The Cheat

"A Story of the White Slave Traffic! A Sensational Drama of Modern Life!"

Plot

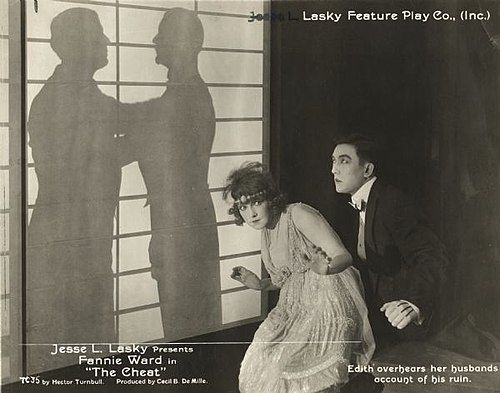

Edith Hardy, a spoiled and materialistic socialite married to wealthy stockbroker Richard Hardy, impulsively embezzles $10,000 from the Red Cross charity fund she chairs to invest in the stock market, hoping to double her money for personal luxuries. When her investment fails disastrously, she faces exposure and ruin, desperately turning to her exotic acquaintance, the wealthy and predatory Burmese ivory dealer Tori, for a loan. Tori agrees to help her but demands sexual favors as collateral, branding her with his personal seal as a mark of ownership when she cannot repay him. When Edith's husband discovers the missing money and suspects infidelity, Tori attempts to blackmail her into becoming his mistress completely. The film culminates in a violent confrontation where Richard shoots Tori, leading to a dramatic trial where Edith confesses everything, ultimately resulting in her redemption and Tori's death.

About the Production

The film was shot in just 15 days with a budget of $12,000. DeMille insisted on using real ivory for Tori's collection, importing authentic pieces to create an authentic atmosphere. The controversial branding scene was achieved using a heated iron prop that left a temporary mark on Fannie Ward's shoulder. The film's success led to DeMille's contract being renewed and his salary increased significantly.

Historical Background

The Cheat was released during a period of significant social change in America, as the Progressive Era's moral reforms clashed with modernization and changing sexual mores. The film reflected contemporary anxieties about immigration, particularly Asian immigration, and the perceived threat to white American virtue. 1915 was also the year of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, which featured 'human zoos' and exoticized displays of Asian cultures, reinforcing the stereotypes the film both reflected and perpetuated. The film's treatment of female sexuality and financial independence spoke to the growing 'New Woman' phenomenon, while its moral punishment of transgression aligned with Progressive Era concerns about urban corruption and moral decay.

Why This Film Matters

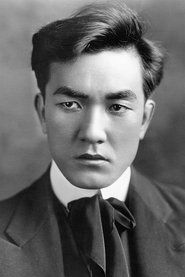

The Cheat represents a pivotal moment in American cinema history, establishing the template for the exotic villain trope and demonstrating film's power to address taboo subjects. It launched Sessue Hayakawa as the first Asian American movie star, creating both opportunities and typecasting for Asian actors in Hollywood. The film's success proved that audiences would accept complex, morally ambiguous characters and controversial themes in cinema. Its visual style, particularly DeMille's use of lighting and shadow to create psychological depth, influenced the development of film noir decades later. The film also exemplifies early Hollywood's approach to race and sexuality, simultaneously progressive in casting an Asian actor in a leading role while reinforcing harmful stereotypes that would persist for generations.

Making Of

Cecil B. DeMille pushed the boundaries of what was acceptable in cinema with this film, incorporating themes of sexual slavery, interracial desire, and moral corruption. The casting of Sessue Hayakawa as the predatory Asian villain was both groundbreaking and problematic, as it created stereotypes that would persist in Hollywood for decades. Fannie Ward, who was married to Jack Dean (her co-star in the film), insisted on having her husband cast as her on-screen husband to avoid any real-life complications. The film's most controversial scene, where Tori brands Edith with a hot iron, was filmed with Ward actually being marked with a heated prop, causing genuine pain and discomfort. DeMille used innovative lighting techniques, particularly in the scenes with Hayakawa, creating shadows and contrasts that emphasized his character's exotic and dangerous nature. The production faced censorship challenges from multiple state boards, requiring several cuts and re-edits before it could be widely distributed.

Visual Style

The film featured innovative cinematography by Alvin Wyckoff, who employed dramatic lighting techniques that would later be associated with film noir. DeMille used chiaroscuro lighting to create psychological depth, particularly in scenes with Hayakawa's character, using shadows to emphasize his mysterious and dangerous nature. The film also featured sophisticated camera movements for its time, including tracking shots during the chase sequences. The branding scene used close-ups to maximize emotional impact, a technique still relatively new in 1915. The cinematography helped establish the visual language of melodrama that would define Hollywood cinema for decades.

Innovations

The Cheat pioneered several technical innovations that would become standard in filmmaking. DeMille's use of dramatic lighting to create psychological atmosphere was groundbreaking for its time. The film employed sophisticated editing techniques, including cross-cutting between parallel actions to build tension. The makeup effects used for the branding scene were particularly advanced, creating a realistic wound that shocked audiences. The film's set design, particularly Tori's exotic apartment filled with authentic ivory and Asian artifacts, set new standards for visual storytelling. DeMille also experimented with camera angles and movements that enhanced the psychological intensity of key scenes.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Cheat' was accompanied by live musical scores during its theatrical run. The original cue sheet suggested specific musical pieces for different scenes, including classical compositions by composers like Wagner and Tchaikovsky for dramatic moments. Modern restorations have been scored by contemporary silent film composers, including Robert Israel and Rodney Sauer, who have created new orchestral arrangements that capture the film's intense emotional tone. The original theatrical experience would have varied by theater, with larger venues employing full orchestras while smaller theaters used piano or organ accompaniment.

Famous Quotes

Tori: 'In my country, when a woman owes a man money, she pays with her body.'

Edith: 'I would rather die than be your slave!'

Tori: 'You belong to me now. I have marked you as mine.'

Richard: 'I would kill any man who dared to touch my wife!'

Memorable Scenes

- The shocking branding scene where Tori uses a hot iron to mark Edith's shoulder as his property, considered one of the most controversial moments in early cinema

- The tense confrontation in Tori's exotic apartment, filled with ivory treasures and shadows, where Edith desperately begs for the loan

- The dramatic courtroom scene where Edith confesses her crimes, leading to her moral redemption

- The climactic shooting where Richard confronts Tori, resulting in the villain's death

- The opening scenes showcasing Edith's luxurious lifestyle and materialistic desires

Did You Know?

- The film was so controversial that it was banned in several cities and states for its interracial themes and implied sexual content.

- Sessue Hayakawa became the first Asian American movie star and one of the highest-paid actors of the era, earning $5,000 per week after this film.

- The branding scene with the hot iron was considered so shocking that some theaters refused to show the film or demanded cuts.

- Fannie Ward was 41 years old during filming but played a character meant to be in her 20s, requiring extensive makeup and camera techniques.

- The film was remade three times: in 1923 with Pola Negri, in 1931 with Tallulah Bankhead, and in 1937 as 'Dangerous Love' with Anna May Wong.

- Cecil B. DeMille considered this one of his most important early films and used it to establish his reputation for sensational storytelling.

- The original script was much longer, but DeMille cut it down to create a faster-paced, more intense narrative.

- Hayakawa's character was originally written as a Japanese character but was changed to Burmese to avoid political tensions with Japan.

- The film's success led to a wave of 'exotic villain' films featuring Asian actors in antagonist roles.

- Despite the controversial themes, the film was praised by critics for its technical innovation and powerful performances.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics were divided but generally impressed by the film's technical innovation and powerful performances. The New York Times praised it as 'a masterpiece of cinematic art' while warning about its 'dangerous themes.' Modern critics recognize the film as a groundbreaking work despite its problematic racial politics. Film scholar Kevin Brownlow called it 'one of the most important films of the silent era' for its technical achievements and narrative sophistication. The film is now studied in cinema courses as an example of early Hollywood's treatment of race, sexuality, and morality.

What Audiences Thought

The Cheat was a tremendous box office success, earning approximately eight times its production cost and becoming one of the biggest hits of 1915. Audiences were shocked and fascinated by its controversial content, with many theaters reporting sold-out shows and repeat viewings. The film's notoriety actually increased its popularity, with word-of-mouth spreading about its scandalous scenes. Despite censorship in some markets, audiences found ways to see the complete version, making it one of the first films to benefit from being 'banned in Boston.' The film made Sessue Hayakawa a matinee idol, particularly among female audiences who were drawn to his intense, sensual performance.

Awards & Recognition

- Named one of the '100 Greatest American Films' by the American Film Institute in 2007

- Selected for preservation in the National Film Registry in 1993

Film Connections

Influenced By

- D.W. Griffith's 'The Birth of a Nation' (1915) for controversial content

- European melodramas for emotional intensity

- Victorian literature for moral themes

- Contemporary newspaper scandals for plot inspiration

This Film Influenced

- 'Shanghai Express' (1932)

- 'The Mask of Fu Manchu' (1932)

- 'The Letter' (1940)

- 'Sayonara' (1957)

- Film noir visual style

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved by the Library of Congress and was selected for the National Film Registry in 1993. A complete 35mm print exists in the George Eastman Museum collection. The film has been restored multiple times, with the most recent restoration completed in 2014 by the Museum of Modern Art. Some scenes remain missing or damaged, but the narrative is essentially complete. The film is considered one of the best-preserved features of its era.