Steamboat Bill, Jr.

"The Cyclone That Swept the Screen!"

Plot

William 'Steamboat Bill' Canfield Sr. is a rough, no-nonsense steamboat captain on the Mississippi River who eagerly awaits the arrival of his son, whom he hasn't seen since the boy was a baby. Expecting a chip off the old block, Steamboat Bill is horrified when William Jr. arrives as a frail, effete college graduate wearing a ridiculous outfit complete with a ukulele and carrying a parasol. The situation is complicated when William Jr. falls for Kitty King, the daughter of his father's wealthy business rival who owns a modern steamboat and threatens to put Steamboat Bill out of business. As the fathers' rivalry intensifies, a massive cyclone strikes the town, destroying everything in its path and forcing the seemingly weak William Jr. to discover his inner strength and courage to save his father, his love interest, and prove himself as a worthy son.

About the Production

The cyclone sequence required six months of preparation and filming. The production team built an entire town set specifically designed to be destroyed during the storm sequence. Real hurricane-force winds were created using six airplane propellers and wind machines capable of producing 100 mph winds. The famous building facade stunt required precise mathematical calculations and engineering to ensure Keaton's safety while creating maximum visual impact.

Historical Background

1928 was a pivotal year in cinema history, representing the peak of silent filmmaking just as the industry was transitioning to sound. 'Steamboat Bill, Jr.' was released mere months after 'The Jazz Singer' had revolutionized filmmaking with synchronized dialogue and sound. The film captures a transitional moment in American culture, reflecting the tension between traditional values and modernization, embodied in the father-son relationship and the competition between old-fashioned steamboats and modern vessels. The Mississippi River setting evoked nostalgia for a disappearing American way of life as the nation was rapidly urbanizing and modernizing. The film's themes of small business struggles against corporate competition resonated with audiences on the eve of the Great Depression. The cyclone sequence, with its spectacular destruction, can be seen as a metaphor for the upheaval facing both the film industry and American society at large.

Why This Film Matters

'Steamboat Bill, Jr.' represents the zenith of silent comedy and physical filmmaking, showcasing what could be achieved through practical effects and human performance without dialogue or CGI. The film's cyclone sequence, particularly the building facade stunt, has become one of the most iconic moments in cinema history, frequently referenced and parodied in subsequent films and popular culture. The movie influenced generations of comedians and action stars, from Jackie Chan to the Coen Brothers. Its preservation in the National Film Registry recognizes its enduring artistic and cultural importance. The film demonstrates the sophisticated visual storytelling techniques developed during the silent era and serves as a masterclass in physical comedy and stunt work. Modern filmmakers continue to study Keaton's techniques for timing, visual gags, and the integration of spectacular action with comedy.

Making Of

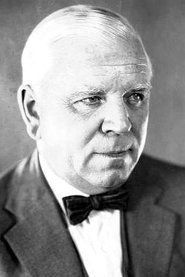

The production of 'Steamboat Bill, Jr.' was one of the most ambitious and expensive of Keaton's career. The cyclone sequence alone required months of planning and engineering. The production team constructed an entire town on the banks of the Sacramento River, complete with buildings designed to collapse in specific ways. The famous wind effects were created using six airplane propellers mounted on trucks, supplemented by wind machines that could generate hurricane-force winds. Keaton insisted on performing his own stunts, including the death-defying building facade sequence where a two-story wall falls around him while he stands perfectly still in the path of an open window. The stunt required precise measurements and marks on the ground for Keaton to hit his exact position. Ernest Torrence, despite being in poor health during filming, delivered a powerful performance as the steamboat captain. The production faced numerous delays due to the complexity of the special effects and the physical toll on the cast and crew. The film's disappointing box office performance, despite its technical brilliance and spectacular sequences, marked the beginning of Keaton's decline as an independent filmmaker.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Devereaux Jennings and Bert Haines was groundbreaking, especially during the cyclone sequence. The camera work captures the chaos and destruction with remarkable clarity and scale, using innovative techniques to film in hurricane conditions. The cinematographers employed multiple cameras to capture the building facade stunt from different angles, ensuring the dangerous moment was preserved on film. The use of long shots establishes the town setting effectively, while close-ups capture Keaton's trademark deadpan reactions. The filming of the cyclone required specially designed camera housings to withstand the wind and water while maintaining clear images. The visual composition throughout the film demonstrates masterful silent-era storytelling, using framing and movement to convey emotion and advance the narrative without dialogue.

Innovations

The film's cyclone sequence represents a monumental technical achievement for its time that remains impressive today. The production team created hurricane-force winds using six airplane propellers mounted on trucks, supplemented by wind machines capable of producing 100 mph winds. The entire town set was constructed with precision engineering to allow for systematic destruction while ensuring the safety of performers. The building facade stunt required mathematical precision and careful engineering to create the illusion of extreme danger while keeping Keaton safe through precise measurements and timing marks. The practical effects, including flying debris, collapsing buildings, and water effects, were all accomplished without modern CGI or safety equipment. The film demonstrated what could be achieved through ingenuity, engineering, and courageous performance.

Music

As a silent film, it was originally accompanied by live musical performances in theaters, typically featuring a theater organ or small orchestra. The musical accompaniment would have included popular songs of the era, classical pieces, and specially composed cues to match the on-screen action. Modern releases feature various reconstructed scores; the Criterion Collection version includes a score by Carl Davis, while other releases feature music by Robert Israel or other silent film composers. The lack of dialogue makes the visual comedy and physical performance even more remarkable, as Keaton had to convey everything through movement and expression alone.

Famous Quotes

Intertitle: 'A college education is a wonderful thing - if you can afford it'

Intertitle: 'My son - a college man! I'm proud of him!'

Intertitle: 'You're the only man in the world I ever loved'

The film's most famous 'quote' is Keaton's deadpan reaction to the building falling around him - no words needed

Intertitle: 'You'll never amount to anything - you're too soft!'

Memorable Scenes

- The building facade fall - Keaton stands unmoved as a two-story building wall falls around him, passing through an open window space in what may be cinema's most famous stunt

- The cyclone sequence - Keaton battling hurricane winds, flying through the air, and performing incredible stunts amid flying debris and collapsing buildings

- Keaton's introduction - arriving in ridiculous college attire with ukulele and parasol, shocking his rough father

- The riverboat race - competing against the rival's modern steamboat in a desperate bid to save the family business

- Keaton hanging from a tree during the flood - another death-defying stunt as he clings to branches while the town is destroyed around him

- The final rescue - saving his father and proving his worth during the devastating storm

- The transformation scene - Keaton changing from his effete college clothes to practical work clothes

Did You Know?

- The iconic building facade stunt was performed by Buster Keaton himself and was incredibly dangerous - if he had been off by just a few inches, he would have been killed

- This was Buster Keaton's last independent film before he signed with MGM and lost creative control over his work

- Ernest Torrence, who played Steamboat Bill Sr., died of pneumonia just three months after the film's release at age 53

- The cyclone sequence cost more to film than most entire movies of the era

- Keaton's character's ridiculous college outfit was based on actual 1920s college fashion trends, particularly the 'Oxford bags' trousers and straw hat

- The film was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry in 2016 for being 'culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant'

- During the cyclone sequence, Keaton performed all his own stunts including hanging from a tree branch and being blown through the air

- The production used over 600 extras during the cyclone sequence

- The wind machines used for the cyclone were so powerful that they could blow cars across the street

- The film's original title was simply 'Steamboat Bill' but was changed to emphasize Keaton's character

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews were mixed to positive, with critics generally praising Keaton's physical comedy and the spectacular cyclone sequence while noting the somewhat conventional romantic plot. The New York Times praised the film's 'thrilling cyclone scenes' and Keaton's 'inimitable' performance. Modern critics universally acclaim the film as one of Keaton's masterpieces. Roger Ebert included it in his Great Movies collection, calling it 'one of the great silent comedies' and praising the cyclone sequence as 'one of the most amazing sequences ever filmed.' The film holds a perfect 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes and is regularly listed among the greatest films ever made by publications like Cahiers du Cinéma and Sight & Sound.

What Audiences Thought

Initial box office performance was disappointing, particularly given the film's substantial budget and the star power of Keaton. The film's release coincided with the public's growing fascination with talkies, which hurt attendance for silent films. However, over the decades, the film has gained a devoted following among film enthusiasts and is now considered a classic of world cinema. Modern audiences continue to be amazed by the physical stunts and Keaton's comedic timing, with the cyclone sequence remaining breathtaking even by today's standards. The film's reputation has grown significantly through home video releases and screenings at film festivals and revival houses.

Awards & Recognition

- Selected for preservation in the National Film Registry (2016)

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs - #58 (2007)

- Sight & Sound's Greatest Films of All Time (multiple critics' polls)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Earlier riverboat films and literature like 'Show Boat'

- Harold Lloyd's daredevil comedy style

- Charlie Chaplin's blend of comedy and pathos

- Traditional American tall tales and folklore

- Contemporary college culture and fashion trends

This Film Influenced

- Jackie Chan's action comedies (particularly his use of dangerous stunts for comedic effect)

- The Coen Brothers' 'O Brother, Where Art Thou?' (river setting and period elements)

- Modern disaster films' practical effects approach

- Physical comedies from Jim Carrey to Rowan Atkinson

- Pixar's 'Up' (house flying sequence)

- Numerous films featuring building collapse stunts

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved by the Library of Congress and selected for the National Film Registry in 2016. Multiple restored versions exist, with the most complete versions running 71 minutes. The film has survived in excellent condition compared to many silent films of the era. The Criterion Collection released a restored 4K version in 2020, making Keaton's masterpiece available in exceptional quality for modern audiences. The preservation efforts ensure that future generations can appreciate this landmark of silent cinema.