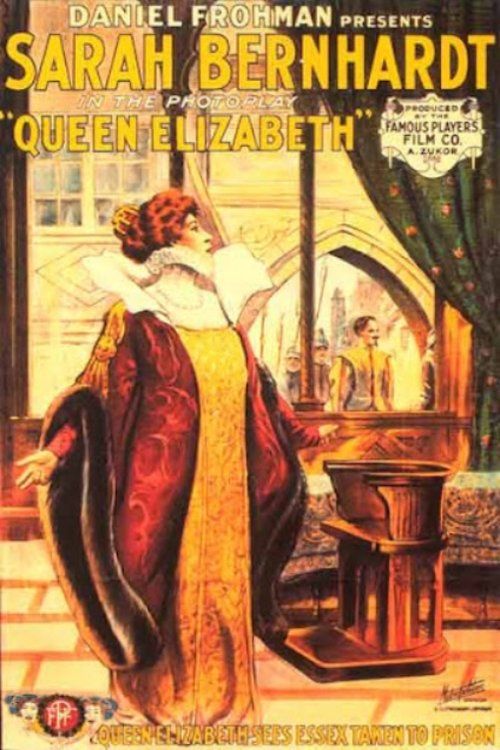

Queen Elizabeth

"The Greatest Tragic Romance of History's Most Powerful Queen"

Plot

The film chronicles the tragic romance between Queen Elizabeth I of England and Robert Devereux, the Earl of Essex, during the final years of Elizabeth's reign. The story begins with Essex returning victorious from his military campaigns in Spain, earning the Queen's favor and becoming her closest confidant and rumored lover. Their relationship deepens despite the significant age difference and Elizabeth's position as monarch, leading to political tensions at court as Essex's ambition grows. When Essex disobeys the Queen's orders and leads an unsuccessful rebellion against her authority, he is captured and sentenced to death. Elizabeth, torn between her duties as queen and her personal feelings, ultimately signs his death warrant, leading to Essex's execution. The film concludes with the aging queen, now alone and isolated, contemplating the sacrifices she has made for her crown and the personal cost of maintaining power.

About the Production

This was a French-American co-production that marked a significant milestone in cinema history as one of the first feature-length films to be imported to the United States. The production spared no expense in recreating the opulence of Elizabeth's court, with authentic period costumes designed by leading Parisian couturiers. Sarah Bernhardt, already in her late 60s, insisted on performing her own stunts and wore heavy prosthetic makeup to appear younger in the early scenes. The film was shot in a matter of weeks but underwent extensive post-production for its time, including hand-tinting of certain scenes for color effects.

Historical Background

The film was produced during a pivotal moment in cinema history when the industry was transitioning from short novelty films to feature-length storytelling. In 1912, films were typically 10-15 minutes long, and the idea of a 45-minute historical drama was revolutionary. The film emerged during the golden age of French cinema, when companies like Pathé and Gaumont dominated global production. It was also a time of intense Franco-American cultural exchange, with American producers looking to European talent to elevate their productions. The choice of Elizabeth I as a subject reflected the era's fascination with historical epics and the growing sophistication of film audiences. The film's production coincided with significant technological advancements in cinematography and film stock, allowing for more sophisticated visual storytelling. Its success came just before World War I would disrupt European film production and shift the industry's center to Hollywood.

Why This Film Matters

Queen Elizabeth represents a crucial turning point in cinema history, marking the transition from short films to feature-length narrative cinema. The film proved that historical subjects could be commercially viable and artistically successful in the new medium, paving the way for the historical epics that would dominate cinema in the coming decades. Its success in the United States demonstrated the international appeal of foreign films and helped establish the feature film as the industry standard. Sarah Bernhardt's involvement lent unprecedented legitimacy to the film medium, attracting theater-goers who had previously dismissed cinema as vulgar entertainment. The film's blend of theatrical grandeur with cinematic intimacy influenced acting styles in early cinema, helping to develop a performance technique suited to the camera rather than the stage. Its commercial success directly led to the formation of what would become Paramount Pictures, one of Hollywood's major studios. The film also established the template for historical romance films that would become a staple of cinema throughout the 20th century.

Making Of

The production was fraught with challenges from the beginning. Sarah Bernhardt, despite her legendary status on stage, was initially reluctant to work in the new medium of film, considering it inferior to theater. She only agreed after being given unprecedented creative control and a record salary. The filming process was difficult for the aging actress, who had to perform under hot studio lights while wearing heavy period costumes and prosthetics. Her relationship with co-star Lou Tellegen, her former lover and much younger man, created tension on set, though their chemistry translated powerfully to the screen. Director Henri Desfontaines had to balance Bernhardt's theatrical style with the more intimate requirements of film acting, resulting in a hybrid performance style that influenced early film acting techniques. The production used innovative lighting techniques to create dramatic shadows and highlights, enhancing the film's emotional impact. Post-production involved extensive hand-tinting of key scenes, particularly the execution sequence, which was colored red for dramatic effect.

Visual Style

The cinematography was considered groundbreaking for its time, utilizing techniques that were innovative in 1912. The film made extensive use of close-ups, particularly for Bernhardt's emotional scenes, which was still a relatively new technique. The lighting design was sophisticated for the period, using dramatic shadows and highlights to enhance the emotional intensity of key scenes. The cinematographer employed moving camera shots during the battle sequences, creating a sense of action and movement that was rare in early cinema. The film also featured carefully composed wide shots to establish the grandeur of Elizabeth's court, contrasting with intimate close-ups during personal moments. Some scenes were hand-tinted, particularly the execution sequence which featured red coloring to heighten the drama. The film's visual style successfully blended theatrical composition with cinematic intimacy, creating a distinctive aesthetic that influenced subsequent historical films.

Innovations

The film featured several technical innovations for its time. It utilized early color tinting techniques, particularly for dramatic effect in the execution scene. The production employed advanced makeup techniques to age and transform the actors, with Bernhardt wearing extensive prosthetics. The film's editing was more sophisticated than typical for 1912, using cross-cutting between parallel actions to build tension. The battle sequences featured innovative camera movements and multiple camera setups, creating a sense of scale and action rarely seen in early cinema. The film also experimented with different film stocks to achieve various visual effects, using faster film for interior scenes and slower stock for exterior shots. The production design included elaborate moving sets and mechanical effects to recreate the grandeur of Elizabeth's court. These technical achievements demonstrated the growing sophistication of film production and helped establish new standards for the industry.

Music

As a silent film, Queen Elizabeth was accompanied by live musical performances during its theatrical runs. The original French premiere featured a specially composed score by French composer Camille Saint-Saëns, though this music is now lost. For American screenings, theaters typically used compiled scores featuring classical pieces that matched the film's dramatic tone. Common musical selections included works by Beethoven, Wagner, and Mendelssohn, chosen to complement the film's tragic romance theme. Theaters often employed full orchestras for the film's exhibition, reflecting its prestige as a major production. Some theaters used cue sheets provided by the distributor to coordinate the music with specific scenes. The execution scene was typically accompanied by dramatic, dissonant music to heighten the tension. The film's success helped establish the practice of using sophisticated musical accompaniment for feature films, a tradition that would continue through the silent era.

Famous Quotes

"The crown sits heavy upon my head, but heavier still upon my heart." - Elizabeth I

"I would trade all of England for one more night with you." - Essex to Elizabeth

"To be a queen is to be forever alone." - Elizabeth I

"Love is the one luxury a queen cannot afford." - Elizabeth I

You have taught me that even the most powerful heart can break." - Essex to Elizabeth" ],

memorableScenes

The emotional confrontation between Elizabeth and Essex after his betrayal, where Bernhardt's performance reaches its dramatic peak as she struggles between her love and her duty as queen,The execution sequence, which was hand-tinted in red and featured innovative cross-cutting between Elizabeth's anguished face and Essex walking to the scaffold,The opening court scene where Essex returns victorious, establishing the grandeur of Elizabeth's court through elaborate sets and hundreds of extras,The intimate scene where Elizabeth removes her royal regalia and speaks to Essex as a woman rather than a queen, showcasing the film's use of close-ups for emotional effect,The final scene with the aging Elizabeth alone in her chambers, contemplating her sacrifices, which demonstrated the potential of film for intimate character studies

preservationStatus

The film is partially preserved with several versions existing in different archives. The original French version is incomplete, with some scenes lost. The American version, which was cut differently, survives in better condition. Portions of the film have been restored by the French Film Archives and the Museum of Modern Art. The film exists in the public domain and has been released on DVD by several companies specializing in classic cinema. Some scenes, including the original color-tinted execution sequence, survive only in fragmentary form. The film's preservation status reflects the challenges of maintaining early cinema, with nitrate decomposition having damaged portions of the original negatives.

whereToWatch

Available on DVD from Kino Lorber Classics as part of their Early Cinema collection,Streaming on The Criterion Channel (periodically featured in their early cinema programming),Available on YouTube in public domain versions (though quality varies),Can be accessed through university film archives and library special collections,Occasionally screened at film festivals specializing in classic cinema,Available through streaming services specializing in silent films such as Fandor

Did You Know?

- This was Sarah Bernhardt's film debut at age 68, despite her being one of the most famous stage actresses in the world

- The film's American success directly led to the founding of Paramount Pictures through Adolph Zukor's Famous Players company

- Bernhardt was paid an unprecedented $25,000 for her role, equivalent to over $700,000 today

- The film was originally titled 'Les Amours de la reine Élisabeth' in French and was later retitled for international markets

- Lou Tellegen, who played Essex, was Bernhardt's real-life lover and former stage partner

- The film was one of the first to use intertitles extensively to explain the historical context to audiences

- A young Cecil B. DeMille was reportedly inspired by this film's success to pursue historical epics

- The film's success proved that feature-length films could be profitable, changing the industry's focus from short films

- Bernhardt insisted on adding scenes not in the original script, including a dramatic death scene for Essex

- The film was screened for royalty across Europe, including a special viewing for King George V

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics were overwhelmingly positive, hailing the film as a masterpiece of the new art form. The New York Times praised Bernhardt's performance as 'sublime' and noted that the film 'elevates the moving picture to the level of high art.' French critics were equally enthusiastic, with Le Figaro calling it 'a triumph of French artistic sensibility.' Modern critics recognize the film as a landmark achievement despite its technical limitations. Film historians consider it a crucial transitional work that bridges theatrical and cinematic traditions. The film's pacing and visual composition are still studied for their innovative use of close-ups and dramatic lighting. While some modern viewers find Bernhardt's acting style overly theatrical, contemporary critics acknowledged that her performance perfectly suited the medium's capabilities in 1912.

What Audiences Thought

The film was a massive commercial success, particularly in the United States where it broke box office records. American audiences, previously accustomed to short comedies and melodramas, were captivated by the film's length and sophisticated storytelling. The film attracted a more upscale audience than typical movies of the era, including many theater-goers who had never before attended a cinema. Audiences were particularly moved by Bernhardt's performance, with many reports of viewers weeping during the execution scenes. The film's success led to increased demand for feature-length films and more sophisticated content. In Europe, audiences were already familiar with Bernhardt's theatrical work, and her film debut was treated as a major cultural event. The film's popularity led to numerous imitations and established the historical romance as a popular genre.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- William Shakespeare's Elizabethan plays

- Victorian historical novels

- French theatrical traditions

- Sarah Bernhardt's stage performances

- Earlier French historical films

This Film Influenced

- The Birth of a Nation (1915)

- Intolerance (1916)

- Cleopatra (1917)

- Joan the Woman (1916)

- The Ten Commandments (1923)