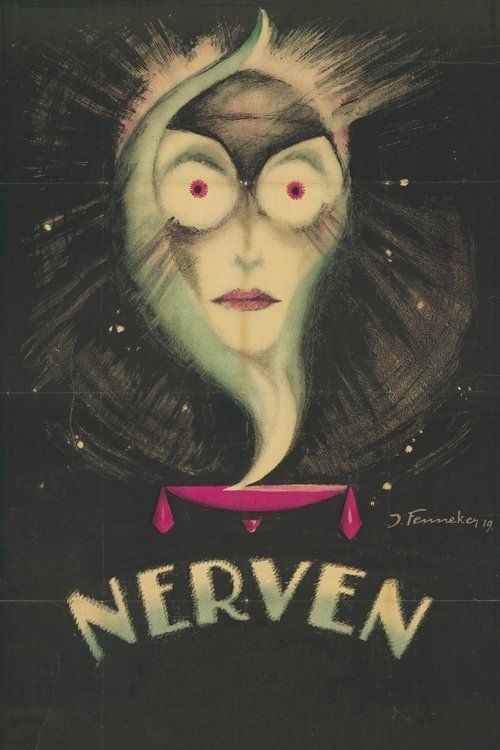

Nerves

"A Portrait of the Nervous Epidemic That Drives a Nation Mad"

Plot

Nerves (Nerven) is a powerful German expressionist drama that explores the psychological breakdown of society in the aftermath of World War I. The film follows three interconnected characters representing different facets of German society: factory owner Roloff, who descends into madness as he witnesses social collapse and worker unrest; teacher John, who emerges as a charismatic leader of the masses seeking radical change; and Marja, a young woman who transforms into a fervent revolutionary after experiencing personal tragedy. Set against the backdrop of Munich in 1919, the film depicts a society gripped by what the director calls a 'nervous epidemic' - a collective hysteria born from war trauma, economic devastation, and political instability. The narrative weaves through increasingly chaotic scenes of street violence, factory strikes, and mass demonstrations, ultimately questioning whether revolution is the cure or merely another symptom of society's nervous breakdown.

About the Production

Filmed on location in Munich during the actual period of political unrest and revolutionary activity, giving the film unprecedented authenticity. The production took place during the Bavarian Soviet Republic period, adding real tension to the filming. Reinert used non-professional actors for some crowd scenes to capture genuine revolutionary fervor. The film's controversial content led to censorship battles in several German states.

Historical Background

Nerves was produced during one of the most turbulent periods in German history - the immediate aftermath of World War I and the German Revolution of 1918-1919. The film captures the essence of a nation grappling with defeat, economic collapse, political fragmentation, and the psychological trauma of four years of brutal warfare. Munich, where the film was shot, was particularly volatile, experiencing the short-lived Bavarian Soviet Republic in 1919. The Weimar Republic was in its infancy, facing challenges from both communist revolutionaries and right-wing reactionaries. This period saw massive hyperinflation, widespread unemployment, and a pervasive sense of national humiliation. The film's depiction of a 'nervous epidemic' was not merely metaphorical; it reflected genuine medical concerns about the psychological impact of the war on the German population, including what we would now recognize as PTSD. The film emerged alongside the German Expressionist movement in art and cinema, which sought to express the inner turmoil and anxiety of the post-war period through distorted visuals and emotional intensity.

Why This Film Matters

Nerves stands as a crucial document of post-war German cinema and society, representing one of the earliest cinematic attempts to address collective psychological trauma. The film predates and influences the German Expressionist movement that would dominate German cinema in the early 1920s, with its focus on psychological states and social anxiety. Its innovative use of location shooting and naturalistic performances helped establish a more realistic approach to filmmaking that contrasted with the stylized studio productions of the era. The film's balanced portrayal of different social classes and political perspectives made it remarkably progressive for its time, avoiding the propaganda tendencies that would characterize much of German cinema in the following decade. Nerves has been studied by film historians as an early example of cinema engaging with social psychology and mass movements, predating similar explorations in Soviet cinema. Its influence can be seen in later German films dealing with social unrest and psychological breakdown, including G.W. Pabst's The Joyless Street and Fritz Lang's Metropolis.

Making Of

Robert Reinert approached Nerves with the analytical eye of a physician diagnosing a societal illness. Having served as a medical doctor during World War I, he witnessed firsthand the psychological trauma that afflicted soldiers and civilians alike. The production was remarkably dangerous, with the cast and crew often filming amid real political demonstrations and occasional violence in Munich's streets. Reinert insisted on using natural lighting and real locations whenever possible, a revolutionary approach for 1919 that gave the film its gritty, documentary-like quality. The cast underwent extensive preparation, with Reinert requiring them to study actual case studies of war trauma and nervous breakdowns. Eduard von Winterstein, who played the factory owner Roloff, reportedly experienced genuine psychological distress during the filming of his breakdown scenes, blurring the line between performance and reality. The film's most controversial sequence, depicting a mass revolutionary rally, was filmed during an actual political gathering, with the camera crew barely avoiding arrest by authorities who mistook them for revolutionary propagandists.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Nerves, handled by Carl Hoffmann, was groundbreaking for its time and represents a crucial transitional moment in German film visual style. Hoffmann employed a mixture of location shooting and studio work that created a striking visual contrast between the gritty reality of Munich's streets and the more controlled psychological spaces of interior scenes. The film makes innovative use of handheld camera techniques during the crowd scenes, creating a sense of chaos and immediacy that would influence later documentary and newsreel styles. Lighting was particularly noteworthy, with Hoffmann using natural light for exterior scenes to enhance realism, while employing dramatic shadow work for interior psychological sequences that foreshadowed the German Expressionist aesthetic. The camera work during the revolutionary rally sequences was especially daring, with high-angle shots and dynamic movement that captured the scale and energy of the crowds. The film's visual language successfully bridges the more static compositions of pre-war cinema with the dynamic, psychologically-informed camerawork that would define the German Expressionist movement.

Innovations

Nerves achieved several significant technical innovations for its time. The film's extensive use of location shooting in Munich was revolutionary for 1919, predating similar techniques in other national cinemas. The production employed portable cameras and lighting equipment that allowed for greater mobility in capturing street scenes and mass gatherings. The film's editing, particularly in the revolutionary sequences, used rapid cutting and cross-cutting techniques to build tension and convey the chaos of social breakdown - techniques that were still being developed in cinema at the time. The sound design, while limited by silent film technology, made innovative use of visual cues and intertitles to represent the cacophony of revolutionary crowds. The film also experimented with superimposition and double exposure techniques to represent psychological states, particularly in the sequences depicting Roloff's mental breakdown. These technical achievements, while subtle by modern standards, represented significant steps forward in cinematic language and influenced subsequent German Expressionist films.

Music

As a silent film, Nerves would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical score would have been provided by a theater orchestra or pianist, using compiled classical pieces and original improvisations to match the film's emotional tone. While no original score documentation survives, contemporary accounts suggest that performances used dramatic Wagnerian pieces for the revolutionary scenes and more delicate Romantic compositions for the intimate psychological moments. Modern restorations have been accompanied by newly composed scores, most notably a 1995 restoration featuring an original score by German composer Bernd Schultheis that incorporates period-appropriate musical styles while using modern orchestration to enhance the film's psychological intensity. Some contemporary screenings have used experimental electronic scores to emphasize the film's themes of nervous breakdown and social disintegration.

Famous Quotes

'We are all nerves now, trembling on the edge of madness or revolution.' - Teacher John

'The factory stands empty, but the machines in our heads keep turning.' - Factory owner Roloff

'When the world breaks, we must choose whether to pick up the pieces or shatter it completely.' - Marja

'This nervous epidemic is not a sickness, it is the birth cry of a new world.' - Revolutionary speaker

'In times like these, sanity is the most dangerous form of madness.' - Teacher John

Memorable Scenes

- The revolutionary rally sequence filmed during an actual political demonstration in Munich, where the line between cinema and reality blurred completely

- Factory owner Roloff's psychological breakdown in his empty factory, using innovative camera angles and lighting to convey mental disintegration

- Teacher John's impassioned speech to the workers, combining political rhetoric with psychological insight

- Marja's transformation from grieving widow to radical revolutionary, shown through a series of increasingly intense close-ups

- The final montage sequence intercutting images of industrial machinery with human faces, suggesting the mechanization of society and souls

Did You Know?

- The film was considered so controversial and potentially inflammatory that it was initially banned in several German cities

- Director Robert Reinert was a medical doctor before becoming a filmmaker, which influenced his clinical approach to depicting psychological breakdown

- The film was shot during the actual revolutionary period in Munich, with real political unrest occurring just blocks from filming locations

- Nerves is considered one of the earliest films to explicitly deal with PTSD and mass psychological trauma following World War I

- The film's original German title 'Nerven' was sometimes translated as 'The Nerves' in English markets

- Many of the extras in the revolutionary scenes were actual political activists from Munich's socialist movements

- The film was one of the first German productions to use location shooting extensively rather than relying entirely on studio sets

- Cinematographer Carl Hoffmann would later become famous for his work on Fritz Lang's M and The Big Clock

- The film's depiction of factory owners and workers was so balanced that both left-wing and right-wing critics accused it of favoring the other side

- A significant portion of the original negative was believed lost until a restoration in the 1990s found missing footage in an East German archive

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception to Nerves was deeply divided and often intense. Progressive critics praised the film's bold social commentary and psychological depth, with the Berliner Tageblatt calling it 'a courageous diagnosis of our times.' Conservative publications, however, condemned the film as dangerous and potentially inflammatory, with the Völkischer Beobachter (later the Nazi party newspaper) denouncing it as 'degenerate art that glorifies revolution.' The film's technical achievements, particularly its cinematography and use of location, were universally acknowledged even by its detractors. Modern critics have reevaluated Nerves as a significant work of early German cinema, with film historian Siegfried Kracauer noting its 'prescient understanding of the psychological forces that would shape the coming decade.' The film is now recognized as an important bridge between the pre-war German cinema and the Expressionist masterpieces that would follow, with its blend of social realism and psychological expressionism.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception to Nerves in 1919 was as polarized as the critical response. Working-class audiences in Berlin and Munich reportedly responded enthusiastically to the film's depiction of their struggles, with some screenings erupting in spontaneous political demonstrations. Middle-class viewers were often disturbed by the film's raw portrayal of social collapse, with many walkouts reported during the more intense revolutionary sequences. The film's controversial nature led to it being banned in several German cities, which only increased its notoriety and appeal among those seeking subversive cinema. Despite (or because of) the controversy, the film performed well commercially in major urban centers, though it struggled in more conservative rural areas. Modern audiences at revival screenings and film festivals have responded with fascination to the film's historical authenticity and psychological insight, though some find its pacing and style challenging by contemporary standards.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- German Expressionist art movement

- Medical and psychological theories of the early 20th century

- Karl Marx's writings on class struggle

- Sigmund Freud's psychoanalytic theories

- Gustave Le Bon's 'The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind'

- The real political events of the German Revolution of 1918-1919

- D.W. Griffith's 'Intolerance' (1916) for its multi-narrative structure

This Film Influenced

- The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

- From Morn to Midnight (1920)

- The Joyless Street (1925)

- Metropolis (1927)

- October: Ten Days That Shook the World (1928)

- Kameradschaft (1931)

- The Marriage of Maria Braun (1979)

- The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum (1975)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Nerves was believed to be partially lost for decades, with only fragments surviving in various archives. A major restoration effort in the 1990s located missing footage in the former East German film archives, allowing for a more complete reconstruction of the original 1919 version. The restored version, while still missing some footage, represents approximately 85% of the original film. The restoration was undertaken by the Munich Film Museum and the Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau Foundation, with funding from the German Federal Cultural Foundation. The restored version has been screened at various international film festivals and is available through specialized cinema archives and some streaming services dedicated to classic cinema. The film remains in the public domain due to its age, though the restored version may have usage restrictions depending on the source.