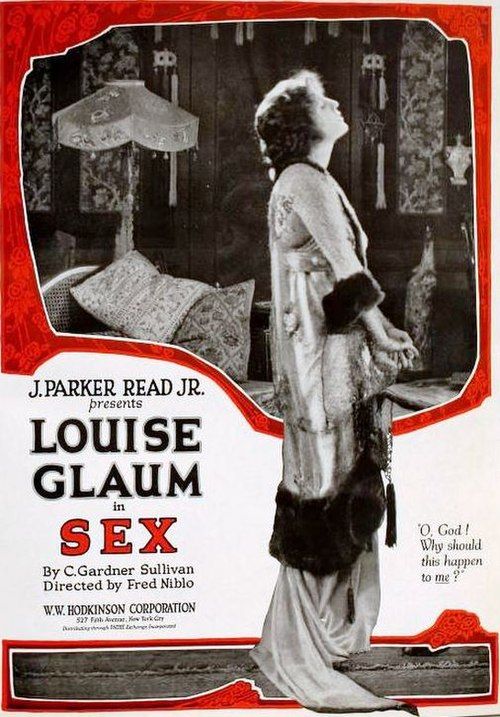

Sex

"The Story of a Woman Who Used Her Sex Appeal as a Weapon"

Plot

Sex (1920) follows the story of Adrienne Renault, a sophisticated Broadway actress who uses her sexual allure as a weapon to manipulate wealthy men. She deliberately targets married men, enjoying the power she holds over them and the thrill of destroying their marriages. When she meets the married millionaire Philip Craig, she successfully seduces him and convinces him to leave his wife and family. However, once Philip has sacrificed everything for her, Adrienne cruelly abandons him for an even wealthier prospect, revealing her true nature as a heartless opportunist. The film concludes with Philip's life in ruins while Adrienne moves on to her next victim, unrepentant and unchanged in her predatory ways. This stark portrayal of female sexuality and moral corruption was considered shocking for its time.

About the Production

The film was made during the early days of Hollywood's moral code enforcement, and its controversial subject matter led to extensive battles with censors. Director Fred Niblo had to fight to keep many scenes intact, and the film was released with numerous cuts in various markets. Louise Glaum's costumes were deliberately designed to be provocative for the time, featuring revealing elements that emphasized her character's seductive nature.

Historical Background

Sex was released during a pivotal moment in American cultural history. The 1920s, known as the Roaring Twenties, was a period of significant social change, with women gaining more independence and challenging traditional moral codes. The film's release came just after World War I, when American society was grappling with changing sexual mores and the emergence of the 'New Woman' who was more sexually liberated and independent. Hollywood itself was transitioning from a loosely regulated industry to one facing increasing pressure from moral reformers and religious groups. The film's controversial nature reflected the broader cultural tensions between traditional Victorian values and the more permissive attitudes emerging in post-war America. This period also saw the rise of consumer culture and the increasing influence of mass media on social norms, with films like Sex playing a role in shaping public discussions about sexuality and morality.

Why This Film Matters

Sex holds an important place in cinema history as one of the earliest American films to explicitly address female sexuality and manipulation. The film's very title was revolutionary for its time, breaking taboos about discussing sex openly in popular entertainment. It contributed to the ongoing debate about cinema's influence on public morality and helped accelerate calls for industry self-regulation. The film's portrayal of a sexually empowered woman who uses her sexuality for personal gain challenged traditional gender roles and reflected changing attitudes about women's place in society. While controversial, the film's commercial success demonstrated that there was an audience for more adult themes in cinema. It also helped establish Louise Glaum as one of the era's most recognizable 'vamp' actresses, a character type that would become a staple of silent cinema. The film's notoriety and the public discussions it generated contributed to the eventual establishment of the Hays Code, which would govern Hollywood content for decades.

Making Of

The production of Sex was fraught with controversy from its inception. The film's studio, J. Parker Read Jr. Productions, was taking a significant risk by producing such a provocative film during a period of increasing moral scrutiny in Hollywood. Louise Glaum, who had built her career playing 'vamp' roles, was perfectly cast as the predatory Adrienne Renault. The film's most challenging scenes involved the seduction sequences, which had to be carefully choreographed to suggest sexual activity without explicitly showing it, due to the emerging censorship standards. The production team used innovative camera angles and lighting techniques to create a sense of intimacy and danger in these scenes. Many local censorship boards demanded cuts before allowing the film to be shown, resulting in different versions being released in different markets. Despite these challenges, the film was completed on schedule and became one of the most talked-about releases of 1920.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Sex was handled by Victor Milner, who would later become one of Hollywood's most respected cinematographers. The film employed innovative lighting techniques to create a moody, atmospheric quality that enhanced its dramatic impact. Milner used chiaroscuro lighting to emphasize the moral ambiguity of the characters and to create visual metaphors for the film's themes of seduction and corruption. The seduction scenes were particularly notable for their use of soft focus and strategic shadows to suggest intimacy without explicitly showing it. The film also made effective use of close-ups to capture the emotional states of the characters, particularly Louise Glaum's expressive face during moments of manipulation and triumph. The cinematography was praised by contemporary reviewers for its artistic quality and its ability to enhance the film's dramatic tension.

Innovations

While Sex was not particularly innovative in terms of technical achievements, it did demonstrate some notable techniques for its time. The film made effective use of double exposure techniques to create dream sequences and moments of psychological revelation. The editing was particularly sophisticated for 1920, using cross-cutting to build tension during seduction scenes and to contrast the different emotional states of characters. The film also employed innovative makeup techniques to enhance Louise Glaum's vamp persona, using cosmetics to create a more exotic and dangerous appearance. The set design was elaborate for its budget, particularly the theater scenes which recreated Broadway environments with impressive detail. The film's technical aspects, while not groundbreaking, were executed with professional polish that elevated the material beyond exploitation fare.

Music

As a silent film, Sex would have been accompanied by live musical performances during its theatrical run. The original score was composed by William Furst, who was one of the most prolific composers of silent film music. The score emphasized dramatic themes during moments of seduction and betrayal, using leitmotifs to represent different characters and their emotional states. During seduction scenes, the music would become more romantic and seductive, while moments of moral reckoning were accompanied by more somber, dramatic themes. The score also incorporated popular songs of the era that would have been familiar to contemporary audiences. Unfortunately, the original score has been lost, as was common with silent film music. Modern screenings of the film, when available, typically feature newly composed scores or period-appropriate music compiled from other sources.

Did You Know?

- The film's provocative title alone caused significant controversy and led to it being banned in several cities across America

- Louise Glaum was one of the highest-paid actresses of the silent era, earning $2,000 per week for this film

- The film was considered so scandalous that it was one of the movies that prompted the creation of the Hays Code in the early 1930s

- Director Fred Niblo married actress Enid Bennett the same year this film was released

- The film was re-released in 1924 under the title 'Sex Madness' to capitalize on its notoriety

- Many theaters refused to display the film's title on their marquees, instead referring to it as 'That Louise Glaum Picture'

- The film was based on a story by playwright and screenwriter C. Gardner Sullivan, who specialized in melodramatic scenarios

- Irving Cummings, who plays the male lead, would later become a prominent director in Hollywood

- The film's success led to several imitations with similarly provocative titles in the early 1920s

- Despite its controversy, the film was praised by some critics for its honest portrayal of sexual manipulation

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception to Sex was deeply divided. Some critics praised the film for its boldness and artistic merit, acknowledging its technical quality and Louise Glaum's powerful performance. The New York Times noted that while the subject matter was controversial, the film was 'well-acted and skillfully directed.' However, many moral critics condemned the film as immoral and dangerous, warning that it would corrupt public morals. Religious publications were particularly harsh in their criticism. Modern film historians view Sex as an important cultural artifact that provides insight into 1920s attitudes toward sexuality and gender. While not considered a masterpiece of silent cinema, it is recognized for its historical significance and for pushing boundaries in film content. The film is often cited in studies of early Hollywood censorship and the evolution of sexual content in American cinema.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception to Sex was largely positive from a commercial standpoint, despite the controversy. The film's scandalous reputation actually increased public interest, and it performed well at the box office in markets where it was allowed to be shown. Many theatergoers were drawn to the film precisely because of its forbidden nature and the promise of seeing risqué content. The film was particularly popular with urban audiences who were more accepting of modern social changes. However, in more conservative areas, the film faced protests and boycotts from moral reform groups. Despite the controversy, or perhaps because of it, the film helped solidify Louise Glaum's status as a major star of the silent era. The film's success demonstrated that there was a market for more adult-themed content, even as it triggered backlash from conservative elements of society.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The vamp character type established by Theda Bara

- European melodramatic traditions

- Victorian morality plays

- Contemporary Broadway plays dealing with sexual themes

This Film Influenced

- The 'vamp' films of the early 1920s

- Later films dealing with female sexuality such as 'Baby Face' (1933)

- Film noir's femme fatale archetype