Royal Wedding

"MGM's Great Musical Romance of the Royal Wedding!"

Plot

Tom and Ellen Bowen, a successful brother-sister dance team from the United States, are booked to perform in London during the preparations for the royal wedding of Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip. While in London, Tom becomes smitten with a dancer named Anne Ashmond, while Ellen falls for the wealthy and charming Lord John Brindale. Both siblings must navigate their romantic entanglements while preparing for their big performance, leading to misunderstandings, comedic situations, and ultimately heartfelt resolutions as they discover true love and professional success.

About the Production

The film was conceived as a vehicle to capitalize on the public's fascination with the 1947 royal wedding of Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip, though it was released four years later. The production faced the challenge of creating London settings entirely on MGM soundstages, requiring extensive set construction and matte paintings. The famous ceiling dance sequence required the construction of a custom-built rotating room and camera rig, which took weeks to perfect and cost approximately $50,000 to build.

Historical Background

Royal Wedding was produced during a fascinating transitional period in American cinema and society. Released in 1951, the film emerged during the early Cold War era, when Hollywood was increasingly scrutinized by the House Un-American Activities Committee. The film's celebration of British tradition and monarchy served as a form of cultural diplomacy, reinforcing the 'special relationship' between the United States and United Kingdom during the early Cold War period. The actual royal wedding of Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip in 1947 had been a significant international event, symbolizing hope and renewal after World War II. By 1951, Elizabeth had already become Queen following her father's death, adding an extra layer of timeliness to the film's release. The movie also reflected the changing dynamics of Hollywood musicals, moving away from the backstage formula of the 1930s toward more integrated storytelling and location-inspired narratives, even when those locations were studio creations.

Why This Film Matters

Royal Wedding represents a crucial moment in the evolution of the Hollywood musical genre, bridging the gap between the golden age of 1930s musicals and the more innovative approaches of the 1950s. The film's technical achievements, particularly the ceiling dance sequence, pushed the boundaries of what was possible in musical filmmaking and influenced countless subsequent productions. The movie also exemplifies the post-war American fascination with British culture and tradition, reflecting the strengthening cultural ties between the two nations. Fred Astaire's continued relevance at age 51 challenged Hollywood's ageism and demonstrated the enduring appeal of classic entertainment values. The film's success helped solidify Stanley Donen's reputation as one of Hollywood's premier musical directors, leading to his work on classics like 'Singin' in the Rain' and 'Seven Brides for Seven Brothers.' The song 'Too Late Now' became a jazz standard, recorded by artists ranging from Ella Fitzgerald to Tony Bennett, ensuring the film's cultural legacy extended beyond cinema into the broader musical landscape.

Making Of

The production of 'Royal Wedding' was marked by significant technical innovation and careful planning. The most famous behind-the-scenes challenge was creating the iconic ceiling dance sequence. The special effects team, led by MGM's technical department, constructed a 20-foot diameter cylindrical room that could rotate 360 degrees. The camera was locked in position while the entire room rotated around it, creating the illusion that Astaire was defying gravity. This sequence required Astaire to rehearse for weeks to master dancing on surfaces at impossible angles. The film's choreography was a collaborative effort between Astaire and Hermes Pan, who had been Astaire's longtime choreographic partner since the 1930s. Director Stanley Donen, who had previously co-directed 'On the Town' with Gene Kelly, brought a fresh, energetic approach to the musical numbers, incorporating more dynamic camera movements than typical of the era. The London sets were meticulously recreated using photographs and research, as the production never left California due to budget constraints and Astaire's preference for studio filming.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Royal Wedding, handled by Robert H. Planck and Alfred Gilks, represents some of the most innovative work in musical film photography of its era. The most notable achievement was the ceiling dance sequence, which required the construction of a custom camera rig and rotating set. The cinematographers had to solve the challenge of keeping Astaire in focus while the entire room rotated around a fixed camera position. This involved precise calculations of focal lengths and lighting adjustments to maintain consistent exposure as the set moved through different angles relative to the studio lights. The London street scenes, though filmed on MGM's backlot, employed extensive matte paintings and forced perspective techniques to create convincing urban environments. The film's color palette, captured in Technicolor, emphasized rich, saturated tones that enhanced the glamour of the musical numbers. The dance sequences were photographed with wider lenses than typical for the period, allowing for more dynamic movement within the frame and showcasing the full extent of the choreography.

Innovations

Royal Wedding's most significant technical achievement was undoubtedly the ceiling dance sequence, which represented a breakthrough in special effects and camera work. The production team built a cylindrical room 20 feet in diameter that could rotate 360 degrees, with the camera and furniture bolted to the floor while Astaire danced on what appeared to be the walls and ceiling. This innovation required precise engineering to ensure smooth rotation and safety for the performer. The effect was so convincing that many contemporary viewers believed Astaire had actually defied gravity. The film also employed advanced matte painting techniques to create convincing London street scenes without leaving the studio. The sound recording for the musical numbers utilized MGM's state-of-the-art recording facilities, allowing for clear capture of both vocals and orchestral accompaniment. The Technicolor cinematography pushed the boundaries of color film technology, particularly in capturing the intricate details of costumes and set designs during dance sequences.

Music

The musical score for Royal Wedding was composed by Burton Lane with lyrics by Johnny Mercer, creating one of the most memorable songbooks of the early 1950s MGM musicals. The soundtrack includes the Academy Award-nominated ballad 'Too Late Now,' which became a jazz standard recorded by numerous artists including Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, and Tony Bennett. Other notable songs include the upbeat 'I Left My Hat in Haiti,' the romantic 'You're All the World to Me' (featured in the ceiling dance), and the comic number 'The Happiest Days of My Life.' The musical arrangements were overseen by MGM's legendary musical director Adolph Deutsch, who adapted the songs for both the film's orchestral accompaniment and the dance sequences. The soundtrack successfully blended sophisticated ballroom numbers with more contemporary rhythmic pieces, reflecting the changing musical tastes of early 1950s America. The film's musical numbers were carefully integrated into the narrative, with songs often revealing character motivations or advancing the plot, following the integrated musical model pioneered by shows like 'Oklahoma!' on Broadway.

Famous Quotes

Tom Bowen: 'You're all the world to me, more than you'll ever know.' (sung during the ceiling dance sequence)

Ellen Bowen: 'I'm not going to marry a man just because he's a lord!'

Tom Bowen: 'In this business, you have to be good. And if you're not good, you have to be lucky.'

Ellen Bowen: 'I don't want to be famous. I just want to be happy.'

Tom Bowen: 'Dancing is a vertical expression of a horizontal desire.'

Memorable Scenes

- The iconic ceiling dance sequence where Fred Astaire appears to defy gravity, dancing on the walls and ceiling of his hotel room while singing 'You're All the World to Me'

- The opening number 'Every Night at Seven' featuring Astaire and Powell in a synchronized dance routine establishing their sibling act

- The 'Too Late Now' ballad sequence where Jane Powell sings of her romantic feelings in a beautifully lit, intimate setting

- The 'I Left My Hat in Haiti' number featuring Astaire in a Caribbean-themed dance with exotic costumes and choreography

- The finale with both couples reconciled and performing together in a spectacular Royal Wedding celebration number

Did You Know?

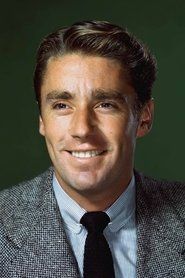

- Fred Astaire was 51 years old during filming, making him one of the oldest leading men in a musical romance at the time.

- The famous 'ceiling dance' sequence was accomplished by building a room inside a cylindrical chamber that could rotate, with the camera and furniture bolted to the floor while Astaire danced on the walls and ceiling.

- Jane Powell was pregnant during filming, which required careful costume design and camera work to conceal her condition.

- The film's story was loosely based on the real-life brother-sister dance team of Fred and Adele Astaire, though their actual career ended decades earlier.

- Peter Lawford was married to Patricia Kennedy, sister of future President John F. Kennedy, during the making of this film.

- The song 'Too Late Now' was nominated for an Academy Award and became a jazz standard recorded by numerous artists.

- This was the first time Fred Astaire and Stanley Donen worked together as director-star, though Donen had previously been Gene Kelly's choreographic partner.

- The film's title was changed several times during production, including 'Wedding Bells' and 'London Wedding,' before settling on 'Royal Wedding.'

- MGM originally considered casting June Allyson opposite Astaire before choosing Jane Powell.

- The film's success led to Astaire and Powell reuniting for 'Deep in My Heart' (1954), though they didn't play romantic leads.

What Critics Said

Upon its release, Royal Wedding received generally positive reviews from critics, who praised Astaire's seemingly ageless talent and the film's technical innovations. The New York Times' Bosley Crowther wrote that 'Mr. Astaire is as nimble and charming as ever' and particularly singled out the ceiling dance as 'a remarkable piece of photographic trickery and athletic grace.' Variety noted that the film 'should prove a highly satisfactory entertainment for all fans of musical films' and praised Jane Powell's 'bright and appealing performance.' Modern critics have reassessed the film as a solid example of the MGM musical at its professional peak, though some find it lacking the artistic ambition of Astaire's earlier collaborations with directors like Rouben Mamoulian or Vincente Minnelli. The ceiling dance sequence continues to be studied and admired as a landmark achievement in special effects and choreography, often cited alongside other groundbreaking musical numbers like Gene Kelly's 'Singin' in the Rain' sequence.

What Audiences Thought

Royal Wedding was a moderate box office success upon its release, earning approximately $2.75 million in North American theaters against a production budget of $1.86 million. While not as financially successful as some of Astaire's earlier films like 'Easter Parade' (1948), it performed well enough to be considered profitable for MGM. Audiences responded enthusiastically to Astaire's magical dance sequences and the film's lighthearted romantic comedy elements. The chemistry between Astaire and Powell, despite their 24-year age difference, was generally well-received by contemporary audiences. The film's timing, capitalizing on continued public interest in the British monarchy following Princess Elizabeth's ascension to the throne, helped attract viewers. Over the decades, Royal Wedding has developed a cult following among classic film enthusiasts and musical fans, who appreciate it as an example of polished Hollywood craftsmanship and a showcase for Astaire's enduring talent. The ceiling dance sequence, in particular, has become one of the most frequently referenced and celebrated moments in Astaire's filmography.

Awards & Recognition

- Academy Award Nominee for Best Music (Original Song) - 'Too Late Now' by Burton Lane and Johnny Mercer

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The real-life career of Fred and Adele Astaire as a brother-sister dance team

- The actual 1947 royal wedding of Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip

- MGM's tradition of lavish musical productions including 'Easter Parade' and 'On the Town'

- The integrated musical structure pioneered by Rodgers and Hammerstein

- British Hollywood films of the 1940s celebrating Anglo-American relations

This Film Influenced

- The Band Wagon (1953) - another Astaire musical with similar themes of artistic integrity

- Silk Stockings (1957) - Astaire's final musical for MGM with comparable production values

- Funny Face (1957) - Astaire musical with international settings and romance

- Later musicals that incorporated innovative camera techniques for dance sequences

- Films that used rotating set technology for special effects, including 2001: A Space Odyssey

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Royal Wedding has been well-preserved by MGM Studios (now owned by Warner Bros.) and exists in its original Technicolor format. The film was restored as part of Warner Bros.' ongoing classic film preservation efforts, with a high-definition transfer created for home video releases. The original negative is stored in the Warner Bros. film archives, and the film has been made available through various home media formats including DVD, Blu-ray, and digital streaming platforms. No significant deterioration has been reported, and the film remains in excellent condition for a production of its era.