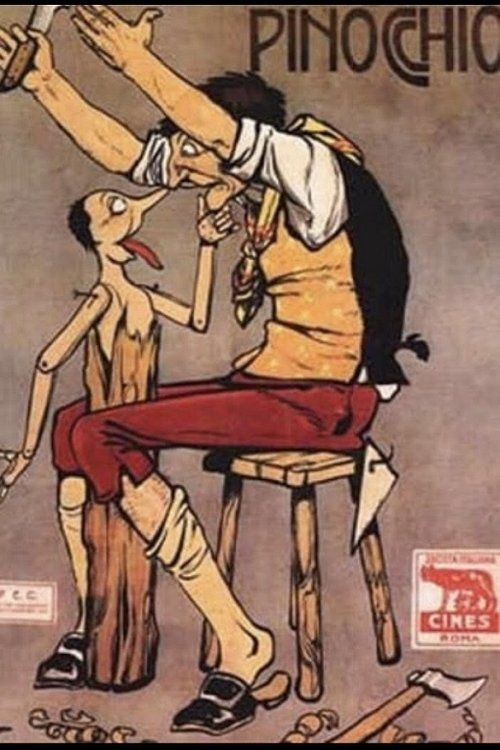

Pinocchio

Plot

In this early Italian silent adaptation of Carlo Collodi's beloved tale, the kind and lonely carpenter Geppetto carves a wooden puppet that miraculously comes to life, naming him Pinocchio. Almost immediately after his creation, Pinocchio runs away from home, embarking on a series of misadventures that test his character and morality. The puppet encounters various temptations and dangerous situations, including meeting the cunning Fox and Cat who deceive him, and the terrifying puppeteer who threatens to turn him into firewood. Throughout his journey, Pinocchio learns valuable lessons about honesty, obedience, and the consequences of his actions, all while being guided by the wise Blue Fairy who offers him a chance to become a real boy. The film follows the classic narrative structure of Pinocchio's transformation from a mischievous wooden puppet to a child who understands the meaning of love, sacrifice, and truthfulness.

Director

Giulio AntamoroAbout the Production

This was one of the earliest feature film adaptations of Carlo Collodi's 1883 novel 'The Adventures of Pinocchio.' The film was produced during the golden age of Italian cinema, when the country was producing elaborate historical epics and literary adaptations. As a silent film, it relied heavily on visual storytelling, exaggerated acting, and intertitles to convey the narrative. The production utilized the primitive special effects techniques of the era, including stop-motion animation for some of Pinocchio's movements and elaborate stage sets to create the fantasy world.

Historical Background

The 1911 production of Pinocchio occurred during what many film historians consider the golden age of Italian cinema. Italy was one of the leading film-producing countries in the world at this time, competing with France and the United States for international markets. The period saw the emergence of feature-length films, with Italian studios producing elaborate historical epics like 'Cabiria' (1914) and literary adaptations that showcased the country's cultural heritage. This Pinocchio adaptation was part of a broader trend of bringing classic literature to the screen, demonstrating cinema's growing cultural legitimacy. The film was made just three years before World War I would dramatically reshape European cinema, disrupting production and distribution networks. The early 1910s also saw significant technical innovations in filmmaking, with longer narratives becoming possible and visual effects becoming more sophisticated. This production represents the ambitions of Italian filmmakers to create works that could compete internationally while celebrating Italian literary culture.

Why This Film Matters

This 1911 adaptation of Pinocchio holds significant cultural importance as one of the earliest cinematic interpretations of a work that would become a cornerstone of children's literature worldwide. The film helped establish the visual language for adapting Pinocchio to screen, influencing countless later versions including the iconic Disney adaptation. It represents an important example of early Italian cinema's ambitions to produce quality literary adaptations that could compete internationally. The film's existence demonstrates how quickly cinema embraced classic literature as source material, recognizing the commercial and cultural value of familiar stories. As an Italian production adapting an Italian literary work, it also reflects national pride in cultural exports. The film's darker tone, closer to Collodi's original than many later adaptations, provides insight into early 20th-century attitudes toward children's entertainment, which was often less sanitized than modern versions. Its partial survival and restoration have made it an invaluable document for film historians studying early special effects techniques and the evolution of fantasy cinema.

Making Of

The production of this 1911 Pinocchio was a significant undertaking for Italian cinema of the era. Director Giulio Antamoro was already an established filmmaker in Italy, known for his ability to handle complex productions. The casting of Polidor as Pinocchio was particularly inspired, as his background in physical comedy and acrobatics allowed him to create a convincing puppet-like performance that didn't rely on dialogue. The film's special effects were groundbreaking for their time, utilizing techniques such as multiple exposure and careful editing to create the illusion of a puppet coming to life. The production design was elaborate for 1911, with detailed sets representing Geppetto's workshop, the puppet theater, and other key locations from the story. The film was shot on location in Italy, taking advantage of the country's growing film infrastructure. Despite the technical limitations of the era, the production team managed to create a visually impressive adaptation that captured the fantasy elements of Collodi's story.

Visual Style

The cinematography of this 1911 production utilized the techniques and limitations of early cinema to create a visually compelling fantasy world. The film employed stationary cameras typical of the era, but used creative blocking and movement within the frame to maintain visual interest. The lighting was naturalistic where possible, with studio lighting used to create dramatic effects for magical sequences. The cinematographer made effective use of deep focus to allow complex compositions, particularly in scenes with multiple characters or elaborate set pieces. Special effects were achieved through in-camera techniques including multiple exposure, substitution splices, and careful matte work. The film's visual style emphasized theatricality, with sets designed to be visually striking from the fixed camera positions. Color tinting was likely used in the original release to enhance emotional impact, with blue tones for night scenes and warm tones for domestic settings, though the surviving black and white print makes this difficult to verify. The cinematography successfully created a sense of wonder appropriate to the fantasy elements while maintaining the visual clarity needed for storytelling in the silent era.

Innovations

The 1911 Pinocchio demonstrated several technical achievements that were notable for its time in early cinema. The film's special effects, while primitive by modern standards, were innovative for 1911, particularly in creating the illusion of a puppet coming to life. The production utilized multiple exposure techniques to show Pinocchio's magical transformations and movements that defied normal human motion. Stop-motion photography was likely employed for some sequences to create jerky, puppet-like movements. The film's production design featured elaborate sets that were impressive for the era, including detailed representations of Geppetto's workshop and the puppet theater. The makeup and prosthetics used to create Pinocchio's wooden appearance were sophisticated for their time, requiring daily application that could withstand the heat of studio lights. The film's relatively long runtime of 62 minutes was ambitious for 1911, requiring careful planning of narrative structure and pacing. The surviving footage shows effective use of cross-cutting between parallel storylines, a technique that was still being refined during this period. The production also demonstrated early understanding of continuity editing, maintaining spatial and temporal coherence across scenes.

Music

As a silent film, the 1911 Pinocchio would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The specific musical scores used have not survived, but typical practice for Italian films of this era would have included either a compiled score using popular classical pieces or specially composed music. For a fantasy film like Pinocchio, the musical accompaniment would likely have included whimsical themes for the puppet's adventures, dramatic music for dangerous situations, and tender melodies for emotional moments. The music would have been performed by a small orchestra or, in smaller theaters, a single pianist or organist. Some larger cinemas might have used the Italian practice of providing detailed musical cue sheets to ensure consistent accompaniment. Modern screenings of the restored version typically feature newly composed scores that attempt to recreate the musical style of the early 1910s while appealing to contemporary audiences. The absence of synchronized sound meant that the film relied entirely on visual storytelling and intertitles, making the musical accompaniment crucial for establishing mood and enhancing emotional impact.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, dialogue was conveyed through intertitles rather than spoken quotes. The film would have included key narrative moments such as Pinocchio's promise to the Blue Fairy, Geppetto's prayers for his puppet son, and the Fox and Cat's deceptive schemes, all presented through title cards and visual performance.

Memorable Scenes

- The creation sequence where Geppetto carves Pinocchio and the puppet first comes to life, utilizing early special effects to show the wooden figure moving independently. The scene where Pinocchio first runs away from home, demonstrating his mischievous nature through physical comedy. The terrifying encounter with the puppet master who threatens to use Pinocchio as firewood, showcasing the darker elements of Collodi's original story. The transformation sequence where Pinocchio begins turning into a donkey, achieved through clever makeup and editing techniques. The emotional reunion between Pinocchio and Geppetto, representing the film's moral core about parental love and redemption.

Did You Know?

- This is believed to be the first feature-length film adaptation of Pinocchio, predating the famous 1940 Disney animated version by nearly three decades

- The film was lost for decades before a partial print was discovered and restored by film archivists

- Polidor, who played Pinocchio, was a famous Italian comic actor of the silent era, known for his acrobatic abilities

- The film was produced by Film d'Arte Italiana, one of Italy's most important early production companies

- At 62 minutes, it was considered a feature-length film at a time when most films were much shorter

- The production used innovative techniques for the time, including multiple exposure effects to create magical transformations

- This adaptation stays closer to Collodi's original dark tone than later versions, including some of the more frightening elements

- The film was distributed internationally, helping to establish Italian cinema's reputation for quality productions

- It was one of several literary adaptations produced by Italian studios during this period

- The surviving print is incomplete, with some sequences believed to be permanently lost

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of the 1911 Pinocchio was generally positive, with reviewers praising the film's ambitious scope and technical achievements. Italian film journals of the era noted the impressive special effects and the convincing performance by Polidor in the title role. International critics, particularly in France and the United States where the film was distributed, commented on Italy's growing reputation for quality productions. Modern film historians view the adaptation as an important milestone in cinema history, particularly for its role in establishing visual conventions for fantasy storytelling. Critics have noted how the film maintains much of the darker tone of Collodi's original novel, contrasting with later sanitized versions. The surviving footage, though incomplete, has been praised for its innovative use of early special effects and its influence on subsequent Pinocchio adaptations. Film scholars consider it a significant example of how early cinema approached the challenge of bringing literary fantasy to life using the limited technology available at the time.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception to the 1911 Pinocchio was reportedly strong, particularly in Italy where the story was familiar to viewers of all ages. The film's blend of fantasy, adventure, and moral lessons resonated with early cinema audiences who were still experiencing the novelty of feature-length storytelling. Children and adults alike were reportedly captivated by the visual effects that brought the wooden puppet to life, a technical achievement that impressed viewers accustomed to simpler film tricks. The performance by Polidor, a popular comic actor of the era, likely drew additional audiences who were familiar with his previous work. In international markets, the familiar story helped overcome language barriers, making the film accessible to diverse audiences. While precise box office figures are unavailable, the film's international distribution suggests commercial success that justified the ambitious production. Modern audiences viewing the restored footage often express fascination with the primitive but effective special effects and the film's preservation of Collodi's darker narrative elements.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Adventures of Pinocchio by Carlo Collodi (1883)

- Italian theatrical traditions

- Commedia dell'arte character archetypes

- Early fantasy literature

- Victorian children's stories with moral lessons

This Film Influenced

- Pinocchio (1940 Disney animated version)

- Pinocchio (2002 live-action Italian film)

- Pinocchio (2019 live-action Disney film)

- The Adventures of Pinocchio (1996)

- Pinocchio (1976 TV movie)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The 1911 Pinocchio is considered a partially lost film, with only fragments of the original production surviving. A incomplete print was discovered in film archives and has been partially restored by preservationists. The surviving footage represents roughly 40-50% of the original feature, with some key sequences missing entirely. The film exists in various archives including the Cineteca Italiana and other European film institutions. Restoration efforts have stabilized the surviving footage and created viewing copies for scholarly and public exhibition. The incomplete nature of the surviving material means that some plot points and character developments may be unclear to modern viewers. Despite its incomplete status, the surviving footage remains invaluable for understanding early Italian cinema and the evolution of fantasy filmmaking. The film is listed on several lost film registries, with ongoing efforts to locate any additional footage that might exist in private collections or overlooked archives.