggle of the oppressed against the powerful elite. The narrative culminates in a powerful confrontation between the villagers and Sarkar's forces, highlighting themes of social justice and collective action. The film serves as a powerful allegory for the broader social and political struggles occurring in India during the pre-independence era.

About the Production

Neecha Nagar was made on a very modest budget with a largely amateur cast and crew. The film was shot in just 20 days, a remarkably short timeframe even for that era. Director Chetan Anand, who was making his directorial debut, faced numerous challenges including limited resources and the political sensitivities of making a socially critical film during British colonial rule. The film's realistic style was revolutionary for Indian cinema, which was then dominated by mythological and romantic films. Many scenes were shot on location in actual slums and poor neighborhoods to maintain authenticity, a practice that was uncommon in Indian filmmaking at the time.

Historical Background

Neecha Nagar was created during a pivotal moment in Indian history - the final years of British colonial rule. India was on the cusp of independence (which came in 1947), and the country was experiencing intense political and social upheaval. The 1940s saw the rise of various social movements addressing issues of poverty, caste discrimination, and workers' rights. The film emerged from this environment of heightened social consciousness and reflected the growing demand for artistic works that addressed real social issues rather than providing escapist entertainment. The immediate post-World War II period also saw a global shift toward more realistic and socially conscious cinema, with Italian neorealism emerging around the same time. The film's international recognition at Cannes came at a time when Indian cinema was virtually unknown outside the subcontinent, making its success particularly significant for establishing India's presence on the world cinema stage.

Why This Film Matters

Neecha Nagar holds immense cultural significance as a pioneering work that established India's credentials in international cinema. Its victory at the first Cannes Film Festival demonstrated that Indian cinema could compete with the best in the world and tell stories with universal appeal. The film broke new ground by addressing social inequality and class struggle directly, paving the way for socially conscious cinema in India. It influenced generations of Indian filmmakers, particularly those associated with the Indian Parallel Cinema movement of the 1950s-1970s, including Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, and Ritwik Ghatak. The film's realistic style, location shooting, and focus on marginalized communities became hallmarks of this movement. Additionally, Neecha Nagar challenged the conventions of mainstream Indian cinema, which was then dominated by mythological stories and romantic fantasies, proving that films with serious social themes could also achieve artistic and critical success.

Making Of

The making of Neecha Nagar was as revolutionary as the film itself. Chetan Anand, having returned from England with progressive ideas about cinema, wanted to create a film that addressed social issues rather than providing mere entertainment. He gathered a group of like-minded artists, many of whom were from the Indian People's Theatre Association (IPTA), a cultural organization with leftist leanings. The film was shot with minimal resources, with many crew members working for nominal fees out of belief in the project's social message. The casting was particularly noteworthy - Rafiq Anwar, who played Balraj, was a theater actor making his film debut. The film's realistic approach extended to its dialogue, which incorporated colloquial language and reflected how people actually spoke in the depicted communities. The production faced some censorship challenges from British authorities due to its themes of class struggle and social injustice, but the filmmakers managed to navigate these issues by framing the story as a universal human drama rather than direct political commentary.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Neecha Nagar, handled by Bimal Roy, was revolutionary for its time and marked a significant departure from the theatrical style prevalent in Indian cinema. Roy employed natural lighting and location shooting to create a gritty, realistic atmosphere that reflected the harsh living conditions of the villagers. The camera work was characterized by its documentary-like approach, with many scenes shot in actual slums and poor neighborhoods. The use of deep focus and wide-angle shots helped establish the social context and emphasized the collective nature of the villagers' struggle. The visual composition often contrasted the opulent lifestyle of Sarkar with the squalid conditions of Neecha Nagar, using lighting and framing to highlight the stark class divisions. The film's visual style was influenced by international cinema movements, particularly the emerging neorealist approach in Italy, making it one of the earliest examples of realistic cinematography in Indian cinema.

Innovations

Neecha Nagar achieved several technical milestones for Indian cinema in the 1940s. The film pioneered location shooting in Indian cinema, moving away from the studio-bound productions that were the norm. This required innovative approaches to lighting and sound recording in uncontrolled environments. The film's editing style, which favored longer takes and observational sequences over rapid cuts, was influenced by international cinema and was relatively sophisticated for its time. The sound recording techniques used to capture authentic ambient sounds on location were advanced for the period. The film also demonstrated innovative approaches to set design, with many scenes shot in actual locations rather than constructed sets. The cinematography employed techniques such as deep focus and naturalistic lighting that were cutting-edge for Indian cinema. These technical innovations not only served the film's artistic vision but also expanded the possibilities of filmmaking in India, influencing subsequent generations of filmmakers.

Music

The music for Neecha Nagar was composed by Ravi Shankar, who would later become world-renowned as a sitar virtuoso. Unlike typical Indian films of the era, Neecha Nagar had minimal musical elements, with no elaborate song-and-dance sequences. The soundtrack primarily consisted of background music that enhanced the dramatic moments and underscored the emotional intensity of key scenes. Ravi Shankar's score incorporated elements of Indian classical music but was arranged in a more contemporary, Western-influenced style that complemented the film's modernist approach. The restraint shown in the use of music was itself revolutionary, as it broke away from the convention of having numerous songs in Indian films. This musical minimalism helped maintain the film's realistic tone and prevented the narrative from being interrupted by musical interludes, contributing significantly to the film's distinctive artistic identity.

Famous Quotes

When the poor unite, even the mighty must bow before their collective will.

Progress that crushes the weak is not progress, but destruction in disguise.

Our poverty is our crime, and our resistance is our punishment.

In the city of the rich, the poor are but shadows, but in Neecha Nagar, we are the light.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing the stark contrast between the affluent city and the impoverished Neecha Nagar, establishing the film's visual and thematic dichotomy.

- The village meeting where Balraj first calls for resistance against Sarkar's plan, capturing the awakening of collective consciousness.

- The confrontation scene between the villagers and Sarkar's men, where the poor stand united against armed oppression.

- The final scene where the villagers' protest reaches its climax, symbolizing the triumph of human dignity over greed and power.

- The moment when Sarkar tours Neecha Nagar with contempt, his indifference to human suffering visually representing class privilege.

Did You Know?

- Neecha Nagar was the first Indian film to win an award at an international film festival, winning the Grand Prix (now known as Palme d'Or) at the first Cannes Film Festival in 1946.

- The film shared the Grand Prix win with ten other films including 'Brief Encounter' and 'The Lost Weekend' in the inaugural Cannes festival.

- Director Chetan Anand was only 29 years old when he made this film, marking his directorial debut.

- The film was inspired by Maxim Gorky's play 'The Lower Depths' and adapted to an Indian context.

- Uma Anand, who played one of the lead roles, was married to director Chetan Anand and this was her film debut as well.

- The film's title 'Neecha Nagar' literally translates to 'Lowly Town' or 'Lower City,' symbolizing both the physical and social position of the villagers.

- The film was made just one year before India's independence and reflected the growing social consciousness and anti-colonial sentiment of the time.

- Despite its international acclaim, the film was not a commercial success in India, partly due to its serious social themes which differed from the popular entertainment of the era.

- The film's realistic style and social themes influenced the Indian Parallel Cinema movement that emerged decades later.

- Kamini Kaushal, who played the female lead, became one of the most prominent actresses of the 1940s and 1950s after this film.

What Critics Said

At the time of its release, Neecha Nagar received mixed reviews in India, with some critics praising its bold social message while others found it too preachy and lacking in entertainment value. However, its international reception was overwhelmingly positive. The Cannes jury, which included figures like Georges Huisman and Émile Vuillermoz, recognized the film's artistic merit and social relevance. International critics praised its realistic approach and powerful storytelling. In retrospect, film historians and critics have reevaluated Neecha Nagar as a groundbreaking work that anticipated many developments in world cinema. Contemporary critics often cite it as an important precursor to both Italian neorealism and Indian parallel cinema. The film is now studied in film schools and academic courses on world cinema as a landmark achievement in early Indian cinema that successfully combined social consciousness with artistic innovation.

What Audiences Thought

Contemporary audience reception to Neecha Nagar was lukewarm in India, where the film struggled at the box office. Indian audiences in the 1940s were accustomed to musical extravaganzas and romantic dramas, and the film's serious tone and social themes were considered unconventional and somewhat heavy. The lack of songs and dances, which were staples of Indian cinema, also contributed to its limited popular appeal. However, educated urban audiences and progressive intellectuals appreciated the film's message and artistic ambitions. The film's international success at Cannes did generate some interest in India, but this failed to translate into significant commercial success. Over the decades, as Indian audiences became more sophisticated and as the film's historical significance became more apparent, Neecha Nagar has gained appreciation among cinema enthusiasts and is now regarded as a classic that was ahead of its time.

Awards & Recognition

- Grand Prix (Palme d'Or) at the first Cannes Film Festival, 1946

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Maxim Gorky's play 'The Lower Depths'

- Italian neorealism (though this film preceded its full emergence)

- Indian People's Theatre Association (IPTA) ideology

- Marxist social theory

- Pre-independence Indian social reform movements

- Documentary film techniques

- International socially conscious cinema of the 1930s-40s

This Film Influenced

- Do Bigha Zameen (1953)

- Pather Panchali (1955)

- Mother India (1957)

- The World of Apu (1959)

- Various Indian Parallel Cinema films of the 1960s-80s

- Socially conscious films of the Indian New Wave

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Neecha Nagar is partially preserved, though complete high-quality versions are rare. The National Film Archive of India (NFAI) has preserved some prints of the film, though they may not be in pristine condition due to the age of the original negatives. The film's historical significance has led to efforts to restore and preserve it, but the process has been challenging due to the limited resources available for preserving classic Indian cinema. Some restored versions have been shown at film festivals and retrospectives, helping to keep this important work accessible to contemporary audiences. The film's status as India's first internationally recognized cinematic achievement has made its preservation a priority for film archivists and cultural institutions.