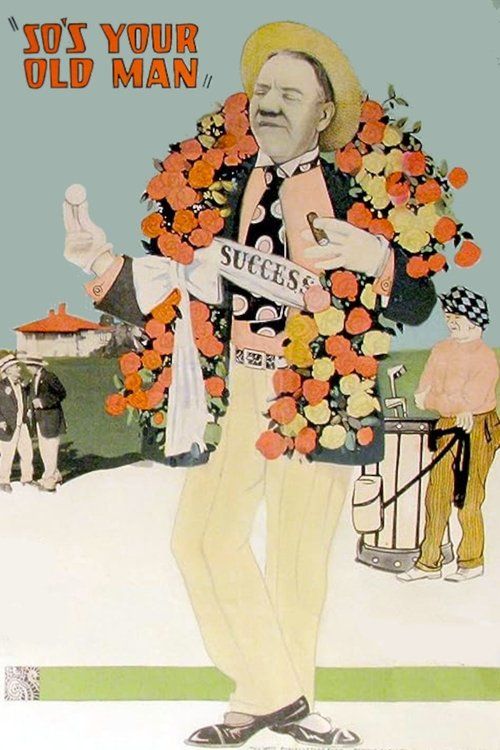

So's Your Old Man

"The Great Comedian in His Greatest Picture!"

Plot

Sam Bisbee, a hen-pecked inventor and perpetual drunk, creates unbreakable glass for automobile windshields but can't seem to get anyone to take him seriously. His social-climbing daughter Pauline is embarrassed by her father's eccentric behavior and lack of success, especially when her wealthy boyfriend Martin's family comes to visit. After Sam's demonstration of his invention goes disastrously wrong, he contemplates suicide but is saved by a princess who recognizes the value of his work. When his invention is finally proven successful after a dramatic accident, Sam becomes wealthy and respected, ultimately winning the approval of his family and society.

About the Production

This was one of W.C. Fields' earliest starring roles in a feature film, showcasing his unique comic persona that would later make him a legend. The film was shot during the transition period of silent cinema, just before the advent of sound. Fields was given considerable creative freedom to improvise many of his comic routines and gags, a practice that would become his trademark throughout his career.

Historical Background

The film was released in 1926, during the peak of the silent film era and just before the revolutionary transition to sound cinema. This was a period of great economic prosperity in America known as the Roaring Twenties, with rapid technological advancement and social change. The automobile was becoming increasingly common, making the film's focus on windshield glass particularly relevant to contemporary audiences. The year 1926 also saw the rise of consumer culture and the American dream of invention and entrepreneurship, themes central to the film's narrative. Hollywood was establishing itself as the global center of film production, with comedy being one of its most popular and successful genres.

Why This Film Matters

So's Your Old Man represents an important early example of W.C. Fields' screen persona that would influence American comedy for decades. The film established the template for the Fields character: the misanthropic but ultimately sympathetic individual battling against societal conventions and family expectations. It also reflects the 1920s fascination with invention and technological progress, while simultaneously satirizing social climbing and pretension. The film's success helped pave the way for Fields to become one of the most distinctive comic voices in American cinema. Its themes of the misunderstood inventor and the triumph of the common man would become recurring elements in American popular culture.

Making Of

The production was marked by W.C. Fields' insistence on improvisation and his reluctance to follow scripts verbatim. Gregory La Cava, understanding Fields' comedic genius, allowed him considerable freedom to ad-lib and modify scenes. The famous unbreakable glass demonstration sequence was largely developed by Fields himself during rehearsals. The production team had to carefully choreograph the various glass-breaking gags to ensure they would be both comic and safe. Fields' drinking habits during filming were legendary, though he maintained he was more professional than his public persona suggested. The film was shot quickly and efficiently by Paramount standards, as the studio was still uncertain about Fields' bankability as a leading man.

Visual Style

The cinematography by James Wong Howe employed the standard techniques of mid-1920s comedy filming, with relatively static camera placement to highlight the performers' physical comedy. Howe, who would become one of Hollywood's most renowned cinematographers, used careful lighting to emphasize Fields' expressive features and comic timing. The glass-breaking sequences required special technical considerations to ensure the gags would read clearly on film. The film's visual style was typical of Paramount productions of the era - clean, professional, and focused on clarity over artistic experimentation. Howe's work showed early signs of the innovative techniques that would later make him famous, particularly in his use of shadows to enhance the comedy's dramatic moments.

Innovations

The film's primary technical achievement was in the execution of the various glass-breaking gags, which required careful preparation and timing. The special effects team developed several techniques for creating the illusion of unbreakable glass that would suddenly shatter. The production also utilized the latest camera and lighting equipment available at Paramount Studios in 1926. While not groundbreaking in technical terms, the film demonstrated solid craftsmanship typical of major studio productions of the era. The film's pacing and editing effectively supported the comedy, with tight cutting during physical comedy sequences.

Music

As a silent film, So's Your Old Man would have been accompanied by live musical performance in theaters. The original cue sheets suggested a mix of popular songs of the era and classical pieces to underscore the action. Comedic moments were typically accompanied by light, playful music, while dramatic scenes used more serious compositions. The score likely included pieces like 'Yes, We Have No Bananas' and other popular 1920s songs to maintain contemporary relevance. The musical accompaniment was crucial to silent comedy, helping to pace the action and emphasize the emotional beats of the story.

Famous Quotes

"If at first you don't succeed, try, try again. Then quit. There's no point in being a damn fool about it." - Sam Bisbee

"I never met a man I didn't like... until I met him." - Sam Bisbee

"A thing worth having is a thing worth cheating for." - Sam Bisbee

Memorable Scenes

- The disastrous unbreakable glass demonstration where Sam's invention spectacularly fails in front of potential investors and his daughter's boyfriend's family

- Sam's contemplation of suicide on a bridge, interrupted by the princess who mistakes him for someone else

- The final scene where Sam's invention is proven successful during a real automobile accident, leading to his vindication and success

Did You Know?

- W.C. Fields' character Sam Bisbee was based on his own vaudeville persona of the inept but lovable drunk

- The film was remade in 1934 as 'You're Telling Me!' with Fields reprising essentially the same role

- Charles 'Buddy' Rogers, who plays the daughter's boyfriend, would later become famous as the male lead in 'Wings' (1927)

- Alice Joyce, who plays Fields' wife, was a major silent film star making a comeback in this film

- Director Gregory La Cava was a former animator who brought a visual flair to his comedy films

- The unbreakable glass demonstration scene became one of Fields' most famous early film routines

- The film's title was a common slang expression of the era, equivalent to saying 'So what?' or 'That's your problem'

- Fields performed his own stunts in the film, including the disastrous glass demonstration sequence

- The princess character who saves Fields was played by Kitty Kelly, who would later become a noted Broadway actress

- This film helped establish the template for Fields' 'everyman vs. society' comedy persona

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised W.C. Fields' performance, noting his unique comic timing and his ability to create sympathy for an essentially flawed character. The New York Times highlighted Fields' 'inimitable style of comedy' and predicted he would become a major star. Variety noted that the film 'provides ample opportunity for Fields to display his peculiar talents as a comedian of the grotesque.' Modern critics view the film as an important early showcase of Fields' developing screen persona, with the Library of Congress noting its significance in the evolution of American screen comedy. The film is now regarded as a valuable document of Fields' work before he became the established icon of his later sound films.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by audiences of 1926, who appreciated W.C. Fields' comic antics and the film's blend of slapstick and situational comedy. Movie theaters reported good attendance, particularly in urban areas where Fields' vaudeville reputation was still known. The film's relatable themes of family dynamics and the desire for recognition resonated with working-class audiences. While not as commercially successful as some of the major comedies of the era featuring Chaplin or Keaton, it performed solidly enough to establish Fields as a viable film star. Audience response was particularly positive to the physical comedy sequences and Fields' underdog triumph at the film's conclusion.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Fields' own vaudeville routines

- The tradition of American slapstick comedy

- Chaplin's tramp character as an underdog figure

- Contemporary films about inventors and innovation

This Film Influenced

- You're Telling Me! (1934) - Fields' remake of this film

- The Bank Dick (1940) - Fields' later film with similar themes

- Never Give a Sucker an Even Break (1941) - Fields' final film

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in complete form and has been preserved by major film archives. A 35mm print exists in the Library of Congress collection. The film has been restored and is available on DVD through various classic film distributors. While not as widely circulated as some of Fields' later work, it is considered to be in good preservation condition for a film of its era.