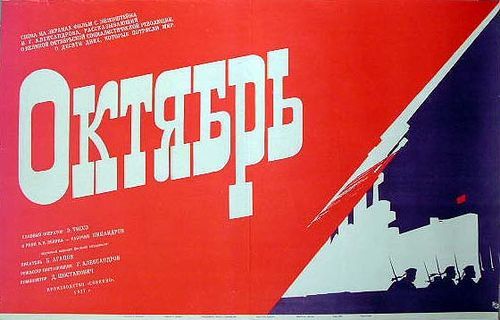

October (Ten Days that Shook the World)

"Ten Days that Shook the World"

Plot

Sergei Eisenstein's epic docu-drama chronicles the pivotal events of the 1917 October Revolution, beginning with the chaos and corruption of the Provisional Government under Kerensky. The film depicts the Bolsheviks' strategic preparations for revolution, including Lenin's return from exile and his passionate speeches calling for uprising. Key historical moments are recreated with dramatic intensity: the storming of the Winter Palace, the seizure of key government buildings, and the declaration of Soviet power. Eisenstein uses thousands of extras and actual locations in Leningrad to create a massive, living tableau of revolution. The culminating scenes show the victorious Bolsheviks establishing their new government, with the film serving as both historical record and revolutionary propaganda celebrating the birth of the Soviet state.

About the Production

The film was commissioned by the Soviet government to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the October Revolution. Eisenstein and his co-director Grigori Aleksandrov used thousands of actual workers, soldiers, and sailors as extras, many of whom had participated in the real revolution. The production faced significant challenges, including recreating historical events with limited resources and dealing with political pressures to portray the revolution according to official party doctrine. The original version underwent extensive revisions after Trotsky's fall from power, with all references to him being removed or altered.

Historical Background

The film was produced during a critical period in Soviet history, marking the tenth anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution while Joseph Stalin was consolidating his power. The late 1920s saw the Soviet Union undergoing rapid industrialization and the implementation of the First Five-Year Plan. Cinema was recognized by the Communist Party as a vital tool for political education and propaganda, with significant state investment in film production. The film's creation coincided with the power struggle between Stalin and Trotsky, which directly impacted the film's content and subsequent editing. This period also saw the flourishing of the Soviet montage theory of filmmaking, with Eisenstein as its leading practitioner. The international context included growing tensions between the Soviet Union and Western powers, making the film's revolutionary message both a domestic celebration and an international political statement.

Why This Film Matters

'October' represents a pinnacle of Soviet montage cinema and remains one of the most influential political films in history. Its innovative editing techniques, particularly the 'intellectual montage' sequences, revolutionized film language and influenced generations of filmmakers worldwide. The film established the template for the historical epic as propaganda, demonstrating how cinema could shape collective memory and political consciousness. Its impact extends beyond cinema to political communication, with its techniques still studied in political science and media studies. The film's visual vocabulary of revolution - masses in motion, flags waving, buildings being stormed - has become archetypal in how revolutions are portrayed in media. Despite its specific political context, the film's formal innovations transcended its propagandistic purpose, influencing everything from Hollywood editing styles to modern music videos and commercials.

Making Of

The production of 'October' was a monumental undertaking that reflected the Soviet Union's commitment to cinema as a tool of political education. Eisenstein and co-director Grigori Aleksandrov spent months researching historical documents and interviewing participants of the actual revolution to ensure authenticity. The filming took place during winter in Leningrad, creating harsh conditions for the cast and crew. The directors employed thousands of actual workers, soldiers, and sailors as extras, bringing authentic revolutionary fervor to the performances. The production faced political interference throughout, particularly regarding the portrayal of Trotsky's role in the revolution. After Trotsky's exile, the filmmakers were forced to re-edit the entire film to remove his presence, creating continuity problems that are still visible in surviving versions. The technical innovations were remarkable for the time, including complex crane shots and the use of multiple cameras to capture large-scale action sequences from different angles simultaneously.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Eduard Tisse and Vasili Khvostov represents some of the most innovative camera work of the silent era. The film employs dynamic camera movement, including dramatic crane shots that sweep over massive crowds of extras. The use of low angles creates heroic proportions for revolutionary figures, while high angles emphasize the power of the masses. Tisse's lighting techniques create stark contrasts between the dark opulence of the Winter Palace and the bright energy of revolutionary crowds. The famous sequence of the machine guns firing on the demonstrators uses rapid cutting and varying camera angles to create a rhythmic, almost musical effect. The cinematography emphasizes geometric compositions and symbolic imagery, with Eisenstein using visual metaphors to convey political ideas. The technical achievements were remarkable for 1927, including complex location shooting and the coordination of multiple cameras for large-scale action sequences.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations that would become standard in cinema. Eisenstein's development of 'intellectual montage' - using the collision of images to create abstract ideas in the viewer's mind - was a revolutionary approach to film editing. The production used multiple cameras simultaneously to capture large-scale action from different angles, allowing for more dynamic editing possibilities. The film's special effects, particularly the sequence showing the machine guns, were groundbreaking for their time. The use of actual locations, including the real Winter Palace, added authenticity that was unusual for historical films of the era. The coordination of thousands of extras in complex choreographed sequences demonstrated new possibilities for crowd control in filmmaking. The film's editing rhythm and pacing influenced the development of action cinema worldwide, with its techniques still studied and emulated today.

Music

As a silent film, 'October' was originally accompanied by live musical performances that varied by theater and location. The score typically included revolutionary songs, classical pieces, and original compositions. In 1966, Dmitri Shostakovich composed an orchestral score specifically for the film, which has become the most recognized musical accompaniment. Shostakovich's score incorporates themes from his earlier works and uses orchestral techniques that mirror Eisenstein's visual montage style. Modern restorations have used various approaches to music, including the Shostakovich score, period-appropriate compiled scores, and new compositions by contemporary musicians. The rhythmic quality of Eisenstein's editing suggests a musical approach to montage, and the film's visual rhythms often create their own kind of silent music through the pace and pattern of cuts.

Famous Quotes

'The revolution is not a dinner party!' - attributed to Lenin in the film

'History will not forgive us if we hesitate!' - revolutionary slogan repeated throughout

'All power to the Soviets!' - the rallying cry of the Bolsheviks

'The Provisional Government has betrayed the revolution!' - from the film's opening intertitles

'Comrades! The time has come!' - Lenin's call to action

Memorable Scenes

- The storming of the Winter Palace - a massive, choreographed sequence with thousands of extras recreating the pivotal moment of the revolution

- The machine guns sequence - Eisenstein's famous montage showing the Provisional Government's forces firing on demonstrators

- The bridge raising scene - symbolic of cutting off the old regime

- Lenin's return to Russia - dramatic entrance of the revolutionary leader

- The Provisional Government's collapse - rapid cutting showing the fall of the old order

- The declaration of Soviet power - the triumphant conclusion with the new government taking control

Did You Know?

- The film was commissioned specifically to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution

- All references to Leon Trotsky were removed from the film after his political downfall, requiring extensive reshoots and editing

- The title comes from John Reed's book 'Ten Days That Shook the World,' which Eisenstein used as inspiration

- The film used over 5,000 extras, many of whom were actual participants in the 1917 revolution

- The famous 'bridge raising' sequence was filmed using actual drawbridges in Leningrad

- Eisenstein's innovative 'intellectual montage' technique was fully developed in this film

- The original version was significantly longer, with about 30 minutes cut for political reasons

- The storming of the Winter Palace sequence took weeks to film and involved complex choreography

- The film was initially banned in several countries, including the United States and United Kingdom

- Many of the costumes and props were authentic items from the 1917 period

What Critics Said

Upon its release, 'October' received mixed reviews from Soviet critics, some of whom felt it was too abstract and intellectual for mass audiences. Western critics were divided, with many praising its technical brilliance while criticizing its overt propaganda. Over time, critical opinion has shifted dramatically, with the film now widely regarded as a masterpiece of world cinema. Film scholars celebrate its groundbreaking editing techniques and its influence on film language. The Criterion Collection release and various restorations have introduced the film to new generations of critics and audiences, leading to reevaluation of its artistic merits beyond its political content. Contemporary critics often note the film's complex relationship to history, acknowledging both its propagandistic purpose and its artistic achievements in creating a mythic vision of revolution.

What Audiences Thought

Initial Soviet audience reception was lukewarm, with many finding the film's complex montage sequences difficult to follow. The working-class audiences for whom it was intended often preferred more straightforward narratives. However, the film was screened extensively at Party meetings, revolutionary commemorations, and in workers' clubs, ensuring it reached its target demographic despite mixed popular response. International audiences were limited due to political restrictions, but where it was shown, it often provoked strong reactions - either admiration for its technical achievements or criticism for its political message. Modern audiences, particularly film students and cinephiles, generally appreciate the film for its historical importance and formal innovations, though its silent era pacing and propagandistic elements can be challenging for contemporary viewers accustomed to different storytelling conventions.

Awards & Recognition

- Honored as a masterpiece of Soviet cinema by the State Film Committee

- Recognized at the 1958 Brussels World's Fair as one of the 12 greatest films of all time

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Battleship Potemkin (1925) - Eisenstein's own earlier work

- The Birth of a Nation (1915) - for its scale and historical ambition

- John Reed's 'Ten Days That Shook the World' - literary source

- D.W. Griffith's editing techniques

- Soviet avant-garde art and theater

- Marxist historical theory

This Film Influenced

- Alexander Nevsky (1938) - Eisenstein's own later work

- The Battleship Potemkin (1925) - shared techniques

- Strike (1925) - Eisenstein's revolutionary trilogy

- Viva Zapata! (1952) - for its revolutionary themes

- The Battle of Algiers (1966) - for its documentary-style approach to revolution

- Reds (1981) - for its portrayal of revolutionaries

- Che (2008) - for its epic scale and political content

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved through multiple restorations, with the most complete versions maintained in Russian state archives. The original negative suffered damage over the years, particularly in sequences that were politically sensitive. Major restorations were undertaken in the 1960s, 1970s, and 2000s. The Criterion Collection released a digitally restored version in 2001, compiled from the best available elements. Some lost footage remains missing, particularly scenes involving Trotsky that were cut for political reasons. The film is considered well-preserved compared to many silent era works, though no complete original version exists. Various archives hold different versions with varying running times and content.