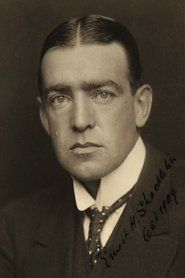

South

"The Greatest Adventure in the History of Exploration"

Plot

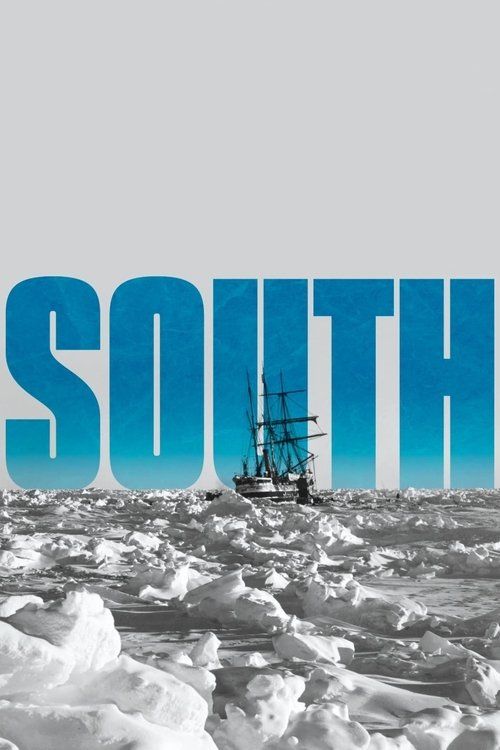

South (1919) is a groundbreaking documentary that chronicles Sir Ernest Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition from 1914-1917. The film captures the harrowing journey of the Endurance as it becomes trapped and ultimately crushed by Antarctic ice, forcing the crew to survive one of history's most remarkable survival stories. Through the lens of expedition photographer Frank Hurley, viewers witness the crew's desperate trek across ice floes, their perilous journey in lifeboats to Elephant Island, and Shackleton's heroic 800-mile voyage to South Georgia for rescue. The documentary showcases unprecedented footage of Antarctic landscapes, wildlife, and the daily struggles of the 28-man crew as they face impossible odds in one of Earth's most hostile environments. The film culminates in the successful rescue of all crew members, making it a testament to human endurance and leadership.

About the Production

Frank Hurley used multiple cameras including a Newman Sinclair and a Paget plate camera. He had to develop film in makeshift darkrooms on the ice and even dove into freezing waters to retrieve some footage when the Endurance was sinking. The original negative was over 25,000 feet long but much was lost due to damage from ice and water.

Historical Background

South was produced in the immediate aftermath of World War I, during a period when the world was hungry for stories of human endurance and survival. The film emerged during the golden age of exploration, when polar expeditions captured the public imagination like space exploration would decades later. The timing was particularly significant as Europe was recovering from the trauma of war, making Shackleton's story of leadership and survival resonate deeply with audiences. The film also represents a crucial moment in documentary filmmaking history, coming just a few years after Robert Flaherty's Nanook of the North and helping establish documentary as a legitimate film genre. The expedition itself (1914-1917) overlapped with World War I, meaning the men were unaware of the global conflict unfolding while they were isolated in Antarctica.

Why This Film Matters

South revolutionized documentary filmmaking by demonstrating that real-life events could be as compelling as fictional narratives. The film established the template for adventure documentaries and influenced generations of filmmakers including Robert Flaherty and later nature documentarians. It preserved one of history's greatest survival stories for posterity, ensuring Shackleton's leadership legacy would endure. The film's visual style and dramatic structure influenced how expedition documentaries would be made for decades. It also helped establish the importance of visual documentation in scientific exploration, leading to photography and cinematography becoming standard equipment on major expeditions. The film's restoration in the 1990s sparked renewed interest in Shackleton and the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, inspiring numerous books, documentaries, and even a IMAX film about the expedition.

Making Of

The production of South was itself as dramatic as the expedition it documented. Frank Hurley, already an experienced photographer, was chosen as the official photographer for the expedition and brought multiple cameras and thousands of feet of film stock. When the Endurance became trapped in ice, Hurley continued filming daily, creating an unprecedented visual record of polar exploration. The most challenging moment came when the ship was crushed by ice pressure - Hurley had to quickly decide what footage to save, ultimately diving into the frigid water multiple times to retrieve film canisters from the sinking vessel. After the crew was stranded on the ice, Hurley continued filming despite extreme conditions, often developing film in makeshift darkrooms carved from ice blocks. The footage he captured of the ship's destruction and the crew's survival was so remarkable that some scenes had to be recreated later in studios to fill gaps in the narrative. Shackleton himself took an active interest in the film's editing, recognizing its historical importance even before the expedition was complete.

Visual Style

Frank Hurley's cinematography in South was groundbreaking for its time, combining technical innovation with artistic vision. He employed multiple camera formats including 35mm film and large-format glass plates, allowing for both motion pictures and still photography. Hurley mastered difficult lighting conditions in the polar environment, using the low angle of the Antarctic sun to create dramatic shadows and textures. His composition of the Endurance trapped in ice has become one of the most iconic images in exploration history. The film features pioneering time-lapse sequences showing the movement of ice and changing weather patterns. Hurley also experimented with early color photography using the Paget color plate process, producing some of the first color images of Antarctica. His camera work during the ship's destruction is particularly remarkable, capturing the violent chaos while maintaining compositional clarity.

Innovations

South represents numerous technical breakthroughs in early documentary filmmaking. Hurley's use of multiple camera formats simultaneously was innovative for the time, allowing both motion pictures and high-quality stills to be captured. The film features some of the earliest successful underwater photography, with Hurley filming beneath the ice to show the ship's hull. The time-lapse sequences showing ice movement and ship destruction were technically revolutionary, requiring precise timing over extended periods. Hurley's development of portable darkroom techniques for processing film in extreme conditions pioneered methods later used by war photographers and documentarians. The film's use of tinting to enhance mood - blue tones for night scenes, amber for daylight - was sophisticated for its era. The preservation of footage under extreme conditions, including keeping film from freezing and protecting it from moisture, demonstrated remarkable technical ingenuity.

Music

The original 1919 release of South was a silent film accompanied by live musical performances. Early screenings featured orchestral scores specifically composed for the film, with music ranging from dramatic classical pieces during dangerous scenes to lighter melodies for moments of hope. The British Film Institute's 1998 restoration commissioned a new score by composer Neil Brand, which has become the standard for modern screenings. Some contemporary screenings feature live improvisation by musicians, continuing the tradition of the film's original presentation. The absence of recorded dialogue in the original version actually enhances the film's universal appeal, allowing the powerful imagery to speak for itself. Modern restorations have carefully preserved the silent film aesthetic while adding subtle sound effects and musical accompaniment that complement rather than overwhelm the visual narrative.

Famous Quotes

"For scientific discovery give me Scott; for speed and efficiency of travel give me Amundsen; but when disaster strikes and all hope is gone, get down on your knees and pray for Shackleton." - Raymond Priestley (often associated with the film's legacy)

"We had seen God in His splendors, heard the text that Nature renders. We had reached the naked soul of man." - Ernest Shackleton (narration in original screenings)

"The ice can do more than any admiral." - Frank Hurley (on film production challenges)

"If you're a leader, a fellow that other fellows look to, you've got to keep going." - Ernest Shackleton

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic sequence showing the Endurance being slowly crushed by ice pressure, with timbers groaning and finally breaking apart

- The haunting shots of the abandoned ship listing in the ice as the crew prepares to leave it forever

- The time-lapse photography of ice movement showing the relentless power of nature

- The perilous journey across ice floes with the crew dragging their lifeboats

- The final rescue scene on South Georgia Island showing the emotional reunion of Shackleton with his men

Did You Know?

- Frank Hurley risked his life repeatedly to get footage, including standing on ice floes as they cracked beneath him

- Some of the most dramatic scenes of the Endurance breaking up were recreated in a studio in England after the original footage was damaged

- Hurley had to choose which film to save when the ship went down - he kept only the best 150 plates and about 3,000 feet of film

- The film was one of the first documentaries to use tinting techniques to enhance the mood of different scenes

- Shackleton himself helped edit the film and provided narration for early screenings

- The original camera equipment weighed over 100 pounds and had to be carried across the ice

- Hurley used early color photography techniques (Paget color plates) for some Antarctic scenes

- The film was shown to King George V and Queen Mary at Buckingham Palace in 1919

- Some footage was shot using a hand-cranked camera while Hurley was suspended in a bosun's chair

- The expedition's survival story remained relatively unknown until the film's restoration in the 1990s brought it new attention

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised South as an extraordinary achievement in both exploration and filmmaking. The Times of London called it 'one of the most remarkable films ever produced' and highlighted Hurley's courage in obtaining the footage. Modern critics have hailed it as a masterpiece of early documentary, with the British Film Institute describing it as 'one of the most important documentary films ever made.' The film is particularly celebrated for its technical achievements under impossible conditions and its raw, unfiltered portrayal of the expedition's hardships. Recent restorations have revealed the sophistication of Hurley's cinematography, with many noting his innovative use of composition and lighting. The film holds a 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on critical reviews, with critics consistently praising its historical importance and artistic merit.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience response was enthusiastic, with the film proving popular in Britain and attracting considerable attention in the United States. Early screenings were often accompanied by live narration, sometimes by expedition members themselves, which added to the immediacy and impact of the experience. Modern audiences who have seen restored versions report being deeply moved by the film's authenticity and the sheer drama of the survival story. The film has developed a cult following among adventure enthusiasts and documentary buffs, with special screenings often selling out. The 1990s restoration introduced the film to new audiences, leading to renewed appreciation for Hurley's work and Shackleton's achievement. Today, the film is frequently shown in museums, film festivals, and educational settings, where it continues to captivate viewers with its raw power and historical significance.

Awards & Recognition

- National Film Preservation Board - National Film Registry selection (2004)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Nanook of the North (1922)

- The Great White Silence (1924)

- With Byrd at the South Pole (1930)

- Early National Geographic documentaries

- Expedition photography of Herbert Ponting

This Film Influenced

- Shackleton (2002 TV miniseries)

- The Endurance: Shackleton's Legendary Antarctic Expedition (2000)

- Antarctica: A Year on Ice (2013)

- March of the Penguins (2005)

- Touching the Void (2003)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been partially preserved and restored by the British Film Institute. The original nitrate negatives suffered significant damage from ice, water, and age, with approximately 60% of the original footage surviving. The BFI completed a major restoration in 1998, combining surviving footage with still photographs and intertitles to recreate the film's narrative. The restored version was selected for the National Film Registry in 2004 for its cultural and historical significance. Some original color footage still exists but has deteriorated significantly. The film remains fragile and requires careful handling for screenings. Digital preservation efforts continue, with high-resolution scans made to ensure the film's survival for future generations.