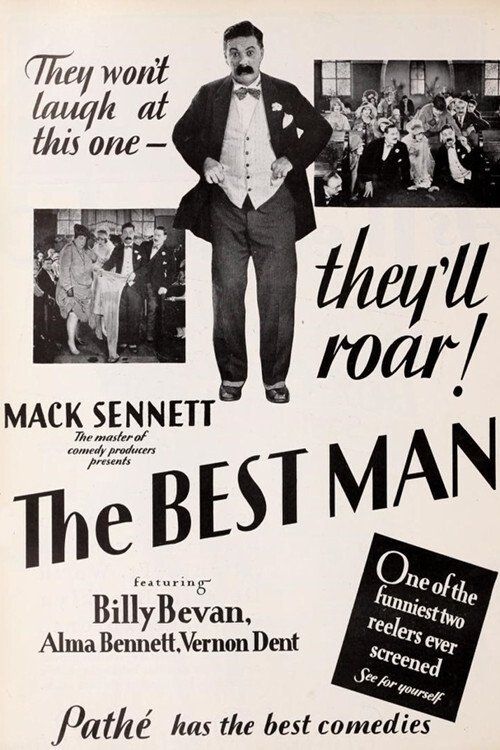

The Best Man

Plot

In this silent comedy short, a bride and groom eagerly await their wedding ceremony, but there's one crucial problem - the best man hasn't arrived. When Billy Bevan's character finally shows up as the best man, he's covered in sticky tar after an unfortunate incident en route to the church. Despite his messy appearance, the groom is relieved that the best man remembered to bring the wedding ring. However, the tar creates a series of escalating disasters throughout the ceremony, from sticking to the bride's dress to causing mishaps with the ring exchange. The chaos continues through the wedding reception and even the honeymoon send-off, threatening to derail the newlyweds' marriage before it truly begins and certainly testing their friendship with their hapless best man.

About the Production

This was one of many comedy shorts produced during the transition from silent to sound films. The film was likely shot quickly on a modest budget, typical of comedy shorts of the era. The tar gags required careful timing and coordination to create the escalating comedy without endangering the actors.

Historical Background

1928 was a pivotal year in cinema history, marking the end of the silent era and the beginning of the sound revolution. The Jazz Singer had been released in October 1927, and studios were scrambling to convert to sound technology. During this transitional period, many silent comedies like The Best Man were still being produced and released, though they were quickly becoming obsolete. The film represents the culmination of silent comedy techniques developed over the previous decade, with its emphasis on visual gags, physical comedy, and situational humor. Mack Sennett's studio, which produced this film, was one of the last bastions of pure silent comedy, though they too would soon have to adapt to the new sound era.

Why This Film Matters

The Best Man represents the final flowering of the silent comedy short format that had dominated early cinema. As a product of Mack Sennett's comedy factory, it embodies the slapstick traditions that would influence comedy for generations. The film's focus on a wedding mishap reflects the common comedic trope of special occasions gone wrong, a formula that would be repeated in countless comedies throughout cinema history. While not as well-known as the works of Chaplin or Keaton, this film is representative of the everyday comedy shorts that entertained audiences in movie theaters during the golden age of silent cinema.

Making Of

The Best Man was produced during a tumultuous period in Hollywood history when studios were rapidly transitioning from silent to sound films. Director Harry Edwards, a veteran of silent comedy, had to work quickly and efficiently to maintain the pace of short film production. The tar sequences required careful choreography and timing, with Billy Bevan having to perform numerous takes to get the physical comedy just right. The sticky tar prop was likely a mixture of molasses and other safe ingredients that could be easily cleaned between takes. The film was shot on a tight schedule typical of comedy shorts of the era, often completing production in just a few days. The church set was probably a studio construction, allowing for multiple camera angles and quick reset between scenes.

Visual Style

The cinematography in The Best Man would have been straightforward and functional, typical of comedy shorts of the era. The camera work would have emphasized clear visibility of the physical gags, particularly the tar-related mishaps. Static shots would have been used for most scenes, with the camera positioned to capture the full range of movement required for the slapstick comedy. The lighting would have been bright and even, ensuring that the sticky tar and its effects were clearly visible to the audience.

Music

As a silent film, The Best Man would have been accompanied by live musical performance in theaters. The score would typically have been provided by a theater organist or small ensemble, using standard musical cues for comedy, romance, and mishap situations. The music would have been synchronized to the action on screen, with lively, upbeat music during the comedic sequences and more romantic themes during the wedding ceremony scenes.

Memorable Scenes

- The best man's arrival covered in tar, causing chaos in the church

- The ring exchange scene where the tar causes the ring to stick and be lost

- The reception scene where the tar continues to cause problems with food and guests

- The honeymoon send-off where the best man's tar-covered presence creates final embarrassment

Did You Know?

- This was one of the final silent comedies before the full transition to sound films in Hollywood

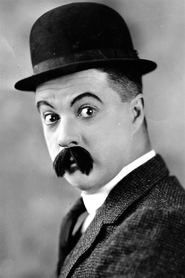

- Billy Bevan was one of Mack Sennett's most reliable comedy stars, known for his expressive face and physical comedy skills

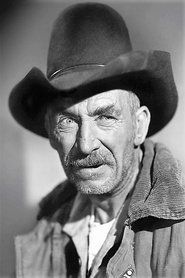

- Vernon Dent, who plays a supporting role, would later become famous for his work with The Three Stooges in their comedy shorts

- Director Harry Edwards was a prolific comedy short director, helming over 200 films during his career

- The tar gags were a classic silent comedy trope, using sticky substances to create visual humor and physical predicaments

- Alma Bennett was a popular actress of the 1920s who appeared in over 60 films before retiring from acting

- The film was released just months before The Jazz Singer revolutionized cinema with synchronized dialogue

- Mack Sennett, whose studio produced this film, was known as 'The King of Comedy' for pioneering slapstick comedy in early cinema

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews of The Best Man were likely modest, as comedy shorts were generally considered filler programming between feature films. The film would have been reviewed primarily in trade publications like Variety and The Moving Picture World, where critics would have noted Billy Bevan's reliable comic performance and the effectiveness of the tar gags. Modern critical assessment of the film is limited due to its status as a relatively obscure short, though film historians recognize it as a typical example of late silent comedy production values and humor.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1928 would have enjoyed The Best Man as light entertainment before or between feature presentations. The visual humor and physical comedy were universally understood and didn't require the sophistication of more artistic silent films. Wedding-themed comedies were popular with audiences of the era, as they presented relatable situations exaggerated for comic effect. The film's reception would have been positive but not remarkable, typical of the hundreds of comedy shorts produced during this period.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Mack Sennett comedies

- Charlie Chaplin shorts

- Buster Keaton films

- Harold Lloyd comedies

This Film Influenced

- Three Stooges shorts

- Abbott and Costello films

- Wedding comedy films

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of The Best Man (1928) is uncertain. Many silent shorts from this era have been lost due to the unstable nature of nitrate film and lack of preservation efforts in early Hollywood. Some Mack Sennett comedies have survived in archives or private collections, but specific information about this title's survival is not readily available.